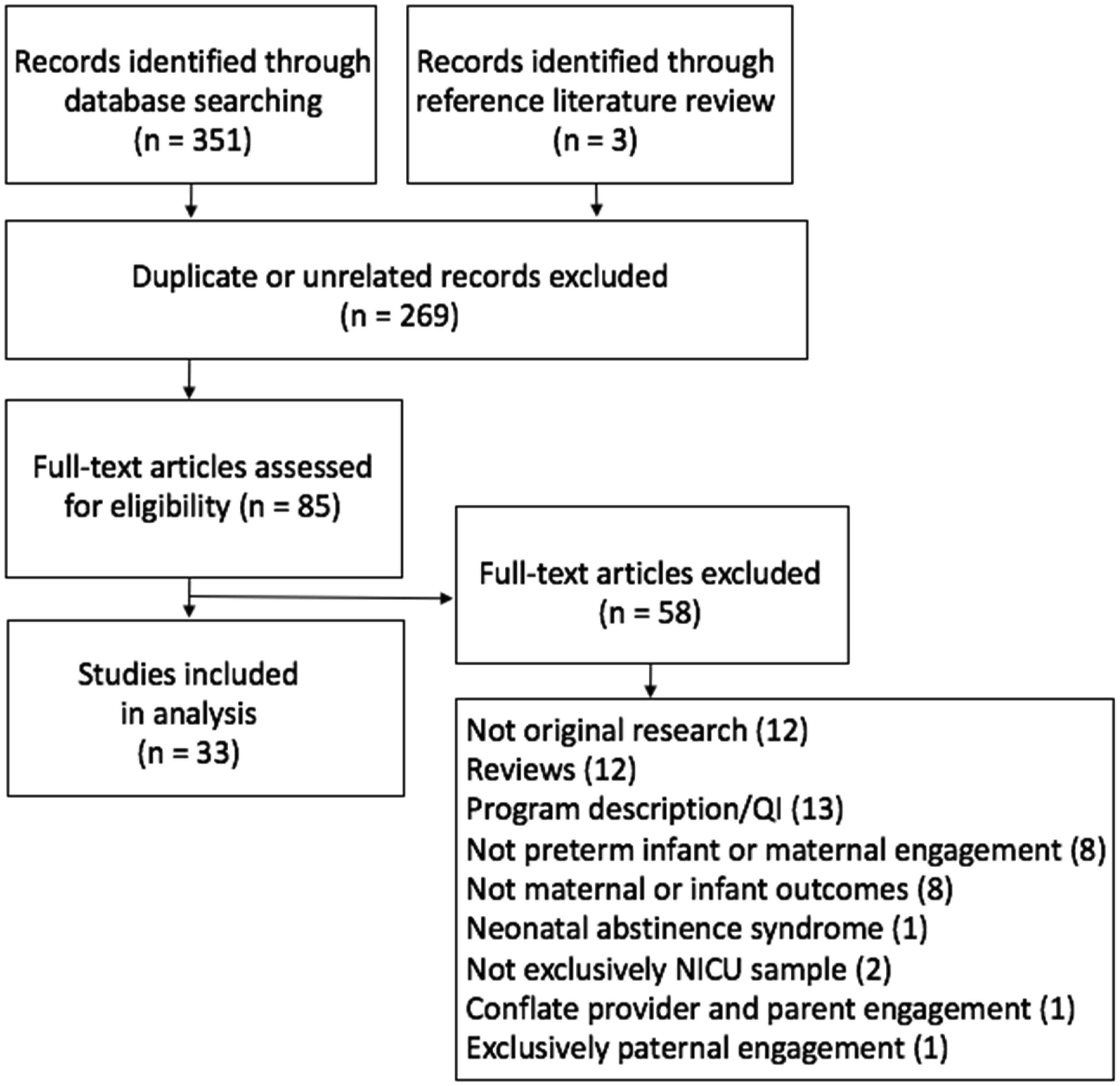

Hospitals and perinatal organizations recognize the importance of family engagement in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU). The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) defines family engagement as “A set of behaviors by patients, family members, and health professionals and a set of organizational policies and procedures that foster both the inclusion of patients and family members as active members of the health care team and collaborative partnerships with providers and provider organizations.” In-unit barriers and facilitators to enhance family engagement are well studied; however, less is known specifically about maternal engagement’s influence in the NICU on the health of infants and mothers, particularly within U.S. social and healthcare contexts. In this integrative review, we examine the relationship between maternal engagement in the NICU and preterm infant and maternal health outcomes within the U.S. Results from the 33 articles that met inclusion criteria indicate that maternal engagement in the NICU is associated with infant outcomes, maternal health-behavior outcomes, maternal mental health outcomes, maternal-child bonding outcomes, and breastfeeding outcomes. Skin-to-skin holding is the most studied maternal engagement activity in the U.S. preterm NICU population. Further research is needed to understand what types of engagement are most salient, how they should be measured, and which immediate outcomes are the best predictors of long-term health and well-being.

1.

Introduction

Medicinal plants have been identified and used throughout human history [1]. In the past, people have attributed the healing of diseases using plants with medicinal properties to supernatural forces [2]. However, in recent years, medicinal plants have been tested extensively and found to have several pharmacological uses such as antibacterial, antifungal, antidiabetic, antioxidant, hepatoprotective, hemolytic, antiproliferative, anti-inflammatory, immunomodulatory, larvicidal, anthelmintic, central nervous system and analgesic activities [3,4].

Antioxidants act as free radical scavengers by terminating free radical chain reactions and inhibiting other oxidation reactions. They alleviate health problems such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes and cancer caused by oxidative damage. Antioxidants may also enhance immune defense, lowering the risk of cancer and infections [5]. They also have many industrial uses, such as use as preservatives in food and cosmetics and in preventing degradation of rubber and gasoline [6].

Helminths infections (helminthiasis) are a great health problem in humans and animals, causing considerable suffering and growth retardation. Also, in domestic animals, helminthic infections pose serious economic loss especially in areas where extensive grazing is practiced [7]. The disease is highly prevalent particularly in developing countries [8]. Anthelmintics or antihelminthics are drugs that expel parasitic worms from the body either by stunning or killing them [9]. The principal mode for control of gastrointestinal parasites today is based on commercial anthelmintics. Before 1940, only natural substances found to have some effects on parasites were used to treat parasitism, but there was risk of toxicity. The introduction of phenothiazine which was administered to sheep as a drench and/or included in salt mixtures highlighted the modern age of deworming. Effective anthelmintic drugs have selective toxic effects on the parasites causing helminthic infections.

Many side/secondary effects are associated with allopathic medicines, usually due to modes of leaving and emerging drug resistant microbes. Many people are now going "back-to-nature", using natural medicinal plants or natural health alternatives to prevent and treat diseases to counteract these side effects [10]. Studies on several plants have been done all over the world and plants have shown great potential in the treatment of diseases affecting both humans and animals [11].

The study plant, cocoa (Theobroma cacao L.), is a small evergreen tree belonging to the family Sterculiaceae. It has been used traditionally for treating various disorders such as anemia, malaria, mental fatigue, tuberculosis, fever, gout, as worm expeller and for wound healing [12,13,14].

Hence, this study aims to determine the antioxidant activities and anthelmintic properties of the aqueous and ethanolic extracts of the leaves of Theobroma cacao. Much scientific data needs to be provided to create the needed confidence in the use of medicinal plants that have been used since ancient times to treat illnesses.

2.

Materials and methods

2.1. Chemicals

Chemicals and reagents used in this study include ethanol, sulphuric acid (H2SO4), chloroform (CHCl3), acetic acid (CH3COOH), Folin Ciocalteu reagent, sodium carbonate (Na2CO3), gallic acid, trichloroacetic acid (TCA), sodium phosphate buffer, potassium hexacyanoferrate, ferric chloride (FeCl3), and Zentel. All chemicals used were of analytical grade.

2.2. Collection of plant

Cocoa leaves were randomly collected in a farmland at Ado-Ekiti, Nigeria and authenticated at the IFE herbarium, Department of Botany, Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile-Ife, Nigeria where a copy was deposited (voucher number: 62385). The leaves were air-dried and grinded to fine powder.

2.3. Preparation of extracts

Three extraction procedures were used: Aqueous (cold and hot extractions) and ethanolic extraction. For cold aqueous extraction, 200 g fine leaf powder was macerated with 1000 mL distilled water for 24 h. The mixture was filtered using Whatmann No. 1 filter paper. The filtrate obtained was lyophilized and stored at 4 ℃. For hot water extraction, 200 g fine leaf powder was mixed with 1000 mL distilled water in a 1 l flask. The mixture was boiled for 90 min at 90 ℃, cooled and filtered with Whatmann No. 1 filter paper. The filtrate obtained was lyophilized and stored at 4 ℃ until required. For ethanolic extraction, 200 g fine leaf powder was macerated in 1000 mL 95% ethanol for 16 h at room temperature. The mixture was filtered with glass wool. The filtrate obtained was lyophilized and stored at 4 ℃ until required. The lyophilized powders were reconstituted in distilled water for each experiment.

2.4. Collection of animals

African adult earthworms, which were collected from moist soil of Afe Babalola University, Ado-Ekiti and washed with normal saline to remove all fecal matter, were used for anthelmintic study. The earthworms (Pheretima posthuma) of 3–5 cm in length and 0.1–0.2 cm in width were used for all the experimental protocol due to its anatomical and physiological resemblance with the intestinal roundworm parasites of human beings.

2.5. Phytochemical screening

Phytochemical screening was done using standard procedures of Boye and Ampufo [15], Sofowora [16] and Banzouzi et al. [17] as modified by Swamy et al. [11]. To establish the presence of tannins, 0.5 g of the various extracts was put in a test tube and 20 mL of distilled water was added and heated to boiling. The mixture was filtered and 1% FeCl3 was added to the filtrate. Brownish green coloration indicated the presence of tannins. For saponins, 5 mL distilled water was added to each extract and vigorously shaken. Formation of a stable foam indicated the presence of saponins. To establish the presence of flavonoids, 5 mL dilute ammonia and 2 mL conc. H2SO4 were added to a portion of each extract in different test tubes. The appearance of a yellow color indicated the presence of flavonoids. The presence of terpenoids was investigated by the addition of 2 mL chloroform to the extracts in different test tubes and vigorously shaken. The mixture was evaporated to dryness. H2SO4 (2 mL) was added and heated for 2 min. A greyish color indicated the presence of terpenoids. The presence of glycosides was investigated with Salkowsk's test as follows. The extracts of the leaves of Theobroma cacao was mixed with 2 mL chloroform. Conc. H2SO4 (2 mL) was carefully added and the mixture was gently shaken. The presence of a steroidal ring (glycine portion of glycoside) was indicated by the formation of a red brown color. Liebermann Burchard reaction was used to investigate the presence of steroids. Two grams of each extract was put in test tubes and 10 mL chloroform was added and filtered. 2 mL of the filtrate was mixed with 2 mL of a mixture of acetic acid and conc. H2SO4, added along the side of the test tube. A blue green ring indicated the presence of steroids. The presence of phenol was investigated by adding few drops of 2% FeCl3 to the extracts. A blue-green or black coloration indicated the presence of phenols.

2.6. Determination of total phenol

The total phenol content of the extracts was determined by the method of Vermeris [18]. 0.1 mL of each extract was mixed with 2 mL of freshly prepared sodium carbonate (2%) and vigorously mixed. After 5 min, 100 μL Folin-Ciocalteu reagent (1 N) was added to the mixture and incubated for 30 min at room temperature. Absorbance was taken against blank at 750 nm. Gallic acid was used as the standard phenol at varying concentrations. The results were expressed as mg gallic acid equivalent per gram of dry extract (mg GAE/g).

2.7. Determination of ferric reducing property

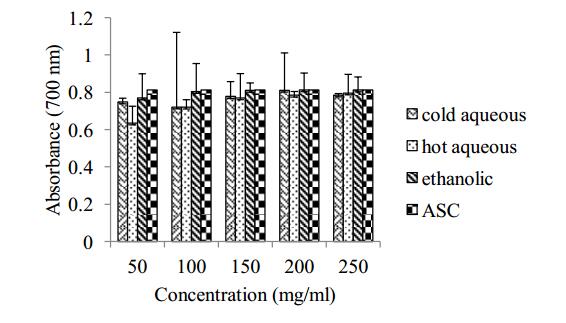

The reducing property of the extracts was determined according to the method of Pulido et al. [19]. 0.25 mL of extract was mixed with 0.25 mL of 200 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 6.6) and 0.25 mL 1% potassium ferricyanide. The mixture was incubated at 50 ℃ for 20 min. This was followed by the addition of 0.25 mL 10% tricarboxylic acid. The mixture was centrifuged at 2000 rpm for 10 min. 1 mL of supernatant was mixed with 1 mL of distilled water and 0.2 mL FeCl3. Absorbance was measure at 700 nm.

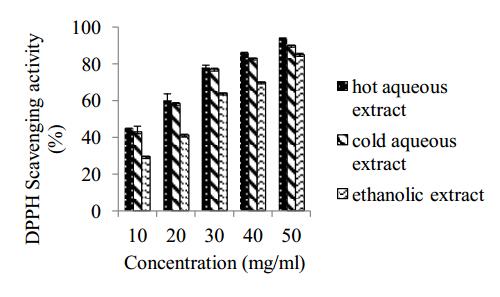

2.8. Determination of DPPH scavenging activity

DPPH radical scavenging activity was determined according to the method of Shimada et al. [20] with slight modification. An aliquot (1 mL) of 0.1 mM freshly prepared DPPH solution in methanol was added to 1 mL of each sample (10–50 mg/mL), the mixture was shaken vigorously and left in the dark at room temperature for 30 min. The absorbance of the resultant solution was measured at 517 nm. All determinations were performed in triplicates. The radical scavenging activities of the tested samples, expressed as percentage of inhibition were calculated according to the following formula:

where A0 is the value of DPPH without sample; A is the value of sample and DPPH; Ab is the value of sample without DPPH.

The lower the absorbance value, the higher the ability to scavenge DPPH free radicals. The 50% inhibitory concentration value (IC50) is indicated as the effective concentration of extract required to scavenge 50% of the radicals.

2.9. Anthelmintic screening

In vitro anthelmintic assay was performed on adult African earthworm (Pheretima posthuma) according to the method of Ajaiyeoba et al. [21] with slight modifications. Standard drug (albendazole) and different concentrations of aqueous and ethanolic extracts of cocoa leaves (10, 25 and 50 mg/mL) were prepared in distilled water and poured into well-labeled petri dishes (50 mL). Five worms of nearly equal sizes were introduced into each of the dishes. Observations were made for the time taken to paralysis and death of individual worm. Paralysis was said to occur when the worms were not able to move. Death was concluded when the worms lost their motility followed with fading away of their body color. Death was also confirmed by dipping the worms in slightly warm water. The mortality of parasite was assumed to have occurred when all signs of movement had ceased.

2.10. Statistical analysis

Results were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (n = 6). Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism software (Prism 5 for windows). One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Duncan's post hoc test was carried out to determine significant statistical differences. Differences were considered as significant with p < 0.05.

3.

Results and discussion

3.1. Phytochemical composition

Phytochemicals such as saponins, tannins, phenols and glycosides were present in the aqueous and ethanolic extracts of the leaves of Theobroma cacao. Flavonoids were only present in the ethanolic extracts. This might be because ethanol is a better extractant than water [22]. Terpenoids and steroids were absent in all the extracts (Table 1). Studies have shown that plant contain a large variety of plant chemicals or phytochemicals with antioxidant activity [23,24] with phenols and flavonoids contributing more [25].

3.2. Antioxidant activity

The result of total phenolic content is shown in Table 2. The total phenolic content of the ethanolic extract is significant and higher than the total phenolic content of the aqueous extracts. The results of ferric reducing power of the extracts are shown in Figure 1. The results of ferric reducing power all the extracts were comparable to that of ascorbic acid. Radical scavenging activities are important because of the deleterious damage caused by free radicals in biological systems. The result of DPPH scavenging activity is shown in Figure 2. All the extracts showed a dose dependent scavenging activity with the aqueous extracts of the leaves of Theobroma cacao having higher DPPH scavenging activity with IC50 of 11.76 mg/mL and 12.95 mg/mL for the hot and cold aqueous extracts respectively. The ethanolic extract was low in scavenging activity when compared with the aqueous extracts with IC50 of 24.35 mg/mL. This suggests that the aqueous extracts of the leaves of Theobroma cacao had better scavenging activity than the ethanolic extract. This result is different from the study of Das et al. [26] in which the ethanolic extract of the fruits of Momordica charantia had higher scavenging activity than the aqueous extract and, the ethanolic extract of Momordica dioica had higher free radical scavenging activity than its aqueous extract [27]. The free radical scavenging activity of the hot aqueous extract of T. cacao is higher than that of the cold aqueous extract. This is similar with the result obtained by Ansari et al. [28] in which hot extract of Momordica charantia possessed higher free radical scavenging activity than its cold extract.

Phenolics, which are secondary metabolites commonly found in medicinal plants, contribute to plants' antioxidant potential by neutralizing free radicals and preventing decomposition of hydroperoxides into free radicals. There is usually a positive correlation between phenolic contents and antioxidative ability. There are a number of methods to assay for phenolic content in plants, amongst which is the Folin-Ciocalteu's assay used in this study. The Folin-Ciocalteu's assay gives a crude estimate of total phenolic compounds present in a sample, however it is not specific to only polyphenols but also to many interfering compounds [29,30]. It is possible that the high phenolic content observed for the ethanolic extract of T. cacao in this study was as a result of interfering contents in the extract and thus the low DPPH scavenging activity it exhibited.

3.3. Anthelmintic property

Helminth infections in humans and animals and treatment have been of great concern to the medical field for centuries. Parasitic helminths usually cause a chronic and debilitating disease in humans and animals, leading to death, especially in developing countries [26]. Despite many advances in understanding the mode of transmission and treatment of helminths, there are still limitations to treating helminthic infections. Also, due to indiscriminate use of anthelmintic substances, there have been cases of resistance of helminths. Because of this, plants used to treat helminthic infections traditionally are now studied for anthelmintic activities. The result of anthelmintic property of extracts of Threoboma cacao is shown in Table 3. All the extracts showed potent activity at the highest concentration (50 mg/mL) used against earthworms. All the extracts showed high anthelmintic effect, with the ethanolic extract exhibiting the highest activity even at low concentration (10 mg/mL) when compared to the standard. The extracts exhibited activity in a dose dependent manner varying from loss of motility to loss of response to external stimuli, which eventually advanced to death. The ethanolic extract had significant higher anthelmintic effect (p < 0.05) when compared to the other extracts and standard drug (albendazole). At 50 mg/mL, the ethanolic extract showed less time for paralysis to occur (10 ± 0.15 min) and eventually death (16 ± 1.15 min) of the earthworms. The aqueous extracts, on the other hand had significant lower anthelmintic activity (p < 0.05) when compared to the standard drug, albendazole and ethanolic extracts. However, the extracts prepared with hot water extraction had higher anthelmintic activities than those prepared with cold water extraction. All the extracts of Threoboma cacao in this study displayed similar mode of action with the anthelminthic drug, albendazole, which usually causes paralysis of worms and their subsequent expulsion in the feaces of humans and animals [31].

Phytochemicals such as tannins and phenols which were revealed in the aqueous and ethanolic extracts of Threoboma cacao are known to exhibit anthelmintic property by interfering with energy generation in helminth parasites, uncoupling oxidative phosphorylation, and binding to free proteins in the gastrointestinal tract of host animal or glycoprotein on the cuticle of the parasite, leading to death [32,33]. It is therefore possible that the anthelmintic effect exhibited by the aqueous and ethanolic extracts of T. cacao is due to the presence tannins, phenols and flavonoids in the extract.

4.

Conclusion

The present study revealed that the extracts of the leaves of T. cacao has significant antioxidant and anthelmintic activities, confirming its use in traditional medicine. Thus, the leaves of Theobroma cacao can be viewed as a potential natural source of antioxidants and antihelminthics.

Conflict of interest

All authors declare no conflict of interest in this paper.

DownLoad:

DownLoad: