1. Introduction

Distributed Generation (DG) plants are defined as a range of small-scale and modular devices designed to provide electricity in locations close to consumers and they can incorporate both fossil and renewable sources including wind, solar photovoltaic (PV), micro turbines, fuel cells, and other means of renewable energy [1]. Cities and communities across the nation are implementing such systems for the means of electricity generation from clean sources. However, many factors can influence the adoption of DG systems including governmental policies at the local, state, and federal levels, and project costs, which can vary given the time, location, size, and application types [2]. In 2009, San Antonio’s Energy Board adopted a Sustainable Energy Policy Statement that specifically endorsed the transition from a centralized power model to a DG model in an attempt to bring more solar to their community and to help alleviate the negative externalities from fossil fuel combustion [3]. California’s Solar Initiative Program (CSI) is a solar rebate plan for consumers of electricity within the participating energy provider’s territories, which funds solar systems on existing homes, commercial, governmental, agricultural, and non-profit buildings [4]. The energy providers, Pacific Gas and Electric, Southern California Edison, and San Diego Gas and Electric, provide nearly 70 percent of California’s electric load. The CSI has a budget of $2.167 billion that will be distributed over the next 10 years to support solar installs and is administered by the California Public Utilities Commission [4]. The funds are allocated among three programs; the CSI, the Multifamily Affordable Solar Housing Program (MASH) and the Single-Family Affordable Solar Homes (SASH) programs. Individuals or businesses that install systems are offered different incentive levels based on the performance of their solar panels. Even with cities across the country adopting DG programs and legislation, the costs for consumers may still be the deciding factors for installing a PV system. Here we suggest different payment options for these potential residential and small commercial customers in order to show how they could best afford a system. We also examine and report the jobs and economic impact of DG PV system implementation in the case study area.

2. Background

2.1. Funding and Payment Options for Distributed Generation Systems

Although the costs of residential or small business PV systems can be a factor that pushes prospective clients away, initiatives set forth by local and federal governments are driving these costs down. For example, the Department of Energy’s (DOE) Solar Sunshot Initiative have been supporting the research, design, and implementation of low-cost, high efficiency PV technologies in order to make solar electricity cost-competitive with other sources by 2020 [1]. Even with the DOE’s aggressive approach, the cost of a PV system can still be a burden on many prospective owners. The median installed price was $4.3/W for residential systems in 2014 [5]; thus the cost of a system becomes a large investment for most systems. SunShot’s objective is to have the cost of residential systems down to $1.50/W by the year 2020 [6]. To help alleviate this burden, new and unique payment plans are being designed to accommodate individuals depending on various factors including their income levels. Solar Powering Your Community: A Guide for Local Governments [7] provides a list of funding options that an individual or an entire community can investigate in order to mitigate the costs. With prices of PV technology expected to decrease in future years, expected payback periods should also decrease, resulting in an overall shorter payback period for PV systems. In 2007 the Department of Energy chose the Northeast Denver Housing Center (NDHC) as a pilot program for the Solar America Showcase program. The intent of this pilot program was to set up a model for the creation of a new residential finance model for the installation of PV systems in low-income residential areas. The program had to incorporate a low-income training program for residents in that area, an energy conservation incentive program, and a program for integration of renewable energy systems onto existing affordable housing developments [8]. The housing units that received systems were very low-income families who generally earned less than 60% of the median income ($36,480). In order to afford this program the NDHC established a power purchase agreement with a third-party investor with funds received from Colorado’s Governor’s Energy Office. The NDHC will purchase power from the third-party for a 20 year term in which they will pay $.08/kWh for the first year, and then prices will escalate at a rate of 5% per year for the term of the agreement [8]. In order to pay for the systems installed in the low-income areas, the NDHC charged tenants an increase of $25 per month on their electricity bill; however, the tenants will receive a decreased utility cost to cover the natural gas portion of their monthly energy expenses. Another stipulation of the pilot program included job training and tenant education for the low-income residents. This type of renewable energy financing programs drives the price of a PV system down, which can make it affordable for residential and commercial clients alike. The payment options presented in this paper are ones that are currently available to customers in Illinois. Recommendations for options available outside of Illinois will be presented in the discussion section. Payments options currently available include the following and they are summarized in Table 1

Table 1. Solar Financing Options and Schemes.

| Funding and Payment Options (PPA) | Financing Schemes |

| Power Purchase Agreement | · A third-party developer owns, operates, and maintains |

| · A host customer agrees to site the system on their property |

| · Allows the customer to buy electricity at a set cost for a given with no upfront cost |

| Community Solar | · Provides electricity to a defined community but the system itself does not have to be directly on rooftops |

| · Increase the access to solar for whom cannot install solar on their property such as a residence in shaded areas, rental properties, and multi-unit housing |

| Out-of-pocket Purchase | · Property owner responsible for financing the system |

| · Benefits include financial gains through renewable energy credits, investment returns, and insurance against increased electricity rates |

| Property Assessed Clean Energy Financing (PACE) | · A finance method to address the upfront cost |

| · Provides a long-term fixed cost financing option, a repayment obligation that can transfer, and federal tax benefits |

| Rural Energy for American Program (REAP) | · Financial assistance to agricultural producers and to small businesses in rural America |

| · Provides guaranteed loans and grants |

2.1.1. Power Purchase Agreement (PPA)

A power purchase agreement (PPA) is a financial agreement in which a third-party developer owns, operates, and maintains the PV system, and a host customer agrees to site the system on their roof or elsewhere on their property, and also agrees to purchase the PV systems electric output for a predetermined period [9]. The main benefit of a PPA is that it allows the customer to buy electricity at a set cost a given number of years, which provides insurance against fluctuating energy prices during those years. Another main benefit is that there is no upfront cost for the customer. The third-party provides all funding for the system and is responsible for any maintenance issues during the duration of their agreement. Once the agreement is over, the customer and third-party have the option to renew the agreement, the customer can purchase the system at its value, or the third party must remove the system from the customer’s property. This option is suitable for any income level, however it is especially appropriate for lower income levels, as no upfront cost is required.

2.1.2. Community Solar

Community solar, also called shared solar is defined as a solar PV system that, through a defined voluntary program, provides power and/or financial benefits [10]. A major benefit for community-owned solar is that it provides electricity to a defined community, but the system itself does not have to be directly on the rooftops of the residences within that community. In fact, a study by NREL in 2008 found that only 22 to 27% of residential rooftop areas are suitable for hosting an on-site PV system [10]. NREL has provided three alternative models for community solar as listed below:

• Utility Sponsored Systems, in which a utility owns and operates the system that is open to voluntary ratepayer participation.

• Buy a Brick wherein community members contribute to a community owned installation, and are allocated a percent of the electricity that is generated.

• Special Purpose Entity model (SPE) in which individual investors join a business enterprise to develop a community solar project.

One major benefit to community solar is that it can increase the access to solar electricity for those members who cannot install solar on their property. This would include a residence in shaded areas, where rooftop or ground mount systems are not suitable; it would also include rental properties and multi-unit housing where residents are not the owner of the property. There are at least 31 shared/community owned renewable projects in 12 different states throughout the U.S [11].

2.1.3. Out-of-pocket purchase

In the case of an out-of-pocket purchase, homeowners and business owners would be responsible for the entire payment of the PV system. Benefits of this option include sole ownership of the system. Benefits would additionally include any financial gains that the system may bring in such as Solar Renewable Energy Credits, investment returns once the system is paid off, and insurance against increased electricity rates in the future. However, since the owners are responsible for the system, they must pay for any maintenance or system problems costs. In some states the use of a direct incentive or production-based incentive such as a cash rebate has been used to lower the cost of the system for out-of-pocket purchases. These grants and rebates are often based on solar system capacity or system cost [12]. Along with 23 other states, Illinois is one of the states that have direct cash incentives for PV systems [12].

2.1.4. Property Assessed Clean Energy Financing (PACE)

The PACE program is a finance method used for renewable energy and energy-efficient investments; it is meant to address both the upfront cost barriers to solar and the hesitancy of homeowners to make long-term investments in their homes [12]. The way the PACE program works is that the city or county finances the upfront cost of the energy investment, either directly or intermittently for the private investors. The property owner then repays the loan over an extended period through a special property tax assessment. The main benefits of the PACE program are it provides a long-term fixed cost financing option, a repayment obligation that can transfer with the sale of the property, and the potential to deduct the loan interest from federal taxable income as part of a local property tax deduction. An example is in Boulder, Colorado, where PACE provided $40 million in bonds to offer special financing options for renewable energy and energy-efficient improvements to local residents. The loan to each resident is repaid over 15 years, and the key requirement of the agreement is that applicants must attend a workshop to learn about the program requirements and to receive information on the benefits of investing in energy efficiency measures [12]. Illinois has enacted PACE enabling legislation, and there is growing interest in developing programs for customers [13].

2.1.5. Rural Energy for America Program (REAP)

Similar to PACE, REAP is a program that provides financial assistance to agricultural producers and to small businesses in rural America to purchase, install, and construct renewable energy systems [14]. REAP provides guaranteed loans and grants to assist qualified applicants. With this type of loan, small businesses within the designated boundary would be qualified for the grants and loans, which would cover up to 75% of the total eligibleproject costs; and then the Renewable Energy System Grant could additionally cover up to 25% of the eligible cost.

2.2. Economic Impacts of DG systems

The Solar Foundation reports that as of a November 2014, there were 173,807 solar jobs in the United States [15], an increase of roughly 31,000 positions from previous year. Solar jobs are defined as workers who spend at least 50% of their time supporting solar-related activities. The Solar Foundation predicts positive industry growth for the next 12 months; specifically, it predicts a growth of 21.8% during that time period, compared to the overall economy, which is expected to grow at a rate of 1.1%. For those categorized as solar workers, the median average salary for installer was between $20-24 per hour, making it competitive with pay for related positions that require work experience; however no advanced educational degree is needed. Croucher [16] performed an economic impact study of installing solar PV Systems in each of the U.S. states. Using the same modeling software (National Renewable Energy Laboratory’s (NREL) Jobs and Economic Development Impact (JEDI)) as this present study, software from the he determined which state derives the greatest statewide economic impact for a given amount of solar deployment [16]. JEDI is an input-output modeling software that measures the spending patterns and location- specific economic structures to reflect expenditures supporting varying levels of employment, income, and output [17]. For his model, Croucher kept all inputs at their default selection in order to create equal ground for the study. The model for each state was the installation of 100 2.5 kW PV systems for new residential construction. His results found that out of all 50 states, Pennsylvania lead the way in terms of jobs created totaling 28.98 jobs per 100 systems. Illinois maintained second place by creating 27.65 jobs per 100 systems. A study, released in October of 2013, conducted by the Solar Foundation titled An Assessment of the Economic Revenue and Societal Impacts of Colorado’s Solar Industry, presented a snapshot of the economic and social impacts of the industry within Colorado [18]. The Foundation obtained its data from GTM Research/Solar Energy Industries Association’s U.S. Solar Market Insight from 2007-2013. This data was used for inputs into the JEDI software to find jobs created to date as well as revenues produced, earnings, andenvironmental impacts of PV installations. The Solar Foundation also conducted a scenario analysis using JEDI to predict impacts of Colorado’s Million Dollar Roof campaign. According to this study, since the year 2007, more than 10,000 jobs have been created while total earnings have accumulated $546 M. Loomis et al. [17] determined the job creation that would occur if the state installed more large-scale utility photovoltaic systems. By using results from a previous study they had conducted [19], they were able to determine what type of impact utility scale PV installations would have on the statewide economy in terms of job creation in Illinois. Different scenarios were used, thus deriving different outputs in terms of job creation. Each scenario included direct, indirect, and induced impacts, which are three distinct economic impacts. Out of this process, nine models were created with employment predictions ranging from 26,812 to 131,779 jobs statewide [17].

3. Materials

3.1. Income levels for the Town of Normal

In order to adequately conduct an economic impact study for the Town of Normal, we utilized the economic and social characteristics that define Normal. A set of data was gathered on the income levels from the year 2012 [23]. Subsequently we overlaid the income level data collected on geographic information systems (GIS), which allows the towns’ income levels to be presented on the map of the town. We then subdivided the town based upon different income levels.

3.2. Housing Characteristics for the Town of Normal

The town has a wide variation in terms of housing characteristics. Again, the Census Bureau data were used to find the Town of Normal’s housing breakdown. We have obtained information regarding housing units, the built year, the total number of rooms within the housing unit, housing tenure, average household size, year the household was occupied, and the different types of fuel used. These characteristics are beneficial when deciding which type of payment option is ideal for the different areas of the case study area. For the PV system size appropriate for each building unit, the outcomes of the first phase of this research study [20] were utilized to assess the jobs and economic impacts due to PV system implementation.

3.3. Jobs and Economic Development Impacts

For jobs and economic development impacts analysis, we utilized the Jobs and Economic Development Impacts (JEDI) Model. These models were developed by Marshall Goldberg of MRG & Associates, under contract with the National Renewable Energy Laboratory. The JEDI model utilizes multipliers obtained from IMPLAN which is maintained by the Minnesota IMPLAN Group, Inc. For the purposes of this study, the state-level multipliers built into JEDI were replaced with county-level multipliers for McLean County purchased from the Minnesota IMPLAN Group, Inc [21].

Economic multipliers are derived from industry input-output tables that detail the interrelationships between different sectors of the economy. Multipliers show how an additional dollar of spending in one sector of the economy will ripple through the economy by spurring spending in other sectors to provide that inputs into that sector. Because of differences in the economy across different geographies, economic multipliers vary depending on specific industries located in the area being studied. If an input is not sourced local, that is treated as a “leakage” from the economic impact to that specific territory.

4. Method

4.1. Evaluation of the Town of Normal Income and Housing Characteristics for Payment Options

Given that each income level is comprised of different characteristics when it comes to available funds to spend on a PV system, we created a matrix to show possible payment options at the various levels. The authors’ previous study [20] conducted a detailed analysis to identify the rooftops in the Town of Normal, Illinois that are best suited for distributed generation solar photovoltaic applications, to quantify their energy generation potential, and to evaluate the subsequent carbon mitigation potential. Percentage offsets represent the capacity of each system to reduce electrical demand depending on the average electrical consumption of the buildings in the case study area. Based upon the outcomes of this study and the literature review on a variety of financing schemes, feasible financing options were suggested to each income class. Small commercial and residential buildings that were included in the study were south facing or flat roofs only. The GIS analysis conducted in [20] revealed which buildings were applicable for each sized system as shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Percent offset and nameplate capacity [21].

| Percentage Offset | System Size | Number of Systems |

| 20% | 1.5 kW | 9,698 |

| 40% | 3 kW | 7,764 |

| 60% | 4.5 kW | 6,333 |

| 80% | 5.3 kW | 5,908 |

4.2. Using IMPLAN for Job Creation Model

The economic analysis of PV development presented here uses the NREL’s latest Jobs and Economic Development Impacts (JEDI) PV Model (PV10.17.11). The JEDI PV Model is an input-output model that measures the spending patterns and location-specific economic structures that reflect expenditures supporting varying levels of employment, income, and output for solar PV [22]. That is, the JEDI Model takes into account that the output of one industry can be used as an input for another. For example, when a PV system is installed, there are both soft costs consisting of permitting, installation and customer acquisition costs, and hardware costs, of which the PV module is the largest component. The purchase of a module not only increases demand for manufactured components and raw materials, but also supports labor [17]. When an installer and/or developer purchases a module from a manufacturing facility, the manufacturer uses some of that money to pay employees. The employees use a portion of their compensation to purchase goods and services within their community.

The total economic impact can be broken down into three distinct types including direct impacts, indirect impacts, and induced impacts [22]. Direct impacts during the construction period refer to the changes that occur in industries directly hired to install the PV system. Indirect impacts during construction period consist of the changes in inter-industry purchasesresulting from the supply chain impacts of purchases of parts that make up the PV system and associated parts [17]. Induced impacts during construction refer to the changes that occur in household spending as household income increases due to increased construction of PV systems [17].

5. Results

5.1. Payment Options for Each Income Levels

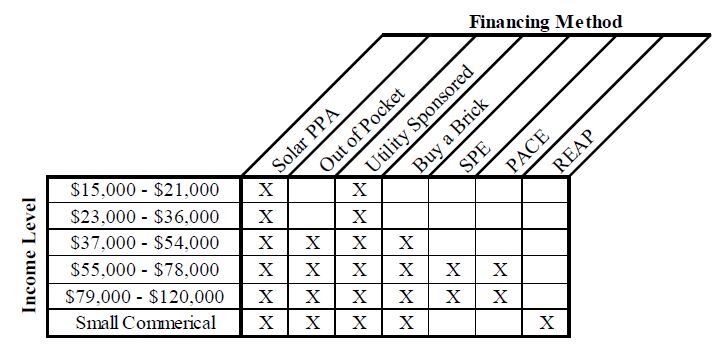

Table 3 represents which payment options are best suited for each income level. The lower the income level the fewer options are available. Income levelsranging from $15,000 to $36,000 were best suited for either a PPA or a Utility Sponsored program. Based off of the Massachusetts Institute of Technologies’ wage calculator [23], $37,000-$54,000 is the yearly income at which residents exceed their living wage. Discretionary income, or excess income, could now be allocated for items such as a PV system. Small commercial buildings were additionally provided the option of using REAP, which is available only to rural business or agricultural institutions.

Table 3. Financing Methods for Each Income Level.

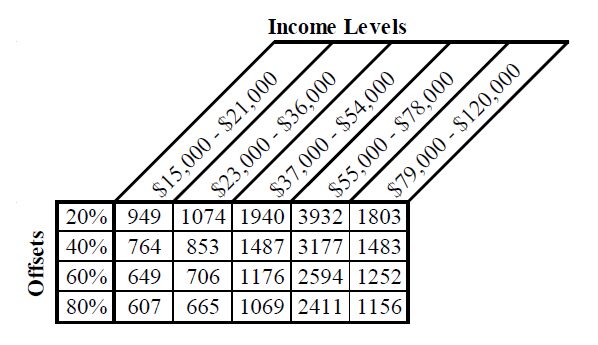

Table 4 breaks down how many systems can be installed given the income level and the percentage being offset. Higher income levels were able to support larger systems while the lower income levels, which generally had small roof areas, were only able to support of fraction of systems.

Table 4. Number of Buildings Offsetting Normal’s Average Building Energy Use.

5.2. IMPLAN

Using the JEDI model, we assess the economic impact of the four solar scenarios that were developed from the companion analysis. Depending on how technical potential is measured, we estimate the economic impact for four levels of demand—20%, 40%, 60% and 80%. A key driver of the economic impact of these different demand levels is how much of the labor and materials are sourced from within McLean County. We assume throughout the study that the solar panels are not manufactured within McLean County since there is no local manufacturer currently and we do not expect a new manufacturer to locate here. To show the possible jobs impact of growing the local solar system materials and services locally, we run two different assumptions. First, we assume the JEDI defaults. Second, we assume all of the services are sourced locally (except solar panels). Thus, we perform 8 different model runs as shown in Table 5 below:

Table 5. Eight Models Using Different Input Assumptions.

| Technical PotentialSourced | within McLean County |

| Default | 100% (excluding panels) |

| 20% | Model 1 | Model 2 |

| 40% | Model 3 | Model 4 |

| 60% | Model 5 | Model 6 |

| 80% | Model 7 | Model 8 |

In addition to the technical potential and percentage manufactured in McLean County, there are several assumptions built into the model that do not changebetween the model runs. The default settings within JEDI assume 100 residential retrofit fixed-mount crystalline-silicon systems having a nameplate capacity of 5 kW. The installed system cost is $6,562 and the annual direct operations and maintenance expense is $32.80. We do not vary the installed system cost or the operations and maintenance expense between model runs. Table 6 shows the jobs impacts for the eight different scenarios that were run for the construction phase of the projects. The jobs are reported in job-years and based on full time equivalents. This type of measurement of the jobs impacts enables us to do an apples-to-apples comparison. By this measurement, one full-time construction job lasting for one year is equivalent to 2 full-time jobs lasting six months or 4 full-time jobs lasting three months. As shown in Table 6, the total employment impacts vary from 377.4 to 1059.5 job years.

Table 6. Total McLean County Employment Impacts During Construction (Job Years).

| Percentage Manufactured in McLean County |

| Technical Potential | Default | 100% |

| 20% | 377.4 | 492.2 |

| 40% | 604.2 | 788.1 |

| 60% | 739.3 | 964.3 |

| 80% | 812.2 | 1,059.50 |

Table 7 shows the ongoing operations and maintenance jobs that will result under each scenario. The operations and maintenance jobs are not dependent on where the original equipment was manufactured, so the jobs impact only varies by the assumed installed capacity. Although some replacement parts will be required from time to time, the supply chain impacts from this small amount of equipment is overshadowed by the direct labor involved in operations and maintenance. The employment impacts during the operating years vary from 18.8 to 40.5. Because there are few existing solar installations in McLean County and the industry is not well developed, all of the labor would be sourced from outside the County under the Default scenarios using existing economic multipliers.

Table 7. Total McLean County Employment Impacts During Operating Years (Job Years).

| Technical Potential | Default | 100% |

| 20% | 0 | 18.8 |

| 40% | 0 | 30.1 |

| 60% | 0 | 36.8 |

| 80% | 0 | 40.5 |

When measuring the economic impact, one is concerned with the earnings of these workers as well as the total number of jobs created. Table 8 shows the total McLean County earnings impacts for the eight different scenarios that were run for the construction phase. The earnings are reported in thousands of 2012 dollars so that they are adjusted for the fact that jobs created in future years may have higher earnings due to inflation alone. As shown in Table 8, the total earnings impacts vary from $30.3 million to $65.2 million.

Table 8. Total McLean County Earnings Impacts During Construction ($ Thousands 2012).

| Technical Potential | Default | 100% |

| 20% | $23,282.60 | $30,300.80 |

| 40% | $37,279.10 | $48,516.20 |

| 60% | $45,612.10 | $59,361.10 |

| 80% | $50,115.80 | $65,222.40 |

The final and largest measure of economic impact is total output impacts. Table 9 shows the total McLean County output impacts for the eight different scenarios that were run for the construction phase. Output is reported in thousands of 2012 dollars so that they are adjusted for the fact that output in future years may be higher due to inflation alone. As shown in Table 9, the total earnings impacts vary from $68.5 million to $165.6 million.

Table 9. Total McLean County Output Impacts During Construction ($ Thousands 2012).

| Technical Potential | Percentage Manufactured in McLean County |

| Default | 100% |

| 20% | $68,531.40 | $76,932.90 |

| 40% | $109,729.30 | $123,181.60 |

| 60% | $134,257.30 | $150,716.50 |

| 80% | $147,513.70 | $165,598.10 |

6. Discussion and Conclusion

This study has created a simplified model for both the purchasing process as well as the selling and designing process that is attached to the acquisition of soft and hard goods related to solar products. As each percentage option has a fixed nameplate capacity, as well as a fixed price, the burden on the PV providers of designing specific systems for each building is eliminated. Any potential customer could specify which percent system they wished to have installed, and the solar installer would know the exact specifications required.

A possible funding solution for distributed systems would be to institute a feed-in tariff (FIT). Feed-in tariffs require energy suppliers to buy electricity produced from renewable resources at a fixed price per kilowatt-hour, usually for a fixed period [8]. FITs are seen globally and are accepted as the main driver for renewable technology implementation. State and local governments can implement such a tariff by incorporating it into their renewable portfolio standard (RPS). Along with their RPS, FITs can advance the development process of renewable technologies throughout the country. Future research could look at all possible payment methods used in the country and throughout the world.

This study used available funding options for PV in the state of Illinois to provide payment options to residents in the Town of Normal, IL. Given information collected from literature reviews and case studies, the payment options were suggested viable methods for residential and small commercial buildings given their income levels. An economic impact study was conducted in order to quantify job creation due to PV installations at eachpercent level. The estimated stimulus respective to each level of implementation can potentially impact a broad spectrum of income levels. This research study’s objective of deployment optimization required a thorough analysis and proper consideration, given the prospect of positive implications on those who participate in Normal, Illinois.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest regarding this paper.

DownLoad:

DownLoad: