1.

Introduction

Hopfield neural networks have recently sparked significant interest, due to their versatile applications in various domains including associative memory [1], image restoration [2], and pattern recognition [3]. In neural networks, time delays often arise due to the restricted switching speed of amplifiers [4]. Additionally, when examining long-term dynamic behavior, nonautonomous characteristics become apparent, with system coefficients evolving over time [5]. Moreover, in biological nervous systems, synaptic transmission introduces stochastic perturbations, adding an element of randomness [6]. As we know that time delays, nonautonomous behavior, and stochastic perturbations can induce oscillations and instability in neural networks. Hence, it becomes imperative to investigate the stability of stochastic delay Hopfield neural networks (SDHNNs) with variable coefficients.

The Lyapunov technique stands out as a powerful approach for examining the stability of SDHNNs. Wang et al. [7,8] and Chen et al. [9] employed the Lyapunov-Krasovskii functional to investigate the (global) asymptotic stability of SHNNs characterized by constant coefficients and bounded delay, respectively. Zhou and Wan [10] and Hu et al. [11] utilized the Lyapunov technique and some analysis techniques to investigate the stability of SHNNs with constant coefficients and bounded delay, respectively. Liu and Deng [12] used the vector Lyapunov function to investigate the stability of SHNNs with bounded variable coefficients and bounded delay. It is important to note that establishing a suitable Lyapunov function or functional can pose significant challenges, especially when dealing with infinite delay nonautonomous stochastic systems.

Meanwhile, the fixed point technique presents itself as another potent tool for stability analysis, offering the advantage of not necessitating the construction of a Lyapunov function or functional. Luo used this technique to consider the stability of several stochastic delay systems in earlier research [13,14,15]. More recently, Chen et al. [16] and Song et al. [17] explored the stability of SDNNs characterized by constant coefficients and bounded variable coefficients using the fixed point technique, yielding intriguing results. However, the fixed point technique has a limitation in the stability analysis of stochastic systems, stemming from the inappropriate application of the Hölder inequality.

Furthermore, integral or differential inequalities are also powerful techniques for stability analysis. Hou et al. [18], and Zhao and Wu [19] used the differential inequalities to consider stability of NNs, Wan and Sun [20], Sun and Cao [21], as well as Li and Deng [22] harnessed variation parameters and integral inequalities to explore the exponential stability of various SDHNNs with constant coefficients. In a similar vein, Ruan et al. [23] and Zhang et al. [24] utilized integral and differential inequalities to probe the pth moment exponential stability of SDHNNs characterized by bounded variable coefficients.

It is worth highlighting that the literature mentioned previously exclusively focused on investigating the exponential stability of SDHNNs, without addressing other decay modes. Generalized exponential stability was introduced in [25] for cellular neural networks without stochastic perturbations, and is a more general concept of stability which contains the usual exponential stability, polynomial stability, and logarithmical stability. It provides some new insights into the stability of dynamic systems. Motivated by the above discussion, we are prompted to explore the pth moment generalized exponential stability of SHNNs characterized by variable coefficients and infinite delay.

It is important to note that the models presented in [20,21,25,26,27,28] are specific instances of system (1.1). System (1.1) incorporates several complex factors, including unbounded time-varying coefficients and infinite delay functions. As a result, discussing the stability and its decay rate for (1.1) becomes more complicated and challenging.

The contributions of this paper can be summarized as follows: (ⅰ) A new concept of stability is utilized for SDHNNs, namely the generalized exponential stability in pth moment. (ⅱ) We establish a set of multidimensional integral inequalities that encompass unbounded variable coefficients and infinite delay, which extends the works in [23]. (ⅲ) Leveraging these derived inequalities, we delve into the pth moment generalized exponential stability of SDHNNs with variable coefficients, and the work in [10,11,20,21,26,27] are improved and extended.

The structure of the paper is as follows: Section 2 covers preliminaries and provides a model description. In Section 3, we present the primary inequalities along with their corresponding proofs. Section 4 is dedicated to the application of these derived inequalities in assessing the pth moment generalized exponential stability of SDHNNs with variable coefficients. In Section 5, we present three simulation examples that effectively illustrate the practical applicability of the main results. Finally, Section 6 concludes our paper.

2.

Preliminaries and model description

Let Nn={1,2,...,n}. |⋅| is the norm of Rn. For any sets A and B, A−B:={x|x∈A, x∉B}. For two matrixes C,D∈Rn×m, C≥D, C≤D, and C<D mean that every pair of corresponding parameters of C and D satisfy inequalities ≥, ≤, and <, respectively. ET and E−1 represent the transpose and inverse of the matrix E, respectively. The space of bounded continuous Rn-valued functions is denoted by BC:=BC((−∞,t0];Rn), for φ∈BC, and its norm is given by

(Ω,F,{Ft}t≥t0,P) stands for the complete probability space with a right continuous normal filtration {Ft}t≥t0 and Ft0 contains all P-null sets. For p>0, let LpFt((−∞,t0];Rn):=LpFt be the space of {Ft}-measurable stochastic processes ϕ={ϕ(θ):θ∈(−∞,t0]} which take value in BC satisfying

where E represents the expectation operator.

In system (1.1), zi(t) represents the ith neural state at time t; ci(t) is the self-feedback connection weight at time t; aij(t) and bij(t) denote the connection weight at time t of the jth unit on the ith unit; fj and gj represent the activation functions; σij(t,zj(t),zj(t−δij(t))) stands for the stochastic effect, and δij(t)≥0 denotes the delay function. Moreover, {ωj(t)}j∈Nn is a set of Wiener processes mutually independent on the space (Ω,F,{Ft}t≥0,P); zi(t,ϕ) (i∈Nn) represents the solution of (1.1) with an initial condition ϕ=(ϕ1,ϕ2,...,ϕn)∈LpFt, sometimes written as zi(t) for short. Now, we introduce the definition of generalized exponentially stable in pth (p≥2) moment.

Definition 2.1. System (1.1) is pth (p≥2) moment generalized exponentially stable, if for any ϕ∈LpFt, there are κ>0 and c(u)≥0 such that limt→+∞∫tt0c(u)du→+∞ and

where −∫tt0c(u)du is the general decay rate.

Remark 2.1. Lu et al. [25] proposed the generalized exponential stability for neural networks without stochastic perturbations, we extend it to the SDHNNs.

Remark 2.2. We replace ∫tt0c(u)du by λ(t−t0), λln(t−t0+1), and λln(ln(t−t0+e)) (λ>0), respectively. Then (1.1) is exponentially, polynomially, and logarithmically stable in pth moment, respectively.

Lemma 2.1. [29] For a square matrix Λ≥0, if ρ(Λ)<1, then (I−Λ)−1≥0, where ρ(⋅) is the spectral radius, and I and 0 are the identity and zero matrices, respectively.

3.

Main inequalities

Consider the following inequalities

where yi(t), γi(t), and ηij(t) are non-negative functions and αij≥0, i,j∈Nn.

Lemma 3.1. Regrading system (3.1), let the following hypotheses hold:

(H.1) For i,j∈Nn, there exist γ(t) and γi>0 such that

where γ∗(t)=γ(t), for t≥t0, and γ∗(t)=0, for t<t0.

(H.2) ρ(α)<1, where α=(αij)n×n.

Then, there is a κ>0 such that

Proof. For t≥t0, multiply eλ∫tt0γ(u)du on both sides of (3.1), and one has

where λ∈(0,mini∈Nn{γi}) is a sufficiently small constant which will be explained later. Define

i∈Nn and t≥t0. Obviously,

Further, it follows from (H.1) that

By (3.2)–(3.4), we have

By the definition of Hi(t), we get

i.e.,

where H(t)=(H1(t),...,Hn(t))T, ψ(t0)=(ψ1(t0),...,ψn(t0))T, Γ=diag(γ1,...,γn), and αeλη=(αijeληij)n×n. Since ρ(α)<1 and α≥0, then there is a small enough λ>0 such that

From Lemma 2.1, we get

Denote

From (3.5), we have

Therefore, for i∈Nn, we get

and then there exists a κ>0 such that

This completes the proof. □

Consider the following differential inequalities

where D+ is the Dini-derivative, yi(t), γi(t), and ηij(t) are non-negative functions, and αij≥0, i,j∈Nn.

Lemma 3.2. For system (3.6), under hypotheses (H.1) and (H.2), there are κ>0 and λ>0 such that

Proof. For t>t0, multiply e∫tt0γi(u)du (i∈Nn) on both sides of (3.6) and perform the integration from t0 to t. We have

The proof is deduced from Lemma 3.1. □

Remark 3.1. For a given matrix M=(mij)n×n, we have ρ(M)≤‖M‖, where ‖⋅‖ is an arbitrary norm, and then we can obtain some conditions for generalized exponential stability. In addition, for any nonsingular matrix S, define the responding norm by ‖M‖S=‖S−1MS‖. Let S=diag{ξ1,ξ2,...,ξn}, then for the row, column, and the Frobenius norm, the following conditions imply ‖M‖S<1:

(1) n∑j=1(ξiξj|mij|)<1 for i∈Nn;

(2) n∑i=1(ξiξj|mij|)<1 for i∈Nn;

(3) n∑i=1n∑j=1(ξiξj|mij|)2<1.

Remark 3.2. Ruan et al. [23] investigated the special case of inequalities (3.6), i.e., γi(t)=γi and ηij(t)=ηij. They obtained that system (3.6) is exponentially stable provided

From Remark 3.1, we know condition ρ(α)<1 (α=(αijγi)n×n) is weaker than (3.7). Moreover, we discuss the generalized exponential stability which contains the normal exponential stability. This means that our result improves and extends the result in [23].

4.

Main result

This section considers the pth moment generalized exponential stability of (1.1) by applying Lemma 3.1. To obtain the pth moment generalized exponential stability, we need the following conditions.

(C.1) For i,j∈Nn, there are c(t) and ci>0 such that

where c∗(t)=c(t), for t≥t0, and c(t)=0, for t<t0.

(C.2) The mappings fj and gj satisfy fj(0)=gj(0)=0 and the Lipchitz condition with Lipchitz constants Fj>0 and Gj>0 such that

(C.3) The mapping σij satisfies σij(t,0,0)≡0 and ∀u1,u2,v1,v2∈R, and there are μij(t)≥0 and νij(t)≥0 such that

(C.4) For i,j∈Nn,

(C.5)

where M=diag(m1,m2,...,mn), mi=(p−1)n∑j=1ρ(1)ijp+(p−1)(p−2)n∑j=1ρ(2)ij2p, Ω(k)=(ρ(k)ij)n×n, k∈N2, and p≥2.

Conditions (C.1)–(C.4) guarantee the existence and uniqueness of (1.1) [30].

Theorem 4.1. Under conditions (C.1)–(C.5), system (1.1) is pth moment generalized exponentially stable with decay rate −λ∫tt0c(s)ds, λ>0.

Proof. By the Itô formula, one can obtain

So we get

Since E[∫tt0pσij(s,zj(s),zj(s−δij(s)))zp−1i(s)dwj(s)]=0 for i∈Nn and t≥t0, we have

i.e.,

For i∈Nn and t≥t0, using the variation parameter approach, we get

For i∈Nn and t≥t0, conditions (C.2)–(C.4) and the Young inequality yield

Then, all of the hypotheses of Lemma 3.1 are satisfied. So there exists κ>0 and λ>0 such that

This completes the proof. □

Remark 4.1. Huang et al.[27] and Sun and Cao [21] considered the special case of (1.1), i.e., aij(t)≡aij, bij(t)≡bij, ci(t)≡ci, μij(t)≡μj, νij(t)≡νj, and δij(t)≡δj(t) is a bounded delay function. [27] showed that system (1.1) is pth moment exponentially stable provided that there are positive constants ξi,...,ξn such that N1>N2>0, where

and

The above conditions imply that for each i∈Nn,

Then

From Remark 3.1, we know condition (4.1) implies

and this means that this paper improves and enhances the results in [27]. Similarly, our results also improve and enhance the results in [10,11,26]. Besides, the results in [21] required the following conditions to guarantee the pth moment exponential stability, i.e.,

where

From the matrix spectral analysis [29], we can get

The above discussion shows that our results improve and extend the works in [21]. Similarly, our results also improve and broaden the results in [20].

Remark 4.2. When ci(t)≡ci, aij(t)≡aij, bij(t)≡bij, δij(t)≡δj, and σij(t,zj(t),zj(t−δij(t)))≡0, then (1.1) turns to be the following HNNs

or

where z(t)=(z1(t),...,zn(t))T, C=diag(c1,...,cn)>0, A=(aij)n×n, B=(bij)n×n, f(x(t))=(f1(z1(t)),...,fn(zn(t)))T, and g(zδ(t))=(g1(z1(t−δ1)),...,gn(zn(t−δn)))T. This model was discussed in [16,28]. For (4.3), using our approach can get the subsequent corollary.

Corollary 4.1. Under condition (C.2), if ρ(C−1D)<1, then (4.3) is exponentially stable, where D=(|aijFj|+|bijGj|)n×n.

Note that Lai and Zhang [28] (Theorem 4.1) and Chen et al. [16] (Corollary 5.2) required the following conditions

and

to ensure the exponential stability, respectively. From Remark 3.1, we know that Corollary 4.1 is weaker than Theorem 4.1 in [28] and Corollary 5.2 in [16]. This improves and extends the results in [16,28].

5.

Examples

Now, we give three examples to illustrate the effectiveness of the main result.

Example 5.1. Consider the following SDHNNs:

where c1(t)=10(t+1), c2(t)=20(t+2), a11(t)=b11(t)=0.5(t+1), a12(t)=b12(t)=t+1, a21(t)=b21(t)=2(t+2), a22(t)=b22(t)=2.5(t+2), f1(u)=f2(u)=arctanu, g1(u)=g2(u)=0.5(|u+1|−|u−1|), σ11(t,u,v)=√2(t+1)(u−v)2, σ12(t,u,v)=2√(t+1)(u−v), σ21(t,u,v)=√(t+1)(u−v), σ22(t,u,v)=√10(t+2)(u−v)2, δ11(t)=δ21(t)=δ12(t)=δ22(t)=0.5t, and ϕ(0)=(40,20).

Choose c(t)=1t+1, and then supt≥0{∫t0.5t1s+1ds}=ln2. We can find F1=F2=G1=G2=1, ρ(1)11=0.1, ρ(1)12=0.2, ρ(1)21=0.2, ρ(1)22=0.25, ρ(2)11=0.2, ρ(2)12=1.6, ρ(2)21=0.2, and ρ(2)22=0.5. Then

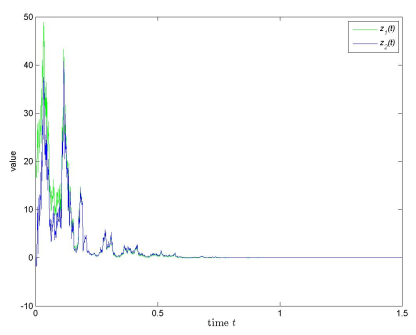

Then (C.1)–(C.5) are satisfied (p=2). So (5.1) is generalized exponentially stable in mean square with a decay rate −λ∫t011+sds=−λln(1+t), λ>0 (see Figure 1).

Remark 5.1. It is noteworthy that all variable coefficients and delay functions in Example 5.1 are unbounded, and then the results in [12,23] are not applicable in this example.

Example 5.2. Consider the following SDHNNs:

where c1(t)=20(1−sint), c2(t)=10(1−sint), a11(t)=b11(t)=2(1−sint), a12(t)=b12(t)=4(1−sint), a21(t)=b21(t)=0.5(1−sint), a22(t)=b22(t)=1.5(1−sint), f1(u)=f2(u)=arctanu, g1(u)=g2(u)=0.5(|u+1|−|u−1|), σ11(t,u,v)=√2(1−sint)(u−v), σ12(t,u,v)=√6(1−sint)(u−v), σ21(t,u,v)=√(1−sint)(u−v)2, σ22(t,u,v)=√(1−sint)(u−v)2, δ11(t)=δ21(t)=δ12(t)=δ22(t)=π|cost|, and ϕ(t)=(40,20) for t∈[−π,0].

Choose c(t)=1−sint, and then supt≥0∫tt−π|cost|(1−sins)∗ds=π+2. We can find F1=F2=G1=G2=1, ρ(1)11=0.2, ρ(1)12=0.4, ρ(1)21=0.1, ρ(1)22=0.3, ρ(2)11=0.4, ρ(2)12=1.2, ρ(2)21=0.1, and ρ(2)22=0.1. Then

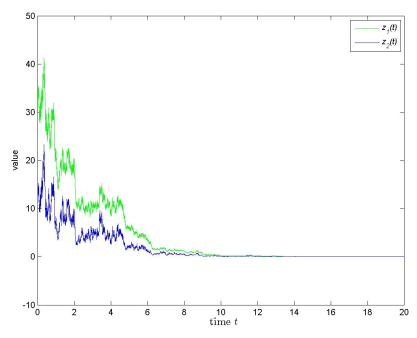

Then (C.1)–(C.5) are satisfied (p=2). So (5.2) is generalized exponentially stable in mean square with a decay rate −λ∫t0(1−sins)ds=−λ(t−cost+1), λ>0 (see Figure 2).

Remark 5.2. It should be pointed out that in Example 5.2 the variable coefficients ci(t)=0 for t=π2+2kπ, k∈N. This means that the results in [12,23] cannot solve this case.

To compare to some known results, we consider the following SDHNNs which are the special case of [12,16,20,21,22,23].

Example 5.3.

where c1=2, c2=4, a11=0.5, a12=1, b11=0.25, b12=0.5, a21=13, a22=23, b21=13, b22=23, f1(u)=f2(u)=arctanu, g1(u)=g2(u)=0.5(|u+1|−|u−1|), σ1(u)=0.5u, σ2(u)=0.5u, δ11(t)=δ21(t)=δ12(t)=δ22(t)=1, and ϕ(t)=(40,20) for t∈[−1,0].

Choose c(t)=1, and then supt≥0∫tt−1(1)∗ds=1. We can find F1=F2=G1=G2=1, ρ(1)11=38, ρ(1)12=34, ρ(1)21=16, ρ(1)22=13, ρ(2)11=18, ρ(2)12=ρ(2)21=0, and ρ(2)22=116. Then

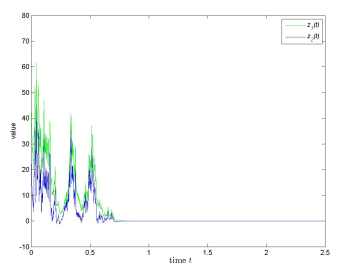

Then (C.1)–(C.5) are satisfied (p=2). So (5.3) is exponentially stable in mean square (see Figure 3).

Remark 5.3. It is noteworthy that in Example 5.3,

which makes the result in [20,21,22] invalid. In addition,

which makes the result in [16] not applicable in this example. Moreover

which makes the results in [12,23] inapplicable in this example.

6.

Conclusions

In this paper, we have addressed the issue of pth moment generalized exponential stability concerning SHNNs characterized by variable coefficients and infinite delay. Our approach involves the utilization of various inequalities and stochastic analysis techniques. Notably, we have extended and enhanced some existing results. Lastly, we have provided three numerical examples to showcase the practical utility and effectiveness of our results.

Author contributions

Dehao Ruan: Writing and original draft. Yao Lu: Review and editing. Both of the authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript for publication.

Use of AI tools declaration

The authors declare they have not used Artificial Intelligence (AI) tools in the creation of this article.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by the Talent Special Project of Guangdong Polytechnic Normal University (2021SDKYA053 and 2021SDKYA068), and Guangzhou Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (2023A04J0031 and 2023A04J0032).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

DownLoad:

DownLoad: