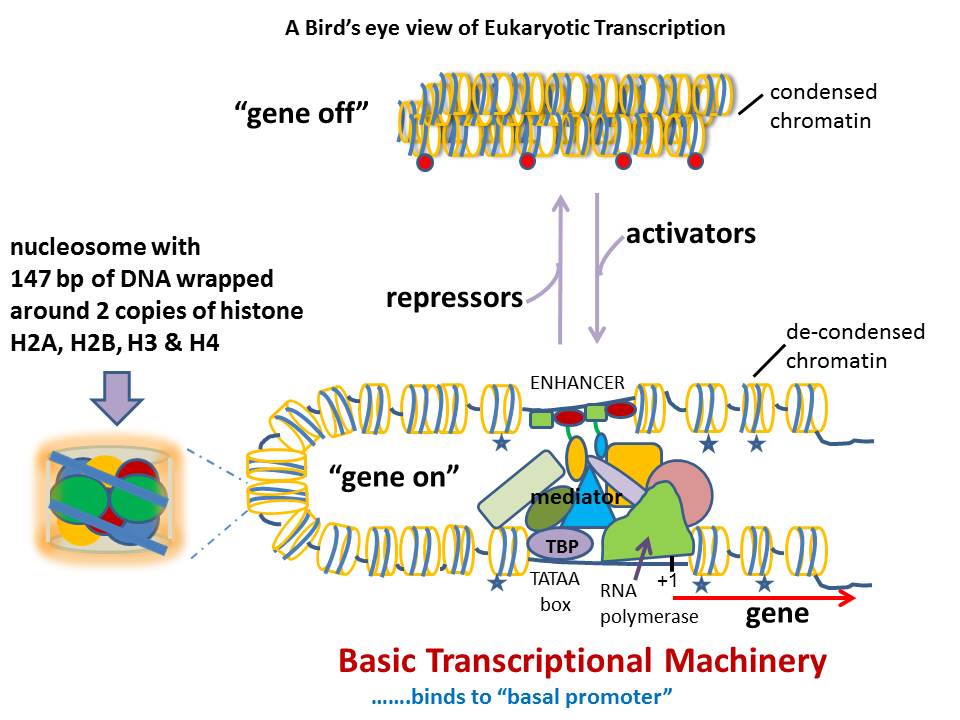

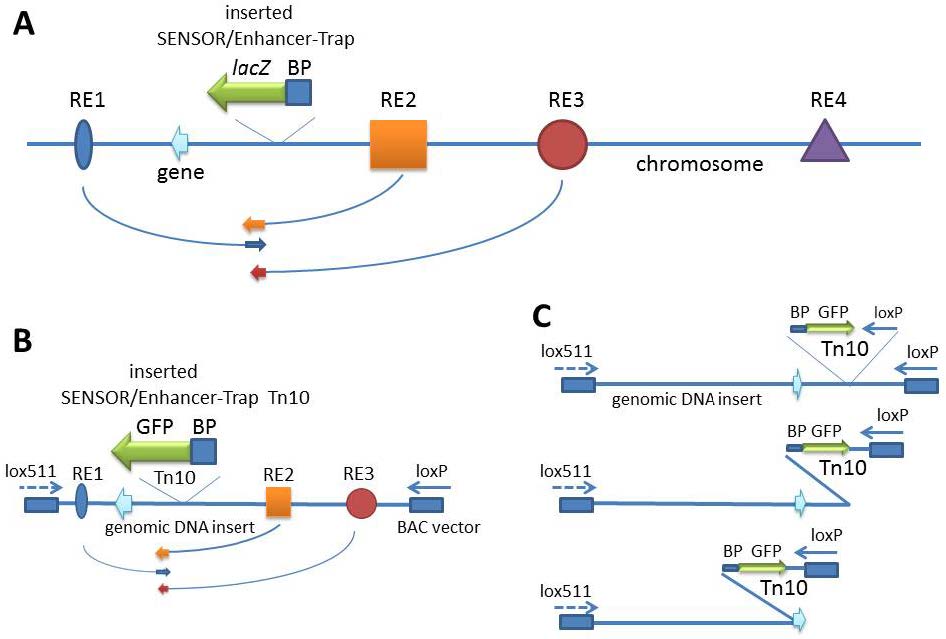

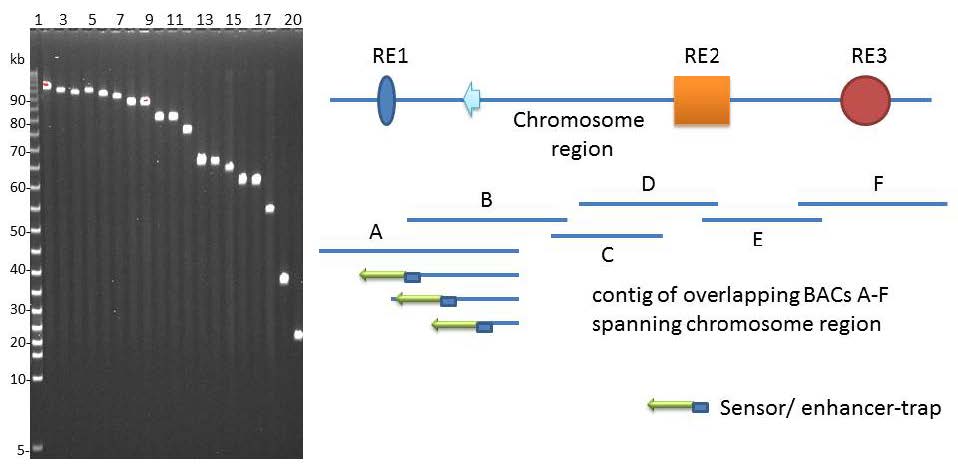

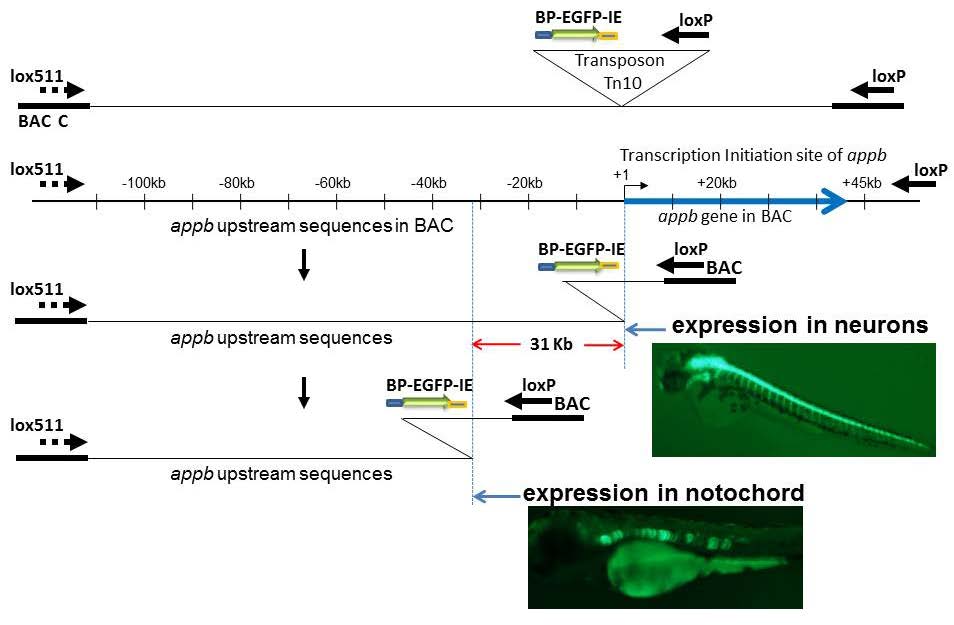

There is renewed interest in understanding expression of vertebrate genes in their chromosomal context because regulatory sequences that confer tissue-specific expression are often distributed over large distances along the DNA from the gene. One approach inserts a universal sensor/reporter-gene into the mouse or zebrafish genome to identify regulatory sequences in highly conserved non-coding DNA in the vicinity of the integrated reporter-gene. However detailed mechanisms of interaction of these regulatory elements among themselves and/or with the genes they influence remain elusive with the strategy. The inability to associate distant regulatory elements with the genes they regulate makes it difficult to examine the contribution of sequence changes in regulatory DNA to human disease. Such associations have been obtained in favorable circumstances by testing the regulatory potential of highly conserved non-coding DNA individually in small reporter-gene-containing plasmids. Alternative approaches use tiny fragments of chromosomes in Bacterial Artificial Chromosomes, BACs, where the gene of interest is tagged in vitro with a reporter/sensor gene and integrated into the germ-line of animals for expression. Mutational analysis of the BAC DNA identifies regulatory sequences. A recent approach inserts a sensor/reporter-gene into a BAC that is also truncated progressively from an end of genomic insert, and the end-deleted BAC carrying the sensor is then integrated into the genome of a developing animal for expression. The approach allows mechanisms of tissue-specific gene expression to be explored in much greater detail, although the chromosomal context of such mechanisms is limited to the length of the BAC. Here we discuss the relative strengths of the various approaches and explore how the integrated-sensor in the BACs method applied to a contig of BACs spanning a chromosomal region is likely to address mechanistic questions on interactions between gene and regulatory DNA in greater molecular detail.

1.

Introduction and statement of the results

Cloaking using transformation optics (changes of variables) was introduced by Pendry, Schurig and Smith [30] for the Maxwell system and by Leonhardt [16] in the geometric optics setting. These authors used a singular change of variables, which blows up a point into a cloaked region. The same transformation had been used to establish (singular) non-uniqueness in Calderon's problem in [10]. To avoid using the singular structure, various regularized schemes have been proposed. One of them was suggested by Kohn, Shen, Vogelius and Weinstein [11], where instead of a point, a small ball of radius $ \varepsilon $ is blown up to the cloaked region. Approximate cloaking for acoustic waves has been studied in the quasistatic regime [11,26], the time harmonic regime [12,19,27,20], and the time regime [28,29], and approximate cloaking for electromagnetic waves has been studied in the time harmonic regime [4,14,24], see also the references therein. Finite energy solutions for the singular scheme have been studied extensively [9,32,33]. There are also other ways to achieve cloaking effects, such as the use of plasmonic coating [2], active exterior sources [31], complementary media [13,22], or via localized resonance [23] (see also [17,21]).

The goal of this paper is to investigate approximate cloaking for the heat equation using transformation optics. Thermal cloaking via transformation optics was initiated by Guenneau, Amra and Venante [8]. Craster, Guenneau, Hutridurga and Pavliotis [6] investigate the approximate cloaking for the heat equation using the approximate scheme in the spirit of [11]. They show that for the time large enough, the largeness depends on $ \varepsilon $, the degree of visibility is of the order $ \varepsilon^d $ ($ d = 2, 3 $) for sources that are independent of time. Their analysis is first based on the fact that as time goes to infinity, the solutions converge to the stationary states and then uses known results on approximate cloaking in the quasistatic regime [11,26].

In this paper, we show that approximate cloaking is achieved at any positive time and established the degree of invisibility of order $ \varepsilon $ in three dimensions and $ |\ln \varepsilon|^{-1} $ in two dimensions. Our results hold for a general source that depends on both time and space variables, and our estimates depend only on the range of the materials inside the cloaked region. The degree of visibility obtained herein is optimal due to the fact that a finite time interval is considered (compare with [6]). The analysis in this paper is of frequency type via Fourier transform with respect to time. This approach is robust and can be used in different context. A technical issue is on the blow up of the fundamental solution of the Helmholtz type equations in two dimensions in the low frequency regime. We emphasize that even though our setting is in a bounded domain, we employs Fourier transform in time instead of eigenmodes decomposition. This has the advantage that one can put the non-perturbed system and the cloaking system in the same context.

We next describe the problem in more detail and state the main result. Our starting point is the regularization scheme [11] in which a transformation blows up a small ball $ B_\varepsilon $ ($ 0 < \varepsilon < 1/2 $) instead of a point into the cloaked region $ B_1 $ in $ \mathbb{R}^d $ ($ d = 2, 3 $). Here and in what follows, for $ r > 0 $, $ B_r $ denotes the ball centered at the origin and of radius $ r $ in $ \mathbb{R}^d $. Our assumption on the geometry of the cloaked region is mainly to simplify the notations. Concerning the transformation, we consider the map $ F_{\varepsilon}: {\mathbb{R }}^d \rightarrow {\mathbb{R }}^d $ defined by

In what follows, we use the standard notations

for the "pushforward" of a symmetric, matrix-valued function $ A $, and a scalar function $ \rho $, by the diffeomorphism $ F $, and $ I $ denotes the identity matrix. The cloaking device in the region $ B_2 \setminus B_1 $ constructed from the transformation technique is given by

a pair of a matrix-valued function and a function that characterize the material properties in $ B_2 \setminus B_1 $. Physically, this is the pair of the thermal diffusivity and the mass density of the material.

Let $ \Omega $ with $ B_2 \Subset \Omega \subset \mathbb{R}^d $ ($ d = 2, 3 $)* be a bounded region for which the heat flow is considered. Suppose that the medium outside $ B_2 $ (the cloaking device and the cloaked region) is homogeneous so that it is characterized by the pair $ (I, 1) $, and the cloaked region $ B_1 $ is characterized by a pair $ (a_O, \rho_O) $ where $ a_O $ is a matrix-valued function and $ \rho_O $ is a real function, both defined in $ B_{1} $. The medium in $ \Omega $ is then given by

*The notation $ D \Subset \Omega $ means that the closure of $ D $ is a subset of $ \Omega $.

In what follows, we make the usual assumption that $ a_O $ is symmetric and uniformly elliptic and $ \rho_O $ is a positive function bounded above and below by positive constants, i.e., for a.e. $ x \in B_{1} $,

and

for some $ \Lambda \ge 1 $. Given a function $ f \in L^1 \big((0, + \infty), L^2(\Omega) \big) $ and an initial condition $ u_0 \in L^2(\Omega) $, in the medium characterzied by $ (A_c, \rho_c) $, one obtains a unique weak solution $ u_c \in L^2\big((0, \infty); H^1(\Omega)\big) $ $ \cap C \big([0, + \infty); L^2(\Omega) \big) $ of the system

and in the homogeneneous medium characterized by $ (I, 1) $, one gets a unique weak solution $ u \in L^2\big((0, \infty); H^1(\Omega) \big) \cap C \big([0, + \infty); L^2(\Omega) \big) $ of the system

The approximate cloaking meaning of the scheme (1.4) is given in the following result:

Theorem 1.1. Let $ u_0 \in L^2(\Omega) $ and $ f \in L^1\big((0, + \infty); L^2(\Omega) \big) $ be such that $ \operatorname{supp} u_0, \, \operatorname{supp} f(t, \cdot) \subset \Omega \setminus B_2 $ for $ t > 0 $. Assume that $ u_c $ and $ u $ are the solution of (1.7) and (1.8) respectively. Then, for $ 0 < \varepsilon < 1/2 $,

for some positive constant $ C $ depending on $ \Lambda $ but independent of $ f $, $ u_0 $, and $ \varepsilon $, where

As a consequence of Theorem 1.1, $ \lim_{\varepsilon \to 0} u_c (t, \cdot) = u (t, \cdot) $ in $ (0, + \infty) \times (\Omega \setminus B_2) $ for all $ f $ with compact support outside $ (0, +\infty) \times B_2 $ and for all $ u_0 $ with compact support outside $ B_2 $. One therefore cannot detect the difference between $ (A_c, \rho_c) $ and $ (I, 1) $ as $ \varepsilon \rightarrow 0 $ by observation of $ u_c $ outside $ B_2 $: Cloaking is achieved for observers outside $ B_2 $ in the limit as $ \varepsilon \rightarrow 0 $.

We now briefly describe the idea of the proof. The starting point of the analysis is the invariance of the heat equations under a change of variables which we now state.

Lemma 1.1. Let $ d \ge 2 $, $ T > 0 $, $ \Omega $ be a bounded open subset of $ \mathbb{R}^d $ of class $ C^1 $, and let $ A $ be an elliptic symmetric matrix-valued function, and $ \rho $ be a bounded, measurable function defined on $ \Omega $ bounded above and below by positive constants. Let $ F: \Omega \mapsto \Omega $ be bijective such that $ F $ and $ F^{-1} $ are Lipschitz, $ \det \nabla F > c $ for a.e. $ x \in \Omega $ for some $ c > 0 $, and $ F(x) = x $ near $ \partial \Omega $. Let $ f \in L^1\big((0, T); L^2(\Omega) \big) $ and $ u_0 \in L^2(\Omega) $. Then $ u \in L^2\big((0, T); H^1_0(\Omega) \big) \cap C\big([0, T); L^2(\Omega) \big) $ is the weak solution of

if and only if $ v(t, \cdot): = u (t, \cdot) \circ F^{-1} \in L^2\big((0, T); H^1_0(\Omega) \big) \cap C\big([0, T); L^2(\Omega) \big) $ is the weak solution of

Recall that $ F_* $ is defined in (1.2). In this paper, we use the following standard definition of weak solutions:

Definition 1.1. Let $ d \ge 2 $ and $ T > 0 $. We say a function

is a weak solution to (1.9) if $ u(0, \cdot) = u_0 \mbox{ in } \Omega $ and $ u $ satisfies

in the distributional sense for all $ \varphi \in H^1_0(\Omega) $.

The existence and uniqueness of weak solutions are standard, see, e.g., [1] (in fact, in [1], $ f $ is assumed in $ L^2\big((0, T); L^2(\Omega) \big) $, however, the conclusion holds also for $ f \in L^1\big((0, T); L^2(\Omega) \big) $ with a similar proof, see, e.g., [25]). The proof of Lemma 1.1 is similar to that of the Helmholtz equation, see, e.g., [12] (see also [6] for a parabolic version).

We now return to the idea of the proof of Theorem 1.1. Set

Then $ u_\varepsilon $ is the unique solution of the system

where

Moreover,

In comparing the coefficients of the systems verified by $ u $ and $ u_\varepsilon $, the analysis can be derived from the study of the effect of a small inclusion $ B_\varepsilon $. The case in which finite isotropic materials contain inside the small inclusion was investigated in [3] (see also [5] for a related context). The analysis in [3] partly involved the polarization tensor information and took the advantage of the fact that the coefficients inside the small inclusion are finite. In the cloaking context, Craster et al. [6] derived an estimate of the order $ \varepsilon^d $ for a time larger than a threshold one. Their analysis is based on long time behavior of solutions to parabolic equations and estimates for the degree of visibility of the conducting problem, see [11,26], hence the threshold time goes to infinity as $ \varepsilon \to 0 $.

In this paper, to overcome the blow up of the coefficients inside the small inclusion and to achieve the cloaking effect at any positive time, we follow the approach of Nguyen and Vogelius in [28]. The idea is to derive appropriate estimates for the effect of small inclusions in the time domain from the ones in the frequency domain using the Fourier transform with respect to time. Due to the dissipative nature of the heat equation, the problem in the frequency for the heat equation is more stable than the one corresponding to the acoustic waves, see, e.g., [27,28], and the analysis is somehow easier to handle in the high frequency regime. After using a standard blow-up argument, a technical point in the analysis is to obtain an estimate for the solutions of the equation $ \Delta v + i \omega \varepsilon^2 v = 0 $ in $ \mathbb{R}^d \setminus B_1 $ ($ \omega > 0 $) at the distance of the order $ 1/\varepsilon $ in which the dependence on $ \varepsilon $ and $ \omega $ are explicit (see Lemma 2.2). Due to the blow up of the fundamental solution in two dimensions, the analysis requires new ideas. We emphasize that even though our setting is in a bounded domain with zero Dirichlet boundary condition, we employs Fourier transform in time instead of eigenmodes decomposition as in [6] to put both systems of $ u_\varepsilon $ and $ u $ in the same context.

2.

Proof of the main result

To implement the analysis in the frequency domain, let us introduce the Fourier transform with respect to time $ t $:

for $ \varphi \in L^2((-\infty, + \infty), L^2(\mathbb{R}^d)) $. Extending $ u, \, u_c $, $ u_\rho $ and $ f $ by $ 0 $ for $ t < 0 $, and considering the Fourier with respect to time at the frequency $ \omega > 0 $, we obtain

and

where

The main ingredient in the proof of Theorem 1.1 is the following:

Proposition 2.1. Let $ \omega > 0 $, $ 0 < \varepsilon < 1/2 $, and let $ g \in L^2(\Omega) $ with $ \operatorname{supp} g \subset \Omega \setminus B_2 $. Assume that $ v, \, v_\varepsilon \in H^1(\Omega) $ are respectively the unique solution of the systems

and

We have

for some positive constant $ C $ independent of $ \varepsilon $, $ \omega $ and $ g $. Here

and

The rest of this section is divided into three subsections. In the first subsection, we present several lemmas used in the proof of Proposition 2.1. The proofs of Proposition 2.1 and Theorem 1.1 are then given in the second and the third subsections, respectively.

2.1. Preliminaries

In this subsection, we state and prove several useful lemmas used in the proof of Proposition 2.1. Throughout, $ D \subset B_1 $ denotes a smooth, bounded, open subset of $ \mathbb{R}^d $ such that $ \mathbb{R}^d \setminus D $ is connected, and $ \nu $ denotes the unit normal vector field on $ \partial D $, directed into $ \mathbb{R}^d \setminus D $.

The first result is the following simple one:

Lemma 2.1. Let $ d = 2, \, 3 $, $ k > 0 $, and let $ v \in H^1 ({\mathbb{R }}^d \setminus D) $ be such that $ \Delta v +i k v = 0 $ in $ \mathbb{R}^d \setminus D $. We have, for $ R > 2 $,

for some positive constants $ C_R $ independent of $ k $ and $ v $.

Proof. Multiplying the equation by $ \bar v $ (the conjugate of $ v $) and integrating by parts, we have

This implies

Here and in what follows, $ C $ denotes a positive constant independent of $ v $ and $ k $. Since $ \Delta v = - i k v $ in $ B_2 \setminus D $, by the trace theory, see, e.g., [7,Theorem 2.5], we have

Combining (2.6) and (2.7) yields

The conclusion follows when $ k \ge 1 $.

Next, consider the case $ 0 < k < 1 $. In the case where $ d = 3 $, the conclusion is a direct consequence of (2.8) and the Hardy inequality (see, e.g., [18,Lemma 2.5.7]):

We next consider the case where $ d = 2 $. One just needs to show

By the Hardy inequality (see, e.g., [18,Lemma 2.5.7]),

it suffices to prove (2.10) for $ R = 2 $ by contradiction. Suppose that there exists a sequence $ (k_n) \to 0 $ and a sequence $ (v_n) \in H^1(\mathbb{R}^2 \setminus D) $ such that

Denote

By (2.8) and (2.11), one might assume that $ v_n $ converges to $ v $ weakly in $ H^1_{ \operatorname{loc }}(\mathbb{R}^2 \setminus D) $ and strongly in $ L^2(B_2 \setminus D) $. Moreover, $ v \in W^1(\mathbb{R}^2 \setminus D) $ and $ v $ satisfies

and

From (2.12), we have $ v = 0 $ in $ \mathbb{R}^2 \setminus D $ (see, e.g., [18]) which contradicts (2.13). The proof is complete.

We also have

Lemma 2.2. Let $ d = 2, 3 $, $ \omega > 0 $, $ 0 < \varepsilon < 1/2 $, and let $ v \in H^1 ({\mathbb{R }}^d \setminus D) $ be a solution of $ \Delta v +i\omega \varepsilon^2 v = 0 $ in $ \mathbb{R}^d \setminus D $. We have, for $ 3/2 < |x| < R $,

for some positive constant $ C = C_{R} $ independent of $ \varepsilon $, $ \omega $ and $ v $.

Recall that $ e(\varepsilon, \omega, d) $ is given in (2.3) and (2.4).

Proof. By the trace theory and the regularity theory of elliptic equations, we have

It follows from Lemma 2.1 that

Here and in what follows in this proof, $ C $ denotes a positive constant depending only on $ R $ and $ D $.

The representation formula gives

where $ \ell = e^{i \pi/4} \varepsilon \omega^{1/2} $, and, for $ x \neq y $,

Here $ H^{(1)}_0 $ is the Hankel function of the first kind of order 0. Recall, see, e.g., [15,Chapter 5], that

and

We now consider the case $ d = 3 $. We have, for $ 3/2 < |x| < R $ and $ y \in \partial B_{2} $,

It follows that, for $ 3/2 < |x| < R $ and $ y \in \partial B_{2} $,

Similarly, one has, for $ 3/2 < |x| < R $ and $ y \in \partial B_{2} $,

Combining (2.17), (2.20) and (2.21) yields

We derive from (2.16) that

which is the conclusion in the case $ d = 3 $.

We next deal with the case where $ d = 2 $ and $ \omega > \varepsilon^{-2}/4 $, which is equivalent to $ |\ell| > 1/2 $. From (2.19), we derive that, for $ 3/2 < |x| < R $ and $ y \in \partial B_{2} $,

Using (2.16) and combining (2.17) and (2.22), we obtain, since $ \omega > \varepsilon^{-2}/4 $,

which gives the conclusion in this case.

We finally deal with the case where $ d = 2 $ and $ 0 < \omega < \varepsilon^{-2}/4 $, which is equivalent to $ |\ell| < 1/2 $. From (2.17), we obtain, for $ x \in \partial B_{4} $,

Since $ d = 2 $, we have

It follows from Lemma 2.1 and the trace theory that

Since, by (2.18),

and

we derive from (2.23) and (2.24) that

Again using (2.17), we get, for $ 3/2 < |x| < R $,

Since, by (2.18), for $ 0 < \omega < 1/2 $,

and, by (2.19), for $ 1/2 < \omega < \varepsilon^{-2}/4 $,

we derive from (2.24), (2.25) and (2.26) that, for $ 3/2 < |x| < R $,

which yields the conclusion in the case $ 0 < \omega < \varepsilon^{-2}/4 $. The proof is complete.

2.2. Proof of Proposition 2.1

In this proof, $ C $ denotes a positive constant depending only on $ \Omega $ and $ \Lambda $. Multiplying the equation of $ v_\varepsilon $ by $ \bar v_\varepsilon $ and integrating in $ \Omega $, we derive that

Here we used Poincaré's inequality

It follows from (2.27) that

Similarly, using the equation for $ v $ and Poincaré's inequality, we get

Since $ \Delta v+i\omega v = 0 $ in $ B_2 $, using Caccioppolli's inequality, we have

By Sobolev embedding, as $ d\le 3 $,

It follows that

Set

Then $ w_{\varepsilon} \in H^1(\Omega \setminus B_\varepsilon) $ and satisfies

Let $ \widetilde w_{\varepsilon}\in H^1(\mathbb{R}^d \setminus B_{\varepsilon}) $ be the unique solution of the system

and set

Then $ \widetilde W_{\varepsilon} \in H^1(\mathbb{R}^d \setminus B_{1}) $ is the unique solution of the system

Fix $ r_0 > 2 $ such that $ \Omega \subset B_{r_0} $. By Lemma 2.2, we have, for $ 1 \le |x| < r_0 $, that

which yields, for $ x \in B_{r_0} \setminus B_{1} $, that

Since $ \Delta \widetilde w_{\varepsilon} + i \omega \widetilde w_{\varepsilon} = 0 $ in $ B_{r_0} \setminus B_{1} $, it follows from Caccioppoli's inequality that

Fix $ \varphi \in C^2(\mathbb{R}^d) $ such that $ \varphi = 1 $ in $ B_{3/2} $ and $ \varphi = 0 $ in $ \mathbb{R}^d \setminus B_2 $, and set

Then $ \chi_{\varepsilon}\in H^1_0(\Omega \setminus B_\varepsilon) $ and satisfies

Multiplying the equation of $ \chi_{\varepsilon} $ by $ \bar \chi_{\varepsilon} $ and integrating by parts, we obtain, by Poincaré's inequality,

Combining (2.36) and (2.37) yields

The conclusion now follows from (2.28) and (2.32).

2.3. Proof of Theorem 1.1

Let $ v_\varepsilon = u_\varepsilon - u $. Using the fact that $ v_\varepsilon $ is real, by the inversion theorem and Minkowski's inequality, we have, for $ t > 0 $,

Using Proposition 2.1, we get

It follows from (2.39) that, for $ t > 0 $,

Similarly, we have, for $ t > 0 $,

The conclusion follows.

Acknowledgments

The second author is funded by the Vietnam National Foundation for Science and Technology Development (NAFOSTED) under grant number 101.02-2015.21.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest in this paper.

DownLoad:

DownLoad: