1.

Introduction

Oil and gas fields are very severe environments for metals, and high corrosion resistance and strength steels are generally used. Stress corrosion cracking (SCC), sulfide stress cracking (SSC) and hydrogen embrittlement (HE) are principal corrosion problems of steels used in oil and gas environments. The corrosion behavior of steels has been examined in simulated oil and gas environments [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16]. Kimura et al. reported that the modified 13 mass% Cr stainless steel showed excellent resistance to CO2 corrosion and resistance to SSC [2]. Sunaba et al. investigated the effects of chloride ion concentration on the passive and corrosion product films of modified martensitic stainless steels at high temperatures in CO2 environments [7]. They reported that molybdenum improved stability of the corrosion product films in high temperature CO2 and the presence of chloride ions. Hashizume et al. introduced a solution flow type micro-droplet cell and a glow discharge optical emission spectrometer (GDS) to investigate the electrochemical behavior of low carbon 13 mass% Cr welded joints and the effect of a post welded heat treatment (PWHT) in oil and gas environments [17]. They reported that the PWHT eliminated the Cr depleted layer formed during welding, and reduced the SCC susceptibility.

Hashizume et al. also investigated the effects of chemical composition and tempering of martensitic stainless steel on corrosion rates and pitting potentials in simulated CO2 gas wells [13]. They reported that the corrosion rate and the pitting potential in environments simulating CO2 gas wells were governed mainly by the amount of Cr in the steel matrix. The effect of acetate ions on the structure of surface oxide films and corrosion behavior of 13 mass% Cr stainless steel in 25% NaCl solutions were investigated by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) and electrochemical techniques [18]. It was found that the intensity ratios of both Fe0/(Fe3+ + Fe2+ + Fe0) and Cr0/(Cr3+ + Cr0) decrease with increasing concentration of CH3COONa, and after a minimum increased with further increasing in CH3COONa concentration. Fierro et al. applied XPS for the analysis of the corrosion film formed on 13 mass% Cr martensitic stainless steel in CO2-H2S-Cl− [19,20]. The presence of H2S resulted in more the formation of the less protective Fe sulfide-rich and Fe oxide-rich layers, while the presence of CO2 resulted in Cr oxide enrichment in the outermost layers of the film. Islam et al. investigated the corrosion layer on pipeline steel in CO2 containing environments (sweet environments) [21].

However, the effects of environmental parameters such as pH, the concentration of CH3COONa, and CO2 on corrosion behavior of stainless steels have not been fully elucidated. The purpose of this study is to investigate the effects of the concentrations of CH3COONa and CO2 on the corrosion behavior of 13 mass% Cr martensitic stainless steels in simulated oil and gas environments.

2.

Materials and method

2.1. Samples and preparation

Plates of 13 mass% Cr martensitic stainless steel (12.4 mass% Cr, 0.2 mass% C) with 3 mm thickness were used as samples. The sample size for electrochemical and XPS analysis was 7 × 15 mm, and for Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR) analysis was 15 × 15 mm.

For electrochemical measurement, Cu wires were soldered to the samples and then embedded in epoxy resin. The exposed surface of the embedded samples was ground with SiC abrasive paper from #240 to #1200 grit size. For immersion corrosion tests, samples were embedded in epoxy resin. The exposed surfaces of the samples were ground with SiC abrasive paper from #240 to #2400 grit size. The samples were ultrasonically cleaned in ethanol and in highly purified water, before the tests.

2.2. Solutions

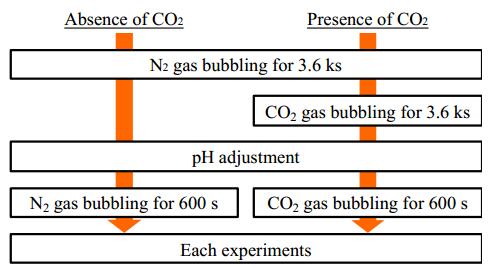

Solutions of 5% NaCl with 0, 0.4, 4.0 g/L CH3COONa were used as test solutions. The pH of the solutions was adjusted to 3.5 by HCl. Before the experiments, N2 gas was bubbled through the solutions for 3.6 ks to reduce the concentration of dissolved O2 as low as possible, and then CO2 gas was bubbled as needed. The solution temperature was 353 K, and detailed procedures of the gas bubbling and pH adjustment are illustrated in Figure 1. During experiments, N2 or CO2 gas flowed over the solutions.

2.3. Anodic potentiodynamic polarization measurement

Anodic potentiodynamic polarization measurements were carried out in a three electrode cell. A Pt plate and Ag/AgCl sat. KCl was used as counter and reference electrodes respectively. The samples were immersed in the solutions for 21.6 ks and measured the immersion potential, Eim, and then the polarization measurements with a scan rate of 0.5 mV/s were started from (Eim - 10) mV until current density reached 1 mA/cm2. After the measurements, samples were rinsed with highly purified water and dried in a desiccator, and then the surface observations were performed with an optical microscope. Samples with crevice corrosion were discarded.

2.4. Immersion corrosion tests and surface analysis

The samples were immersed in the solutions for 21.6 ks. After the immersion, samples were rinsed with highly purified water and dried in the desiccator. The sample surfaces were analyzed by XPS (JEOL Ltd., JPS-9200). For the XPS analysis, Mg Kα (1253.6 eV) was used as the X-ray source, and the analysis area was 1 × 1 mm. The XPS depth analysis was carried out by sputtering with Ar ions. The sputtering time was converted to depth by the sputtering rate of SiO2. The wide range of depth profiles of Fe, Cr, and O were obtained by GDS (Horiba-Jobin Yvon, JY 5000 RF). The analysis area was 4 mm in diameter. The FT-IR (JASCO, FT-IR 4700) was used to determine the organic substances on the samples. The IR spectra were measured by reflection absorption spectroscopy (RAS) with the resolution of 1 cm−1. The background spectra were obtained with gold evaporation mirror and the subtracted the obtained samples spectra. The surface observation was carried out with a scanning electron microscope, SEM (JEOL Ltd., JSL6510-LA).

3.

Results and discussion

3.1. Anodic polarization curves

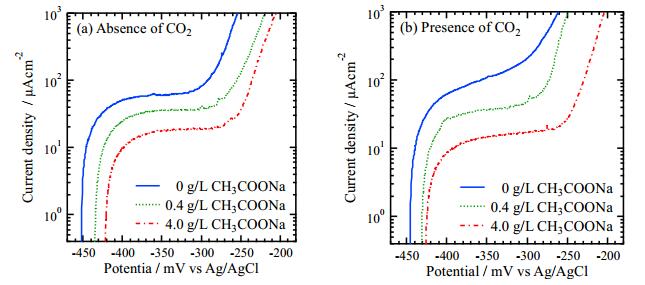

Anodic polarization curves were measured after 21.6 ks immersion and are shown in Figure 2. All curves except for 0 g/L CH3COONa in the presence of CO2 have the plateau region in the current, which implies that the corrosion reaction reaches a temporary steady state. The currents of plateau regions are higher than that of general passive current [22]. This result suggests that the passive state may not be achieved in the experimental conditions of this study. The current suddenly increased as the potential moves to a positive direction, which may imply the initiation of pitting corrosion. Hereafter, the plateau region in the current is called the average current density of the flat region, iflat, and the potential at 1 mA/cm2 is called pitting potential, Epit.

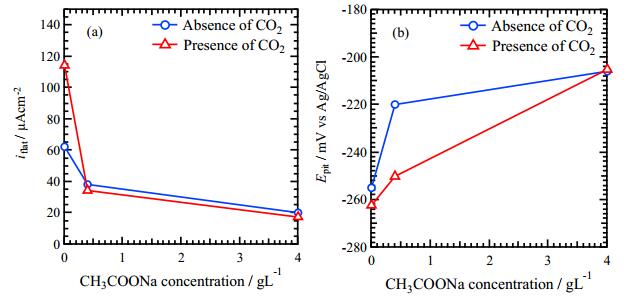

The relationships between these two parameters, iflat and Epit, and the CH3COONa concentration are shown in Figure 3. In Figure 3a, the iflat decreases with increasing CH3COONa concentration independent of CO2 bubbling, implying that adding CH3COONa inhibits the corrosion reaction. In Figure 3b, Epit obtained in the solutions of the presence of CO2 increases with increasing CH3COONa concentration, however, the effect of CH3COONa addition is not significant in the solutions of an absence of CO2.

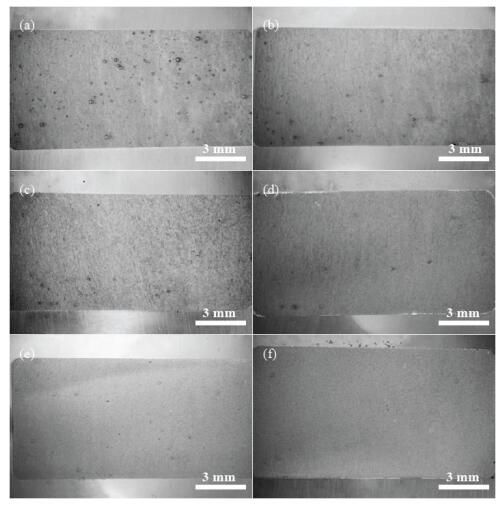

The surface optical images of the samples after the polarization tests are shown in Figure 4. Dark spots which may be related to pitting corrosion are observed, and the number of the spot decreased with increasing concentration of CH3COONa. This result coincides with Figure 3b.

3.2. XPS spectra

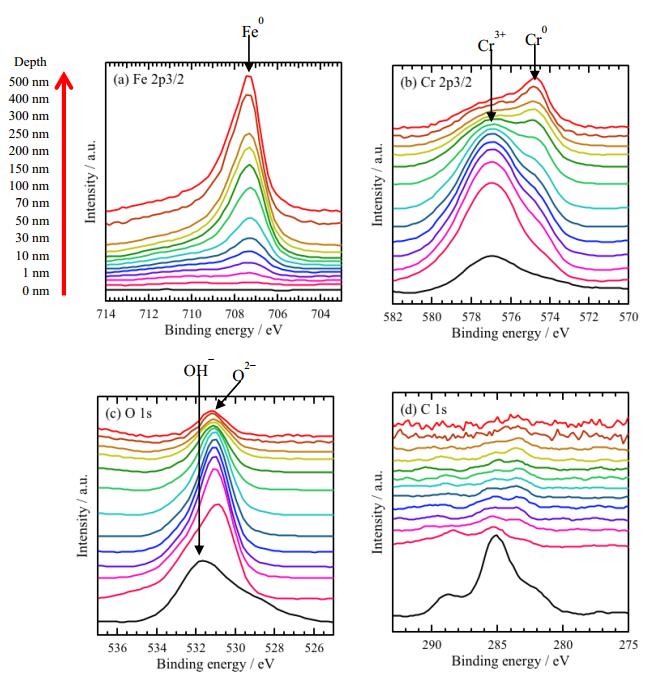

The sample surfaces were examined by XPS after immersion in 4.0 g/L CH3COONa absence of CO2 for 21.6 ks. Figure 5 shows XPS narrow scan spectra of (a) Fe 2p3/2, (b) Cr 2p3/2, (c) O 1s, and (d) C 1s at different depths. In the narrow scan spectra of Fe 2p3/2 (Figure 5a), no peak is observed from 0 and 10 nm, while peaks around 707 eV are measured depth deeper than 10 nm. The peaks are attributed to Fe0+ [23,24,25,26,27], and the intensity of the peak increases with depth. In the narrow scan spectra of Cr 2p3/2 (Figure 5b), the peaks around 577 eV are observed depth from 0 nm to 70 nm. The peaks are attributed to Cr3+ [23,25,26,27], and the intensity decreases with depth. The peaks around 574 eV are appeared after sputtering. The peaks are attributed to Cr0+ [23,25,26,27], and the intensity of the peak increases with depth.

In Figure 5c, the peaks around 532 eV attributed to OH− [23,25,26,27] is observed on the surface (at 0 nm depth). As sputtering, the peaks around 530 eV appear. The peaks are attributed to O2− [23,25,26,27], and the intensity changed with depth. Form Fe, Cr and O narrow scan spectra, corrosion product layer formed on the steel surface has a double layer structure as an outer layer; Cr hydroxide, and an inner layer; Cr oxide. In Figure 5d, peaks are observed on the surface (at 0 nm depth), and no peak is observed after sputtering. The peaks could not be attributed, however, the result suggests that the CH3COO− in the solution may exist only on the surface.

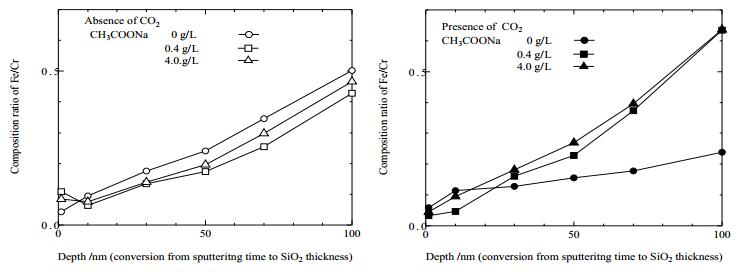

To investigate the composition of sample surface after immersion, a composition ration of Fe and Cr was calculated from XPS narrow scan spectra. Figure 6 shows composition ratio of Fe/Cr as a function of depth. The ratio increases with increasing depth, however, no significant difference with solution composition is observed. These results indicate that the composition ratio of Fe/Cr ratio at the surface is independent of the chemical composition of the used solution and CO2 bubbling.

3.3. GDS and FT-IR analysis

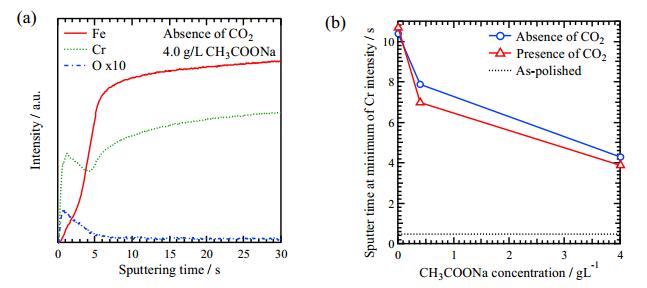

It is needed to investigate the depth profile of elements in the sample after the immersion tests. GDS was applied to measure the depth profiles of Fe, Cr and O. The depth profile of the sample immersed in 4.0 g/L CH3COONa solution absence of CO2 is shown in Figure 7a. The Fe intensity is low at the initial and it increases sharply as sputter time longer than 5 s. The Cr intensity shows a peak about 2 s and a minimum about 5 s. The O intensity shows peak around 1 s and becomes low after 5 s sputtering. These results suggest that the Cr rich layer exists until Cr intensity reached minimum. The sputter time at a minimum of Cr intensity decided from GDS spectra. Figure 7b shows the sputtering time at a minimum of Cr intensity as a function of CH3COONa concentration. The sputter time at minimum of Cr intensity decreases with increasing CH3COONa concentration. This result indicates that Cr rich layer becomes thinner with increasing CH3COONa concentration.

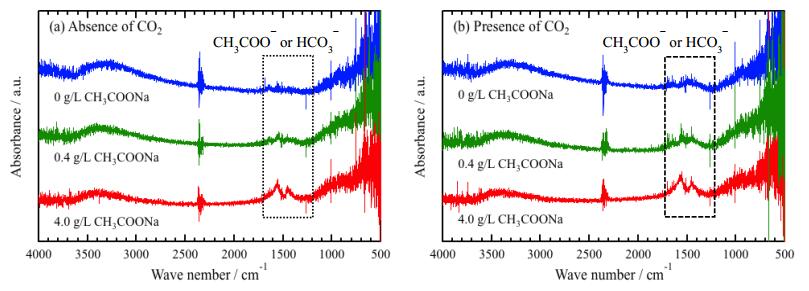

It was suggested that organic substances in the solution adsorbed on the surface from XPS analysis. FT-IR applied to analyze the organic substances on the surface, and obtained spectra are shown in Figure 8. The background spectrum was subtracted to reduce peaks related to CO2 and H2O in the environments. However, the residue of CO2 related peaks are still observed around 2400~2300 cm−1 [28,29]. The peaks around 1700~1300 cm−1 are attributed to CH3COO− or HCO3− [30,31], and the intensity of the peaks increases with increasing CH3COONa concentration. The intensity obtained in presence of CO2 shows lager value independent of CH3COONa concentration. These results indicate that CH3COO− or CO32− adsorbs on the surfaces.

3.4. Surface images after immersion corrosion test

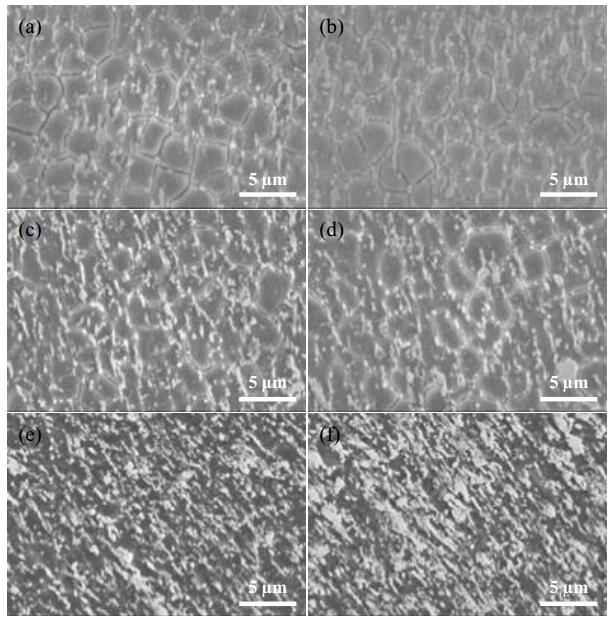

Surface morphologies of the samples after 21.6 ks immersion are shown in Figure 9. In Figure 9a, b, uneven surface with dark lines are observed in 0 g/L CH3COONa. In Figure 9c, d, a small number of dark lines are observed in 0.4 g/L CH3COONa. However, their size and length are almost the same as observed in 0 g/L CH3COONa. Smooth surfaces without dark lines are observed in 4.0 g/L CH3COONa (Figure 9e, f). There are precipitates on the surfaces in all samples, and size and number are changed with CH3COONa concentration. Little difference of the surface morphology is observed in the presence and absence of CO2 in the solutions.

4.

Discussion

4.1. Effect of CO2 gas bubbling

It is known that dissolved CO2 produced carbonic acid and H+.

In this experiment, it is considered that the cathodic reaction is the hydrogen evolution reaction because the pH of the used solutions was 3.5. The reaction may change the pH of the solution during polarization measurement. If CO2 gas flowing during the experiments, Eqs 1 and 2 may occur continuously and the carbonic acid acts as the source of H+. Therefore, the pH may be maintained during the polarization tests. This is a possible reason for iflat of 0 g/L CH3COONa in presence of CO2 showed the largest value as shown in Figure 3a. The supply of H+ by Eq 2 in presence of CO2, make it possible to increase corrosiveness of the solution and may reduce Epit as shown in Figure 3b.

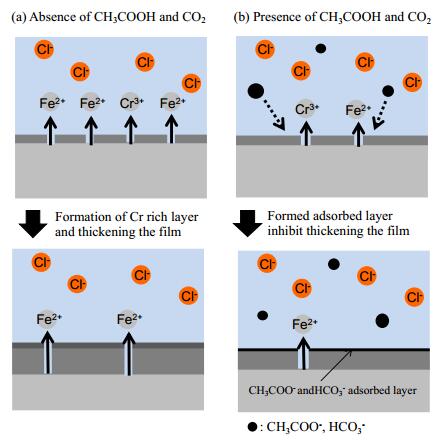

4.2. Effect of CH3COONa and CO2 on corrosion process

In this experiment, iflat decreased with increasing concentration of CH3COONa, while a small difference in surface composition was observed by surface analysis. The thickness of the Cr rich layer changed with the concentration of CH3COONa that was observed by GDS, and the adsorptions of CH3COO− or HCO3− on the surface were observed by FT-IR. These results may closely relate to corrosion process. Schematic representation of the corrosion process in these experimental conditions is shown in Figure 10. A highly protective layer is formed on the steel surface when the absence of CH3COONa and CO2 in the solution (Figure 10a). The corrosion is progressed by Cl−. The Cr rich layer is formed on the surface because of preferential Fe dissolution [32,33]. The thickness of the Cr rich layer may become thicker and then reaches a certain value as metal dissolution. In the case of CH3COONa and CO2 are present in the solutions, CH3COO− and HCO3− adsorb on the steel surface (Figure 10b). The absorbed layer may inhibit the dissolution of metals, therefore, the amount of dissolved metals decreases and relatively thin Cr rich layer is formed.

5.

Conclusion

The influences of CH3COONa and CO2 on the corrosion behavior of 13 mass% Cr martensitic steels in simulated oil and gas environments were investigated with electrochemical and surface analysis techniques. Following conclusions may be drawn:

(1) There was the plateau region of the current density, iflat, in the anodic polarization curves, and the iflat decreased with increasing CH3COONa concentration. In the case of the solutions with CH3COONa, little effect of CO2 on the iflat was observed. A pitting potential, Epit shifted to the positive direction as increasing CH3COONa concentration, and showed the negative value by adding CO2.

(2) The Cr enriched layer formed on the surface of the sample after the immersion test, and the thickness of the layer became thinner as increasing CH3COONa concentration. The adsorbed CH3COO− and HCO3− on the sample surfaces prevented the corrosion.

Acknowledgements

An observation of SEM was conducted at the Laboratory of XPS analysis, Joint-use facilities, Hokkaido University, supported by Material Analysis and Structure Analysis Open Unit (MASAOU). XPS analysis was conducted at the Laboratory of XPS analysis, Joint-use facilities, Hokkaido University, supported by 'Nanotechnology Platform' Program of the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT), Japan.

Conflict of interest

All authors have no conflict of interest directly relevant to the contents of this article.

DownLoad:

DownLoad: