1.

Introduction

Soil contributes largely to the global carbon cycle because it comprises of an active carbon pool [1]. In the terrestrial ecosystem, soil is considered to be the largest sink of organic carbon storing more than three times carbon compared to the amount stored in the atmosphere and 3.8 times more than the amount stored in biotic pool [2]. Therefore, the substantial sequestration of carbon in soils can provide a significant opportunity to mitigate global warming [3]. Enhancing the capture and storage of atmospheric CO2 in different land use systems can be a successful approach to lower its concentration while also improving the quality of soil [4,5]. Soil profile in the top 1m stored 1500 Pg C soil organic carbon (SOC) globally, out of which Indian soil holds about 9 Pg C where the Himalayan zones account for about 33% of the total SOC reserves owing to thick forest vegetation [6]. SOC can either be increased or decreased depending on various factors such as soil type, climate, topography and soil management practices. However, SOC is greatly influenced by vegetation through organic matter input and therefore land use change is one of the most important factors which influences SOC stock build up. For example, it was reported that the conversion of farmland to apple orchard led to the decrease in the quality of soil owing to the reduced SOC stocks [7]. Soil carbon stock, following forest-pasture conversions, decreased to 51% in 20–30 years old pasture converted from wet tropical forest in Costa Rica, while SOC stock increased to 164% in a 33 years old leguminous pasture converted from native vegetation in Western Australia [8]. A meta-analysis reported that SOC stock decreased 13% and 42% when native forest converted to plantation and crop land respectively [9].

In natural ecosystem like forest and agroforestry, the soils are less disturbed due to less cultural operations and therefore may contain adequate nutrients and soil microorganisms when compared to agricultural lands [10,11,12]. Intensive management and cultural practices in agricultural lands increase the turnover rates of macro agammaegates and lead to destabilization of the labile soil organic matter compounds [13]. Study reported from Northeast India showed the highest SOC stock in dense forest (140.4 Tg) and the least in shifting cultivation (10.7 Tg) with a total SOC stock (339.82 Tg), irrespective of the land use system for an area of 10.10 million ha, wherein forest soils contributed more than 50% with great implications for SOC sequestration in the region [14]. Studies from northern Bangladesh reported highest SOC concentration in agroforestry system (1.063%) and least in fallow land (0.249%) [15], whereas a similar study from homegardens in Aizawl, Mizoram reported SOC stock of 258.43 t C ha−1 in 1 m soil depth [16]. Soil carbon sequestration proves to be a key indicator of soil health and crop efficiency [17,18], responsible for climate change mitigation and at the same time improving soil physical properties through moisture and nutrient retention [19]. However, the removal of biomass through deforestation and land use change can accelerate soil erosion resulting in significant loss of soil organic carbon from the surface soil [20,21]. The state of Mizoram reported a high percentage of forest cover (86.27% with respect to the total geographical area); however, forest cover has decreased considerably (by 531 km2 from 2015 to 2017) due to shifting cultivation, biotic pressure, illegal felling, conversion of forest lands for developmental activities and agriculture expansion [22]. Despite the great potential of forest to sequester soil organic carbon, studies on SOC stock in forest and various land use conversions are limited in Mizoram [23,24,25]. Estimating SOC stock in various land uses has become very essential because it will aid policy makers to work out techniques for managing land use systems sustainably as well as preventing extreme loss of SOC. Hence, the present study was undertaken with objectives to estimate SOC stock in different land uses and also to assess the relationship between SOC and land use types in Mizoram.

2.

Materials and methods

2.1. Study site

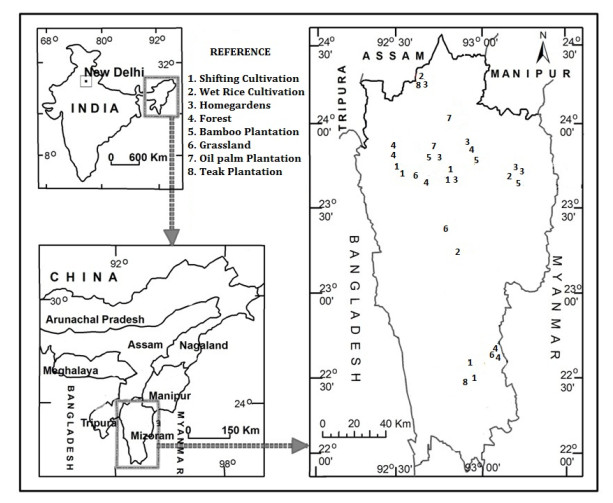

This study was conducted in the whole of Mizoram which is located between 21°58' N to 24°35' N, and 91°15' E to 93°29' E encompassing a total area of 21,081 km2 (Figure 1). The state is bounded internationally by Myanmar and Bangladesh on the southern part and domestically by Manipur, Assam and Tripura on the northern part. The climatic condition is mild with relatively cool summer 20 to 29 ºC but becomes warmer with temperature exceeding 30 ºC. In winter, the temperature varies between 7 to 22 ºC. The winter season is short and summer long with heavy rainfall from the south-west monsoon with an average annual rainfall of 2450 mm. The monsoon period starts from May lasting till September with slight rain in the cold season. A summary of the site characteristics including climate, vegetation and soil of the eight land uses studied are shown in Tables 1 and 2. The age of the different land uses were determined with the help of the landholders and villagers.

2.2. Soil Sampling and analysis

In each land use, five sample plots of 20 × 20 m2 were randomly selected, their locations and altitude recorded by a GPS. Within each sample plot, soils were collected from four corners and in the centre of the square plot at three depth classes: 0–15, 15–30 and 30–45 cm respectively. The five sub samples in each plot were mixed thoroughly and a composite sample was obtained for each depth class. A total of 120 samples (8 land use × 5 plots × 3 depths) were collected for SOC estimation. Similarly, a total of 120 samples (8 land use × 5 plots × 3 depths) for soil bulk density (BD) measurements were collected with the help of a soil corer of known volume. In the laboratory, the composite soil samples were mixed thoroughly, air-dried, crushed and passed through 2 mm sieve and replicates were made to analyse soil organic carbon content through Walkley and Black method [26]. For each depth, three replicates from each composite sample were analysed. Soil bulk density was determined by dry weight method by oven drying the soils at 80 ºC for 24 hours and rocky fragments (>2 mm) were separated. Soil pH was measured using a pH meter and soil textural class was identified following ISSS soil mixture classification system.

2.3. Soil organic carbon stock estimation

Soil carbon stock for each site was estimated by multiplying with corresponding values of fine bulk density and SOC content. SOC stock was calculated following the formula given by Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) [27].

where, C storage—representative C stock for the soil of interest Mg C ha−1. SOC—concentration of soil organic carbon in a given soil mass, g C kg−1. Bulk Density—soil mass per sample volume, g cm−3. Depth—horizon depth or thickness of soil layer, m. Frag—% volume of coarse fragments (stone and gravel)/100, dimensionless.

2.4. SOC stock change estimation

SOC stock change (Mg C ha−1) is estimated depending on the SOC stock changes between previous (CLU0) and present (CLUn) land use type [28]. The carbon stock of the previous land use type was set as the baseline for calculating the rate of change in SOC stock (Mg C ha−1 yr−1) after land use conversion. The following equation is used to calculate the rate of change (Rstock):

2.5. Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics analysis was carried out using SPSS version 17.0. An analysis of variance (ANOVA) was done to evaluate if different land uses have significant SOC stock distribution and significant effect (P < 0.05) was determined with Tukey honest significant difference (HSD) post hoc multiple comparisons.

3.

Results and discussion

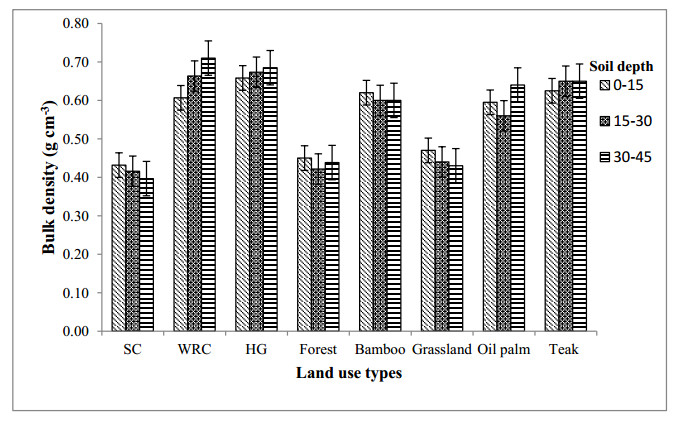

Bulk density (BD) of fine soil (<2 mm) in different land use types across varying depths ranged between 0.40 to 0.71 g cm−3 (Figure 2). On an average, bulk density of fine soil in 0–45 cm soil profile was lowest in shifting cultivation (0.42 g cm−3) and the highest in forest (0.68 g cm−3). The higher soil bulk density in homegardens and wet rice cultivation as compared to other land uses maybe due to the cultivation practices such as tillage which cause soil compaction. Many studies have indicated that with the increase in soil depth, bulk density also tends to increase [29,30]. Conversely, our studies revealed that except in wet rice cultivation, the other land uses did not indicate any particular trend of bulk density increasing with increase in depth. It was reported that bulk density higher than 1.6 g/cm3 is unfavourable for plant growth as it can restrict the penetration of plant roots in clay loam soil [31]. In regard to this, the soil bulk density in all the land uses studied was found to be clearly below the critical value denoting that there is no extreme soil compaction.

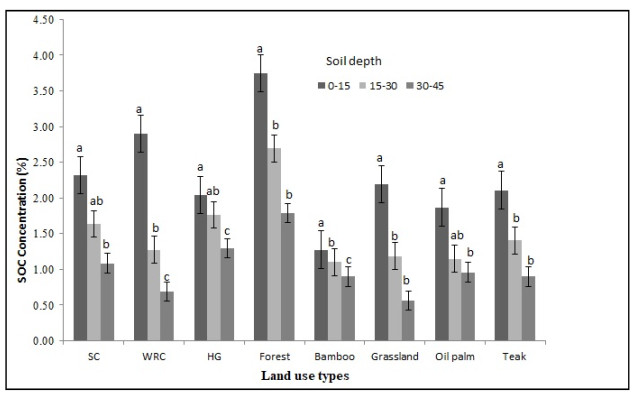

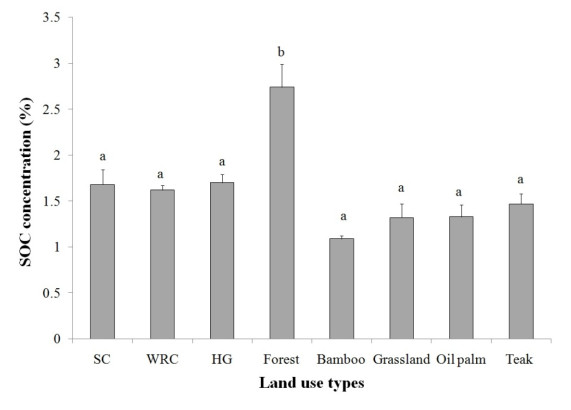

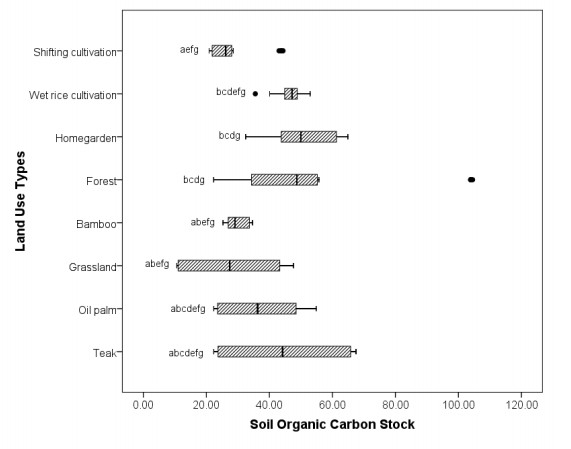

Amongst all the land uses studied, forest (natural) recorded the highest SOC concentration in all soil depths with 3.74, 2.70 and 1.79% in 0–15cm, 15–30 cm and 30–45 cm respectively. Bamboo forest recorded the least SOC concentration at 0–15 and 15–30 cm depth (1.28%, 1.10%) while grassland recorded the least (0.56%) at 30–45 cm depth (Table 3). SOC concentration decreased with increasing soil depth class in each of the land use types (Figure 3). On an average, forest soils have the highest SOC concentration compared to other land uses studied (Figure 4). The highest SOC concentration in the forest can be related to the presence of more vegetation generating more litter falls which are returned to the soils as organic matters. In the top surface soil (0–15 cm), maximum SOC stock was found in wet rice cultivation (26.36 Mg C ha−1) followed by forest (24.50 Mg C ha−1) and minimum in bamboo plantation (11.81 Mg C ha−1) (Table 4). Many studies have shown that paddy soils have the potential to hold a great amount of recalcitrant/stable carbon [32,33]. In continuous wet rice cultivation, the built up of organic matter is very high due to their submerged conditions because in such a state, the decomposition of organic matter and SOC mineralization is very slow due to the anaerobic condition leading to higher net carbon storage [34]. Therefore, this may be one of the reasons why SOC stock in the upper 0–15 cm is higher in wet rice cultivation than the other land uses. In soil depth of 15–30 cm and 30–45 cm, the maximum SOC stock was recorded in homegarden and the least in grassland (Table 4). Grasslands have the ability to store a considerable amount of soil carbon in the upper stratum of the soil, however, the lower strata accumulates very less carbon which may be due to the shallow rooting of the grasses and absence of deep rooting trees. Highest SOC concentration and SOC stock in the top soil and decreasing with increase in soil depth from the study is in harmony with similar studies carried out by other researchers [11,23,35]. Overall amongst the different land uses, the mean SOC stock in 0–45 cm soil profile was highest in forest (52.74 Mg C ha−1) followed by homegarden (50.85 Mg C ha−1), wet rice cultivation (46.21 Mg C ha−1), teak (44.66 Mg C ha−1), oil palm (36.73 Mg C ha−1), bamboo (29.83 Mg C ha−1), shifting cultivation (27.87 Mg C ha−1) and lowest in grassland (27.68 Mg C ha−1) as presented in Figure 5. This is in disagreement with other studies where considerably high amount of SOC stock in grassland (75.76 Mg C ha−1) than plantations (46.13 Mg C ha−1) [36]; and higher value of SOC stock in grassland (95.54 Mg C ha−1) than in agricultural land (75.70 Mg C ha−1) [11] were reported. The significantly lower SOC stock in grassland reported in our study as compared to the other land uses might be because of the absence of deep rooted trees and fewer canopy covers. The potential for soils to store atmospheric carbon is primarily affected by the balance between the rate at which fresh photosynthetic material i.e. roots and exudates, is deposited and the time required by these carbon inputs to get broken down through heterotrophic respiration [37]. Moreover, as root tissue is more recalcitrant to degradation and mineralization than top soil litter, root derived carbon has long residence time [38]. Greater accumulation of organic matter in soils under tree canopies than open grassland can reduce leaching. Also, due to the absence of canopy covers, the soils in grasslands are directly exposed to the solar radiation thereby increasing the rate of mineralization. Similar findings have been reported by several other researchers [39,40]. Shifting cultivation recorded significantly lower (P < 0.05) SOC stock as compared to wet rice cultivation, homegardens and forest. Soils in shifting cultivation are usually much depleted due to reduction in biomass, reduced nutrients because of the shortened fallow periods and thus resulting in reduced soil organic carbon [41]. Another reason might be due to the steep slope condition of the state combined with heavy rainfall which leads to incidence of more soil erosion consequently leading to loss of SOC of the surface soils. A comparatively lesser SOC stock value of 29.83 Mg C ha−1 in bamboo forest was observed from the study where other similar studies from Mizoram reported 46.04 Mg C ha−1 [25]. This may be due to several reasons such as location, age of the bamboo stands and density of the bamboo stands. It was also reported by other studies that bamboo leaves releases allelopathic compounds during decomposition [42,43] which may reduce the growth of seedlings leading to low species richness which in turn reduces the input of litter thereby affecting the soil carbon stock. A correlation analysis of SOC concentration showed positive significant relationship with SOC stock, soil moisture content, clay and sand at P < 0.001 level of significance. However, it correlated negatively with bulk density at P < 0.001 and silt at P < 0.05 level of significance respectively (Table 5). The positive relationship between SOC concentration and soil moisture content implies that SOC increases with increase in soil moisture content. This might be due to the microbial activity as soil moisture plays an important role in regulating the activity of soil microbes and determining the microbial population in forest floor [44]. Similar observations were reported by other studies too [45,46]. Furthermore, the significant positive relationship between SOC with clay and sand indicates the importance of fine soil particles for SOC storage for longer duration, especially clay minerals which protects against weathering and microbial degradation. Additionally, the relationship of SOC between different land use types is presented in Table 6. The significant positive relationship of SOC between different land use types may be due to similar land management practices such as in shifting cultivation and homegarden where the lands are regularly subjected to practices such as weeding and hoeing. Whereas, in case of shifting cultivation, grasslands and bamboo plantation, the lower input of litter due to less tree canopies might be one of the probable reasons. Forest exhibited a positive significant relationship only with teak plantation which may be attributed to the denser understory vegetation and less soil disturbances in both the land uses. Similarly, the significant negative relationship between oil palm with homegarden and bamboo; teak with grassland and oil palm can also be due to different management practices and types of inputs.

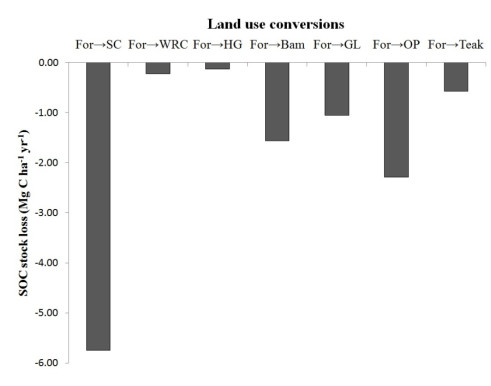

Meanwhile the estimated loss of SOC stock following conversion of forest to different land uses is presented in Figure 5. Result indicated a maximum loss of SOC stock when forest was converted to shifting cultivation (−5.74 Mg C ha−1 yr−1) followed by oil palm plantation (−2.29 Mg C ha−1 yr−1), bamboo plantation (−1.56 Mg C ha−1 yr−1) and the least in homegardens (−0.14 Mg C ha−1 yr−1). This indicates that emphasis should be given on proper management of shifting cultivation with respect to its intensity of practice and adoptability. The loss in SOC stock when forest is converted to other land use systems was also reported by other studies [8,9]. However, our research did not take into consideration of many other factors which are responsible for the gain or loss of SOC stock such as climate, altitude, soil types, physical, chemical, microbiological, biochemical properties of soil, etc. For instance, the plants community and productivity can be altered by the variations in climate along an altitudinal gradient which ultimately leads to the increase or decrease in the amount and the rate of soil organic matter (SOM) mineralization [47,48,49]. The decrease in temperature with increasing altitude has been proven to reduce the turnover rate of SOC in forest soils and thereby enhancing SOC stabilization and storage [50]. Furthermore, soil microbes play a huge role in the storage and stabilization of soil organic carbon as soil microbes can accelerate the rate of SOM mineralization. Studies reported that the higher microbial biomass in grassland comparing to arable land increased the mineralization of SOM [51]. Also, the increase or decrease in SOC stock may have been affected by indirect factors such as mycorrhizal colonization and soil agammaegate size [52,53] Therefore, it is of utmost importance to consider these parameters while estimating SOC stock change in any land use system.

4.

Conclusions

This study has shown that land use system is one of the major factors affecting soil organic carbon stock. It supports the existing knowledge of forest soils holding the maximum carbon stock. Our findings also indicated that a substantial amount of organic carbon can be stored in wet rice cultivation but shifting cultivation, which is a more dominant form of agriculture in Mizoram, resulted in a greater loss of SOC stocks due to their nature of practice and topography. Based on the results, SOC stocks in other land uses were low compared to forest and this indicate the presence of a good potential to sequester carbon in the soils of these land uses in the study area. Therefore, a detailed study of different land uses in Mizoram, and identification of its appropriate management practices aimed to increasing inputs and reduce soil organic carbon losses need to be conducted in the study area. Soil carbon sequestration will eventually minimize effects of climate change.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Funding Agency: Department of Science and Technology, New Delhi under AICP- North-East CO2 Sequestration Research Program of Ministry of Science and Technology, Government of India (DST/1S-STAC/CO2-SR-227/14(G)-AICP-AFOLU-IV). The authors would also like to thank the editors and anonymous reviewers for their critical and valuable suggestions on this paper.

Conflict of interest

All authors declare no conflicts of interest in this paper

DownLoad:

DownLoad: