|

[1]

|

Carninci P, Kasukawa T, Katayama S, et al. (2005) The transcriptional landscape of the mammalian genome. Science 309: 1559–1563. doi: 10.1126/science.1112014

|

|

[2]

|

Harrow J, Frankish A, Gonzalez JM, et al. (2012). GENCODE: the reference human genome annotation for The ENCODE Project. Genome Res 22: 1760–1774.

|

|

[3]

|

Esteller M (2011) Non-coding RNAs in human disease. Nature Rev Gene 12: 861–874.

|

|

[4]

|

Beermann J, Piccoli MT, Viereck J, et al. (2016) Non-coding RNAs in development and disease: background, mechanisms, and therapeutic approaches. Physiol Rev 96: 1297–1325. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00041.2015

|

|

[5]

|

Barwari T, Joshi A, Mayr M (2016) MicroRNAs in Cardiovascular Disease. J Am College Cardiol 68: 2577–2584. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.09.945

|

|

[6]

|

Liu N, Olson EN (2010) MicroRNA regulatory networks in cardiovascular development. Dev Cell 18: 510–525. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.03.010

|

|

[7]

|

Derrien T, Johnson R, Bussotti G, et al. (2012) The GENCODE v7 catalog of human long noncoding RNAs: analysis of their gene structure, evolution, and expression. Genome Res 22: 1775–1789. doi: 10.1101/gr.132159.111

|

|

[8]

|

Fang S, Zhang L, Guo J, et al. (2017) NONCODEv5: a comprehensive annotation database for long non coding RNAs. Nucleic Acids Res 46: D308–D314.

|

|

[9]

|

Schmitz SU, Grote P, Herrmann BG (2016) Mechanisms of long noncoding RNA function in development and disease. Cell Mol Life Sci 73: 2491–2509. doi: 10.1007/s00018-016-2174-5

|

|

[10]

|

Rosa A, Ballarino M (2015) Long noncoding RNA regulation of pluripotency. Stem Cells Int 2016: 1–9.

|

|

[11]

|

Wapinski O, Chang HY (2011) Long noncoding RNAs and human disease. Trends in Cell Biol 21: 354–361. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2011.04.001

|

|

[12]

|

Dieci G, Fiorino G, Castelnuovo M, et al. (2007) The expanding RNA polymerase III transcriptome. Trends in Genet 23: 614–622. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2007.09.001

|

|

[13]

|

Rackham O, Shearwood AMJ, Mercer TR, et al. (2011) Long noncoding RNAs are generated from the mitochondrial genome and regulated by nuclear-encoded proteins. RNA 17: 2085–2093. doi: 10.1261/rna.029405.111

|

|

[14]

|

Pauli A, Norris ML, Valen E, et al. (2014) Toddler: an embryonic signal that promotes cell movement via Apelin receptors. Science 343: 1248636. doi: 10.1126/science.1248636

|

|

[15]

|

Pauli A, Valen E, Schier AF (2015) Identifying (non‐) coding RNAs and small peptides: Challenges and opportunities. BioEssays 37: 103–112. doi: 10.1002/bies.201400103

|

|

[16]

|

Nelson BR, Makarewich CA, Anderson DM, et al. (2016) A peptide encoded by a transcript annotated as long noncoding RNA enhances SERCA activity in muscle. Science 351: 271–275. doi: 10.1126/science.aad4076

|

|

[17]

|

Engreitz JM, Ollikainen N, Guttman M (2016) Long non-coding RNAs: spatial amplifiers that control nuclear structure and gene expression. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 17: 756–770. doi: 10.1038/nrm.2016.126

|

|

[18]

|

Gloss BS, Dinger ME (2016) The specificity of long noncoding RNA expression. Biochim Biophysi Acta 1859: 16–22. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2015.08.005

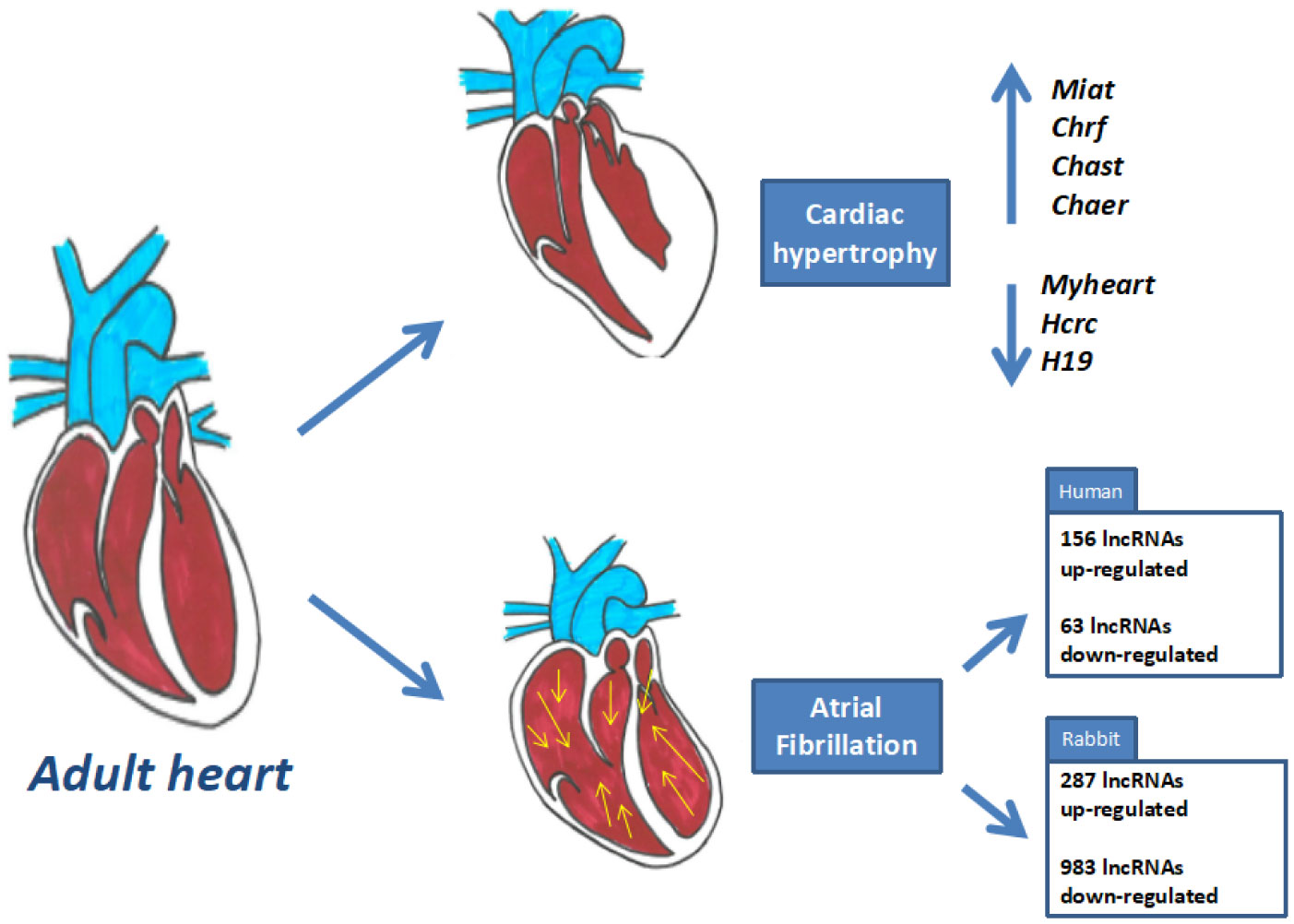

|

|

[19]

|

Bär C, Chatterjee S, Thum T (2016) Long Noncoding RNAs in Cardiovascular Pathology, Diagnosis, and Therapy. Circulation 134: 1484–1499. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.023686

|

|

[20]

|

Chen LL (2016) Linking Long Noncoding RNA Localization and Function. Trends in Biochem Sci 41: 761–772. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2016.07.003

|

|

[21]

|

Klattenhoff CA, Scheuermann JC, Surface LE, et al. (2013) Braveheart, a long noncoding RNA required for cardiovascular lineage commitment. Cell 152: 570–583. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.01.003

|

|

[22]

|

Ulitsky I, Bartel DP (2013) lincRNAs: genomics, evolution, and mechanisms. Cell 154: 26–46. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.06.020

|

|

[23]

|

Ounzain S, Pedrazzini T (2015) The promise of enhancer-associated long noncoding RNAs in cardiac regeneration. Trends Cardiovasc Med 25: 592–602. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2015.01.014

|

|

[24]

|

Ounzain S, Burdet F, Ibberson M, et al. (2015) Discovery and functional characterization of cardiovascular long noncoding RNAs. J Mol Cell Cardiol 89: 17–26. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2015.09.013

|

|

[25]

|

Memczak S, Jens M, Elefsinioti A, et al. (2013) Circular RNAs are a large class of animal RNAs with regulatory potency. Nature 495: 333–338. doi: 10.1038/nature11928

|

|

[26]

|

Wang K, Long B, Liu F, et al. (2016) A circular RNA protects the heart from pathological hypertrophy and heart failure by targeting miR-223. Euro Heart J 37: 2602–2611. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv713

|

|

[27]

|

Liu L, An X, Li Z, et al. (2016) The H19 long noncoding RNA is a novel negative regulator of cardiomyocyte hypertrophy. Cardiovasc Res 111: 56–65. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvw078

|

|

[28]

|

Hasegawa Y, Brockdorff N, Kawano S, et al. (2010) The matrix protein hnRNP U is required for chromosomal localization of Xist RNA. Dev Cell 19: 469–476. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.08.006

|

|

[29]

|

Gupta RA, Shah N, Wang KC, et al. (2010) Long non-coding RNA HOTAIR reprograms chromatin state to promote cancer metastasis. Nature 464: 1071–1076. doi: 10.1038/nature08975

|

|

[30]

|

Grote P, Wittler L, Hendrix D, et al. (2013) The tissue-specific lncRNA Fendrr is an essential regulator of heart and body wall development in the mouse. Dev Cell 24: 206–214. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2012.12.012

|

|

[31]

|

Tsai M C, Manor O, Wan Y, et al. (2010) Long noncoding RNA as modular scaffold of histone modification complexes. Science 329: 689–693. doi: 10.1126/science.1192002

|

|

[32]

|

Aguilo F, Zhou MM, Walsh MJ (2011) Long noncoding RNA, polycomb, and the ghosts haunting INK4b-ARF-INK4a expression. Cancer Res 71: 5365–5369. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-4379

|

|

[33]

|

Mousavi K, Zare H, Dell'Orso S, et al. (2013) eRNAs promote transcription by establishing chromatin accessibility at defined genomic loci. Mol Cell 51: 606–617. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.07.022

|

|

[34]

|

Welsh IC, Kwak H, Chen FL, et al. (2015) Chromatin architecture of the Pitx2 locus requires CTCF-and Pitx2-dependent asymmetry that mirrors embryonic gut laterality. Cell Rep 13: 337–349. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.08.075

|

|

[35]

|

Redon S, Reichenbach P, Lingner J (2010) The non-coding RNA TERRA is a natural ligand and direct inhibitor of human telomerase. Nucleic Acids Res 38: 5797–5806. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq296

|

|

[36]

|

Han P, Li W, Lin CH, et al. (2014) A long noncoding RNA protects the heart from pathological hypertrophy. Nature 514: 102–106. doi: 10.1038/nature13596

|

|

[37]

|

Yoon JH, Abdelmohsen K, Gorospe M (2013) Posttranscriptional gene regulation by long noncoding RNA. J Mol Biol 425: 3723–3730. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2012.11.024

|

|

[38]

|

Tripathi V, Ellis JD, Shen Z, et al. (2010) The nuclear-retained noncoding RNA MALAT1 regulates alternative splicing by modulating SR splicing factor phosphorylation. Mol Cell 39: 925–938. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.08.011

|

|

[39]

|

Yin QF, Yang L, Zhang Y, et al. (2012) Long Noncoding RNAs with snoRNA Ends. Mol Cell 48: 219–230. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.07.033

|

|

[40]

|

Kim YK, Furic L, Desgroseillers L, et al. (2005) Mammalian Staufen1 recruits Upf1 to specific mRNA 3'UTRs so as to elicit mRNA decay. Cell 120: 195–208 doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.11.050

|

|

[41]

|

Kim YK, Furic L, Parisien M, et al. (2007) Staufen1 regulates diverse classes of mammalian transcripts. EMBO 26: 2670–2681 doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601712

|

|

[42]

|

Faghihi MA, Modarresi F, Khalil AM, et al. (2008) Expression of a noncoding RNA is elevated in Alzheimer's disease and drives rapid feed-forward regulation of β-secretase expression. Nat Med 14: 723. doi: 10.1038/nm1784

|

|

[43]

|

Faghihi MA, Zhang M, Huang J, et al. (2010) Evidence for natural antisense transcript-mediated inhibition of microRNA function. Genome Biol 11: R56.

|

|

[44]

|

Yoon JH, Abdelmohsen K, Srikantan S, et al. (2012) LincRNA-p21 suppresses target mRNA translation. Mol Cell 47: 648–655. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.06.027

|

|

[45]

|

Wang H, Iacoangeli A, Lin D, et al. (2005) Dendritic BC1 RNA in translational control mechanisms. J Cell Biol 171: 811–821. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200506006

|

|

[46]

|

Carrieri C, Cimatti L, Biagioli M, et al. (2012) Long non-coding antisense RNA controls Uchl1 translation through an embedded SINEB2 repeat. Nature 491: 454–457. doi: 10.1038/nature11508

|

|

[47]

|

Cesana M, Cacchiarelli D, Legnini I, et al. (2011) A long noncoding RNA controls muscle differentiation by functioning as a competing endogenous RNA. Cell 147: 358–369. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.09.028

|

|

[48]

|

Keniry A, Oxley D, Monnier P, et al. (2012) The H19 lincRNA is a developmental reservoir of miR-675 which suppresses growth and Igf1r. Nat Cell Biol 14: 659. doi: 10.1038/ncb2521

|

|

[49]

|

Garry DJ, Olson EN (2006) A common progenitor at the heart of development. Cell 127: 1101–1104. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.11.031

|

|

[50]

|

Wagner M, Siddiqui MAQ (2007) Signal transduction in early heart development (I): cardiogenic induction and heart tube formation. Exp Biol Med 232: 852–865.

|

|

[51]

|

Kelly RG, Buckingham ME, Moorman AF (2014) Heart fields and cardiac morphogenesis. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 4: a015750.

|

|

[52]

|

Christoffels VM, Habets PE, Franco D, et al. (2000) Chamber formation and morphogenesis in the developing mammalian heart. Dev Biol 223: 266–278. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.9753

|

|

[53]

|

Schonrock N, Harvey RP, Mattick JS (2012) Long noncoding RNAs in cardiac development and pathophysiology. Circ Res 111: 1349–1362. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.268953

|

|

[54]

|

Meganathan K, Sotiriadou I, Natarajan K, et al. (2015) Signaling molecules, transcription growth factors and other regulators revealed from in-vivo and in-vitro models for the regulation of cardiac development. Int J Cardiol 183: 117–128. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2015.01.049

|

|

[55]

|

Stefani G, Slack FJ (2008) Small non-coding RNAs in animal development. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 9: 219–230. doi: 10.1038/nrm2347

|

|

[56]

|

Katz MG, Fargnoli AS, Kendle AP, et al. (2016) The role of microRNAs in cardiac development and regenerative capacity. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 310: H528–H541. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00181.2015

|

|

[57]

|

Li H, Jiang L, Yu Z, et al. (2017) The Role of a Novel Long Noncoding RNA TUC40-in Cardiomyocyte Induction and Maturation in P19 Cells. Am J Med Sci 354: 608–616. doi: 10.1016/j.amjms.2017.08.019

|

|

[58]

|

Arnone B, Chen JY, Qin G (2017) Characterization and analysis of long non-coding rna (lncRNA) in In Vitro-and Ex Vivo-derived cardiac progenitor cells. PloS One 12: e0180096. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0180096

|

|

[59]

|

Liu J, Li Y, Lin B, et al. (2017) HBL1 Is a Human Long Noncoding RNA that Modulates Cardiomyocyte Development from Pluripotent Stem Cells by Counteracting MIR1. Dev Cell 42: 333–348. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2017.07.023

|

|

[60]

|

Ounzain S, Micheletti R, Beckmann T, et al. (2014) Genome-wide profiling of the cardiac transcriptome after myocardial infarction identifies novel heart-specific long non-coding RNAs. Eur Heart J 36: 353–368.

|

|

[61]

|

Ounzain S, Pedrazzini T (2016) Long non-coding RNAs in heart failure: a promising future with much to learn. Annals Trans Med 4: 298. doi: 10.21037/atm.2016.07.13

|

|

[62]

|

Ounzain S, Micheletti R, Arnan C, et al. (2015) CARMEN, a human super enhancer-associated long noncoding RNA controlling cardiac specification, differentiation and homeostasis. J Mol Cell Cardiol 89: 98–112. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2015.09.016

|

|

[63]

|

Boucher JM, Peterson SM, Urs S, et al. (2011) The miR-143/145 cluster is a novel transcriptional target of Jagged-1/Notch signaling in vascular smooth muscle cells. J Biol Chem 286: 28312–28321. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.221945

|

|

[64]

|

Cordes KR, Sheehy NT, White MP, et al. (2009) miR-145 and miR-143 regulate smooth muscle cell fate and plasticity. Nature 460: 705–710.

|

|

[65]

|

Mathiyalagan P, Keating ST, Du XJ, et al. (2014) Chromatin modifications remodel cardiac gene expression. Cardiovasc Res 103: 7–16.

|

|

[66]

|

Xue Z, Hennelly S, Doyle B, et al. (2016) A G-rich motif in the lncRNA braveheart interacts with a zinc-finger transcription factor to specify the cardiovascular lineage. Mol Cell 64: 37–50. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.08.010

|

|

[67]

|

Mahlapuu M, Ormestad M, Enerback S, et al. (2001) The forkhead transcription factor Foxf1 is required for differentiation of extra-embryonic and lateral plate mesoderm. Development 128: 155–166.

|

|

[68]

|

Grote P, Herrmann BG (2013) The long non-coding RNA Fendrr links epigenetic control mechanisms to gene regulatory networks in mammalian embryogenesis. RNA Biol 10: 1579–1585. doi: 10.4161/rna.26165

|

|

[69]

|

79. Kurian L, Aguirre A, Sancho-Martinez I, et al. (2015) Identification of novel long non-coding RNAs underlying vertebrate cardiovascular development. Circulation 131: 1278–1290. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.013303

|

|

[70]

|

Jiang W, Liu Y, Liu R, et al. (2015) The lncRNA DEANR1 facilitates human endoderm differentiation by activating FOXA2 expression. Cell Rep 11: 137–148. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.03.008

|

|

[71]

|

Yamagashi H, Olson EN, Srivastava D (2000) The basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor, dHAND, is required for vascular development. J Clin Invest 105: 261–270. doi: 10.1172/JCI8856

|

|

[72]

|

McFadden DG, Charité J, Richardson JA, et al. (2000) A GATA-dependent right ventricular enhancer controls dHAND transcription in the developing heart. Development 127: 5331–5341.

|

|

[73]

|

He A, Gu F, Hu Y, et al. (2014) Dynamic GATA4 enhancers shape the chromatin landscape central to heart development and disease. Nat Commun 5: 4907. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5907

|

|

[74]

|

Anderson KM, Anderson DM, McAnally JR, et al. (2016) Transcription of the non-coding RNA upperhand controls Hand2 expression and heart development. Nature 539: 433–436. doi: 10.1038/nature20128

|

|

[75]

|

Song G, Shen Y, Zhu J, et al. (2013) Integrated analysis of dysregulated lncRNA expression in fetal cardiac tissues with ventricular septal defect. PloS One 8: e77492. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0077492

|

|

[76]

|

Song G, Shen Y, Ruan Z, et al. (2016) LncRNA-uc. 167 influences cell proliferation, apoptosis and differentiation of P19 cells by regulating Mef2c. Gene 590: 97–108.

|

|

[77]

|

Gudbjartsson DF, Arnar DO, Helgadottir A, et al. (2007) Variants conferring risk of atrial fibrillation on chromosome 4q25. Nature 448: 353–357. doi: 10.1038/nature06007

|

|

[78]

|

Ellinor PT, Lunetta KL, Albert CM, et al. (2012) Meta-analysis identifies six new susceptibility loci for atrial fibrillation. Nat Genet 44: 670–675. doi: 10.1038/ng.2261

|

|

[79]

|

Franco D, Christoffels VM, Campione M (2014) Homeobox transcription factor Pitx2: The rise of an asymmetry gene in cardiogenesis and arrhythmogenesis. Trends Cardiovasc Med 24: 23–31. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2013.06.001

|

|

[80]

|

Gore-Panter SR, Hsu J, Barnard J, et al. (2016) PANCR, the PITX2 Adjacent noncoding RNA, is expressed in human left atria and regulates PITX2c expression. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 9: e003197. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.115.003197

|

|

[81]

|

Guo Y, Luo F, Liu Q, et al. (2016) Regulatory non‐coding RNAs in acute myocardial infarction. J Cell Mol Med 21: 1013–1023.

|

|

[82]

|

Vausort M, Wagner DR, Devaux Y (2014) Long Noncoding RNAs in Patients With Acute Myocardial InfarctionNovelty and Significance. Circ Res 115: 668–677. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.303836

|

|

[83]

|

Devaux Y, Creemers EE, Boon RA, et al. (2017) Circular RNAs in heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail 19: 701–709. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.801

|

|

[84]

|

Greco S, Zaccagnini G, Perfetti A, et al. (2016) Long noncoding RNA dysregulation in ischemic heart failure. J Transl Med 14: 183. doi: 10.1186/s12967-016-0926-5

|

|

[85]

|

Schiano C, Costa V, Aprile M, et al. (2017) Heart failure: Pilot transcriptomic analysis of cardiac tissue by RNA-sequencing. Cardiol J 24: 539–553. doi: 10.5603/CJ.a2017.0052

|

|

[86]

|

Micheletti R, Plaisance I, Abraham BJ, et al. (2017) The long noncoding RNA Wisper controls cardiac fibrosis and remodeling. Sci Transl Med 9: eaai9118. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aai9118

|

|

[87]

|

Li Z, Wang X, Wang W, et al. (2017) Altered long non-coding RNA expression profile in rabbit atria with atrial fibrillation: TCONS_00075467 modulates atrial electrical remodeling by sponging miR-328 to regulate CACNA1C. J Mol Cell Cardiol 108: 73–85. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2017.05.009

|

|

[88]

|

Ruan Z, Sun X, Sheng H, et al. (2015) Long non-coding RNA expression profile in atrial fibrillation. Int J Clin Exp Pathol 8: 8402.

|

|

[89]

|

Viereck J, Kumarswamy R, Foinquinos A, et al. (2016) Long noncoding RNA Chast promotes cardiac remodeling. Sci Transl Med 8: 326ra22–326ra22.

|

|

[90]

|

Wang Z, Zhang XJ, Ji YX, et al. (2016) The long noncoding RNA Chaer defines an epigenetic checkpoint in cardiac hypertrophy. Nat Med 22: 1131–1139. doi: 10.1038/nm.4179

|

|

[91]

|

Wang K, Liu F, Zhou LY, et al. (2014) The Long Noncoding RNA CHRF Regulates Cardiac Hypertrophy by Targeting miR-489 Novelty and Significance. Circ Res 114: 1377–1388. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.114.302476

|

|

[92]

|

Zhu XH, Yuan YX, Rao SL, et al. (2016) Lncrna miat enhances cardiac hypertrophy partly through sponging mir-150. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 20: 3653.

|

|

[93]

|

Piccoli MT, Gupta SK, Viereck J, et al. (2017) Inhibition of the Cardiac Fibroblast–Enriched lncRNA Meg3 Prevents Cardiac Fibrosis and Diastolic Dysfunction Novelty and Significance. Circ Res 121: 575–583. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.117.310624

|

|

[94]

|

Tao H, Zhang JG, Qin RH, et al. (2017) LncRNA GAS5 controls cardiac fibroblast activation and fibrosis by targeting miR-21 via PTEN/MMP-2 signaling pathway. Toxicology 386: 11–18. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2017.05.007

|

|

[95]

|

Qu X, Du Y, Shu Y, et al. (2017) MIAT is a pro-fibrotic long non-coding RNA governing cardiac fibrosis in post-infarct myocardium. Sci Rep 7: 42657. doi: 10.1038/srep42657

|

|

[96]

|

Huang ZW, Tian LH, YangB, et al. (2017) Long noncoding RNA H19 acts as a competing endogenous RNA to mediate CTGF expression by sponging miR-455 in cardiac fibrosis. DNA Cell Biol 36: 759–766.

|

DownLoad:

DownLoad: