1.

Introduction

Dyes are colored substances and they are solubilized during the application and impart color by selective absorption of light [1]. Dye molecules consist of a chromophore component (largely responsible for producing the color) and auxochrome component (as a supplement to the chromophore but also render the molecule soluble in water and improves its attachment toward the fibers) [2]. Yagub et al. [3] mentioned that dyes can be classified based on their particle charge upon dissolution in aqueous application. The dyes can be grouped into cationic (basic dyes), anionic (direct, acid and reactive) and non-ionic (dispersed).

Textile, cosmetic and paper industry use dyes as coloring agents. Five industries are known to be responsible for the presence of dye effluents in the environment: textile (54%), dyeing (21%), paper and pulp (10%), tannery and paint (8%) and dye manufacturers (7%) [4]. Therefore, the textile industry generates more than half of dye effluents, with a worldwide dye discharge estimated of 280,000 ton/year as mentioned by Jin et al. [5].

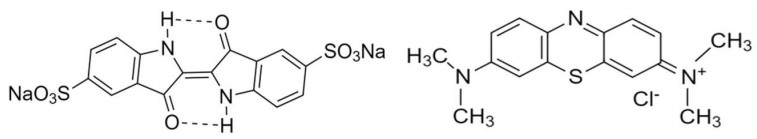

Indigo carmine (IC) and methylene blue (MB) are common dyes used as dyeing agents in the textile industry. They are anionic and cationic dyes, respectively [6,7,8,9]. Figure 1 shows the chemical structure of indigo carmine and methylene blue dyes.

The processes for color removal can be classified into physical, chemical and biological [2,4,12]; however, Hao et al. [12] have also mentioned the electrical process. Biological and physical methods are considered as the most efficient dye removal processes [2,4]. Murugan et al. [9] mentioned that most of methods adopted for removal of compounds (organic and inorganic) from the wastewater are expensive and not suitable for small scale industries. Moreover, photocatalysis (chemical treatment) is a high effective and low-cost process compared to other methods [9,13]. This method was applied by Frank and Bard [14] to degrade pollutants in aqueous solution and allowed the theorical foundation for photocatalytic oxidation technology in wastewater treatment. Furthermore, some authors have reported photocatalytic studies in this field [15,16,17,18]. It has been reported that the photocatalytic process involves three steps. Firstly, absorption of photons with energy larger than the band gap of a photocatalyst. Secondly, the generation, separation, migration or recombination of electron-hole pairs photo generated and finally, the redox reactions at the photocatalyst surface [9].

The photocatalytic activity of some semiconductors as titanium dioxide [15,16,19], zinc oxide [19,20,21], zirconium oxide [22], tin oxide [23], cadmium sulfide [24] and bismuth compounds [25,26], has been studied under light irradiation. CeO2 (ceria) is an n-type semiconductor with a wide bandgap [13] and remarkable features such as chemical stability, low-cost and low-toxicity [27,28]. It can be used in a wide range of different applications such as Solid Oxide Fuel Cells (SOFC) [13,29], oxidation of Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs) [13,30], aerobic oxidation of alcohols [31], photodegradation of toluene gas [32,33], biomedical applications [13,34] and photocatalyst in wastewater treatment [13,32,35].

Cerium oxide has been used by several authors to degrade dyes. Sane et al. [27] reported > 95% removal of reactive dyes (reactive green-19, reactive orange-84 and reactive yellow-81) under visible light within 240 min by using CeO2 synthesized by precipitation. Zheng et al. [35] reported the adsorption capacity of CeO2 nanoparticles for Congo red (CR) is closely related to its morphology. In their work, the adsorption performance was attributed to the structure and presence of electrostatic interactions between the nanoparticles surface and dye molecules.

In addition, cerium oxide has been also used by diverse authors to degrade methylene blue. However, there is still a controversy in the literature about the effect of those particles in the dye degradation. Miyauchi et al. [36] and Kumar et al. [17] have mentioned that CeO2 thin films are inactive for photocatalytic degradation of methylene blue. Tuyen et al. [37] reported that CeO2 could not catalyze the photodegradation of MB. Majumder et al. [38] studied CeO2 nanoparticles with different morphologies as catalyst for degradation of MB at pH 3. They found that hexagonal and rectangular shapes had not a good catalytic performance even after 200 min of UV irradiation. However, CeO2 nanoparticles with square shape showed excellent photocatalytic performance with complete degradation of MB (4.6 μM) within 175 min.

However, other authors have reported the effectiveness of CeO2 NPs in the degradation of MB dye. Pouretedal and Kadkhodaie [39] studied the degradation efficiency of MB (20 mg/L) catalyzed by CeO2 nanoparticles (1.0 g/L) at different pH values, and reported 85% of dye degradation at pH 11 within 175 min. Zhang et al. [40] studied fly ash cenospheres (FACs)-supported CeO2 composite (CeO2/FACs) and obtained a promising catalyst for photocatalytic decolorization of MB. A color removal up to 60% after irradiation for 300 min was achieved. In a recent work, Murugan et al. [9] have mentioned than an enhanced photodegradation of MB can be found by using CeO2 nanoparticles doped with alkaline metal ion (Mg, Ca, Sr, Ba) compared to pure CeO2 nanoparticles. Yang et al. [28] mentioned that, calcination temperature for synthesis of CeO2 nanofibers catalyst has a positive effect for the photocatalytic performance. They reported that the photodegradation rate of MB increases from 67% to 98% for CeO2 nanofibers obtained at 500 and 800 ℃, respectively.

Moreover, based on reported literature, cerium oxide has been used to degrade several dyes, but limited work has been done and focused on the degradation of indigo carmine solutions by using of CeO2. Indigo carmine is one of the oldest and most important dyes used as dyeing agent of clothes (blue jeans) and other blue denim products [41,42,43,44,45,46,47]. To the best of the authors knowledge the work of Liyanage et al. [48] is the only article available in the literature related to degradation of indigo carmine by using cerium oxide. They found that yttrium-doped ceria nanorods displayed a better photocatalytic activity for the degradation of indigo carmine dye solution at room temperature under UV irradiation, compared to the pure ceria.

Summarizing, only a few of authors have studied the removal of color from indigo carmine solutions using cerium oxide and the materials used in that paper are not nanoparticles but nanorods. In addition, as shown in Table 1, several references were carefully reviewed and there is no consensus in the literature to conclude that cerium oxide particles are useful to degrade dye solutions. Accordingly, the aim of this article is to determine the ability of ceria nanoparticles synthesized via sol-gel method to remove and/or degrade methylene blue and indigo carmine, by modifying the pH of the dye solution. Moreover, the data reported in this article provides useful information related to the use of cerium oxide to degrade methylene blue since there is not agreement in the literature.

2.

Experimental section

2.1. Synthesis of CeO2 NPs

Cerium oxide nanoparticles were prepared via sol-gel method, following the procedure mentioned by He et al. [49] with some modifications. The chemical reagents used were cerium (III) nitrate hexahydrate (Ce(NO3)3·6H2O, ≥ 98.5%, Chemí) as cerium oxide precursor, urea (CO(NH2)2, ≥ 99.5%, Carlo Erba) and polyvinylpyrrolidone ((C6H9NO)n, ≥ 95.00%, M.W. 58,000, Alfa Aesar) as surfactant. The desired concentration of the reagents was dissolved into deionized water (conductivity lower than 0.4 μS) in a beaker to produce a clear solution. The solution was stirred at 300 rpm (magnetic stirrer) during 15 min and subsequently, the temperature of the solution was increased from room temperature to 90 ℃ and it was kept for up to 3 h. The pH was controlled between 8.2–8.5 (by adding dropwise ammonia with a burette) for about 4 h. A color variation phenomenon was observed, and it was correlated with chemical changes as mentioned by He et al. [49]. All mentioned chemical reagents were analytical grade and they were used without any further purification.

The solvents were eliminated from the solution by rotary evaporation at 85 rpm and 85 ℃ during 4 h. Nanoparticles (3 g) were added in 40 mL of deionized water (DI) or ethanol (EtOH). Later, the nanoparticles were separated by sonication and centrifugation at 10,000 rpm during 30 min/cycle to remove traces of ammonia and cerium nitrate. The resulting precipitates were drained and dried in an oven (Binder KB 115) at 80 ℃ overnight. The resulting particles were calcined at 500 ℃ in a tube furnace (Nabertherm P330) for 2 h.

2.2. Characterization of CeO2 NPs

The structural properties of CeO2 NPs were determined by X-ray diffraction (XRD) with a PANalytical X’Pert PRO diffractometer. The samples were scanned in the range of 2θ = 20–80° at a scanning speed of 0.02 °/s, using Cu Kα radiation at 45 kV and 40 mA. The crystallite size was calculated by using Scherrer’s formula [50] and the most intense peak of the diffractogram (111) was used for this calculation. The surface chemistry of CeO2 NPs was analyzed by using an X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS, SPECS) with a PHOIBOS 150 1D-DLD analyzer and monochromatic Al Kα radiation (13 kV, 1487 eV and 100 W). The calibration and correction of binding energy were accomplished by assuming the binding energy of the adventitious carbon (C 1s) to 284.6 eV. The relative concentration of the cations Ce3+ and Ce4+ were calculated as [51]:

Where Ai is the integrated area of peak “i”, u and v indicate the spin-orbit coupling states of 3d3/2 and 3d5/2, respectively. v0, v’,

u0 and u’ are characteristic peaks of Ce3+; while v, v’’, v’’’, u, u’’, and u’’’ are characteristic of Ce4+.

The morphology of the nanoparticles was studied by using Field-Emission Scanning Electron Microscopy (FEG-SEM) (JEOL JSM-7100 F). The particles were measured using several SEM images and the size distribution of the nanoparticles was determined by using ImageJ free software. In addition, an elemental analysis of nanoparticles was performed using Energy-Dispersive Spectrometry (EDS) coupled to the SEM.

The presence of functional groups in ceria nanoparticles was investigated by using Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) in a Shimadzu IR Tracer-100 spectrometer with wave number range 4000–400 cm−1 and resolution 4 cm−1. The samples were prepared by using conventional KBr. Zeta potential of nanoparticles was measured by using a Zetasizer Nanoplus 3HD instrument and the absorption spectra was determined on a UV-vis Agilent 8453 spectrophotometer, in the range of wavelengths between 200–900 nm. For both tests (Z potential and UV) a suspension with a concentration around of 1000 ppm was previously prepared and sonicated for 15 min.

2.3. Photocatalytic activity of CeO2 NPs

Photocatalytic activity of CeO2 nanoparticles was studied for Indigo Carmine (IC) and Methylene Blue (MB) dye solutions (30 ppm in all cases). During color removal tests, 60 mg of ceria nanoparticles were added to 100 mL of dye solution. In this study, the concentration of NPs was fixed at 600 ppm since it is a medium value reported in the literature by other authors [16,35]. The pH of the dye solution is an important parameter during the adsorption process because it can alter the surface charge of the adsorbent and the dyes ionization degree [35]. Accordingly, the effect of the dye solution pH (2.5, 8.0 and 10.0) on the IC and MB degradation by CeO2 NPs was studied. The pH values were adjusted using 0.1 M NaOH and 0.1 M HCl. Moreover, the degradation of IC dye was carried out in absence of ceria nanoparticles under UV irradiation (photolysis) at the unmodified pH of the solution (pH = 5.6).

During the degradation tests, the solution was controlled, kept at room temperature (298 ± 1 K) and magnetically stirred (300 rpm). Prior to irradiation, the nanoparticles were added to the dye solution to reach an adsorption-desorption equilibrium (60 min under dark and previous UV irradiation). A lamp with 15 W (Lumek) was used as a UV-C source to trigger the photocatalytic reaction. This UV source covers the wavelength range of 100–280 nm, in accordance to suitable radiation < 420 nm to transfer electrons from the valance band to the conduction band mentioned by Pouretedal and Kadkhodaie [39].

The distance between the UV source and the beaker containing the solution was controlled to 10 cm [9,17]. Aliquots were taken at pre-set time intervals during irradiation and ceria nanoparticles were separated by centrifugation at 10,000 rpm for 15 min. The concentration of remaining IC and MB in the supernatant was monitored by measuring the absorbance at λmax 610 and 663 nm, respectively, by UV-vis spectroscopy (Agilent 8453 spectrophotometer). The color removal of dye solution was calculated by the equation reported by Ameen et al. [52], as follows:

Where C0 and C refers to initial and variable concentrations of dye solution, respectively. A0 represents the initial absorbance and A at pre-set time.

3.

Results and discussion

3.1. Chemical and physical characterization of CeO2 NPs

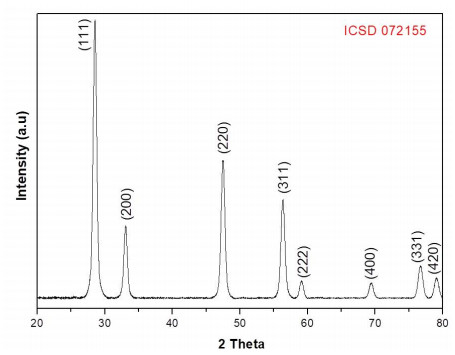

The XRD patterns of synthesized CeO2 nanoparticles can be observed in Figure 2. The CeO2 nanoparticles exhibited diffraction peaks at 28.54°, 33.07°, 47.55°, 56.22°, 59.05°, 69.26°, 76.75° and 79.03° attributed to cerium oxide phase. The particles have an ordered structure as indicated by the sharp diffraction peaks. The lattice parameter (a0=5.41 ˙A) is similar to reported for CeO2 (a0=5.41 ˙A) in the standard data (ICSD 072155), and its corresponding interplanar distance (d) and crystallite size (D) are 0.31 nm and 13.50 nm, respectively. These values are close to those reported by Andreescu et al. [53], Phoka et al. [54] and Murugan et al. [9]. No other phases were detected indicating the CeO2 NPs are chemically pure.

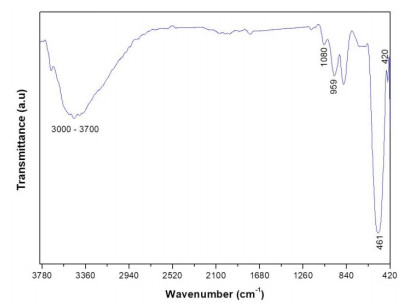

Figure 3 shows the FTIR spectra of the CeO2 nanoparticles. Different signals related to the presence of functional groups can be observed from the spectra. Two bands at 461 and 420 cm−1 corresponding to the Ce-O stretching vibration can be observed. This in agreement with the reports by Calvache-Muñoz et al. [55] and Miri and Sarani [56]. The band at 959 cm−1 could be ascribed to the vibrational stretching mode of H2O [55].

The band at ≈ 1080 cm−1 has been assigned to ν(Ce-O-Ce) vibration [56]. A broad band in the range of 3000–3700 cm−1 is associated to the O-H stretching vibration coming from absorbed water and/or hydroxyl groups [55,56,57].

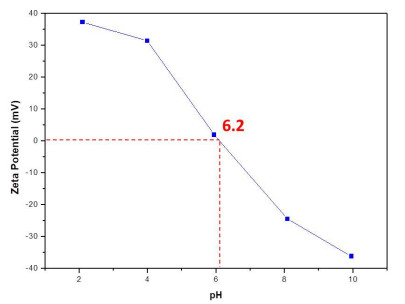

The point of zero charge (pzc) of CeO2 NPs was found at 6.2 (Figure 4). This result is similar to the value reported by Zheng et al. [35] which was 6.7. The pzc can be related with the adsorption capacity of the nanoparticles [35,58]. Consequently, higher adsorption capacity could be expected at lower pH of the solution (pH < pHpzc) because the electrostatic attraction between negative dye molecules and positive charged CeO2 NPs surface [35,58].

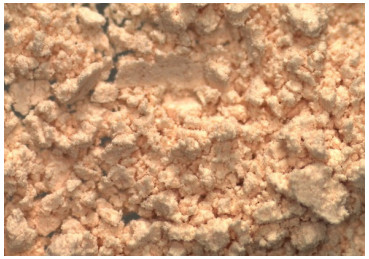

Kar et al. [34], Emsley [59], Singh et al. [60] and Dutta et al. [61] have reported that cerium can exist either in Ce(Ⅲ) or in Ce(Ⅳ) oxidation states, being Ce(Ⅲ) usually colorless and Ce(Ⅳ) turning from yellow to red in color. Accordingly, an approximation to the chemical state of Ce in the particles can be achieved from their UV absorption spectra. In this work the particles had a reddish color as seen in Figure 5.

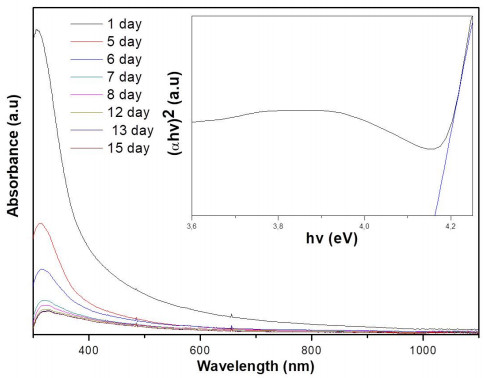

Figure 6 shows the UV-vis absorption spectra of CeO2 NPs as a function of time. The main absorption peak was observed with a shift from 311 nm (day 1) to around 327 nm (day 15). From the day 12 the main absorption peak remained stable (327 nm). Accordingly to Emsley [59], the characteristic absorption peak in the range between 300–400 nm corresponds to Ce(IV) state. This absorption peak is very close to the value (333 nm) reported by Miri and Sarani [56].

The indirect band gap energy (Eg) was calculated as the inset found with the Tauc-plot at the fifteenth day (Figure 6). The band gap energy (Eg) was determined by using the Tauc equation [62]:

Where,

α is the optical absorption coefficient, Eg is the direct band gap, h is the Planck constant, v is the frequency (hv = the photon energy) and A is a constant. The Eg was calculated by plotting (αhv)2 versus hv by extrapolating of the linear part of the curve to the (αhv)2 = 0. The observed band gap energy for CeO2 NPs at the fifteenth day was 4.16 eV. This bandgap value was higher than the value reported by Phoka et al. [54], Atla et al. [57], Mishra et al. [63] (Eg = 2.78–3.44 eV), but lower than reported by Gogoi and Sarma [62] (Eg = 4.91 eV). This increase in band gap value may be due to the charge transition of Ce ion (Ce(IV)) as mentioned by Phoka et al. [54].

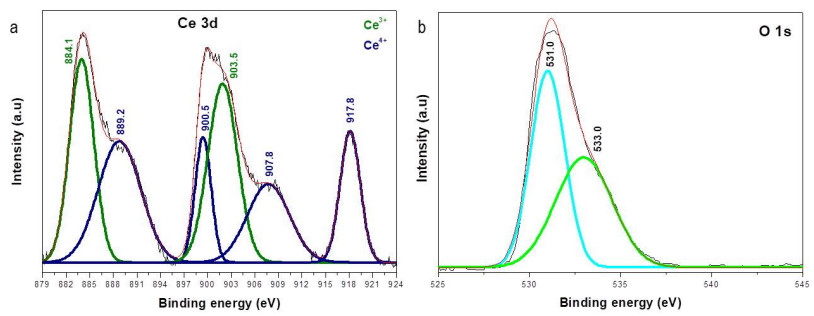

The XPS spectra for the CeO2 nanoparticles of the Ce 3d and O 1s peaks are shown in Figure 7.

Deshpande et al. [51], Tuyen et al. [37], Kumar et al. [17] and Majumder et al. [38] reported the mix of valence states (Ce3+ and Ce4+) in CeO2 nanoparticles and CeO2 thin films. In this work, six characteristics peaks (Figure 7a) of Ce3+ at 884.1 and 903.5 eV, and of Ce4+ at 889.2,900.5,907.8 and 917.8 eV were found. The position of the peaks is according to the other XPS spectra reported in the literature [17,37,51]. These binding energies corresponded with v’, u’, v’’, u, u’’ and u’’’, respectively.

The relative concentration of Ce3+ and Ce4+ was calculated from the deconvoluted curves shown in Figure 7a. The calculations showed that CeO2 NPs have more Ce4+ (56.16%) than Ce3+ (43.84%). Truffault et al. [64] and Majumder et al. [38] have reported that a high relative concentration of Ce3+ and chemisorbed oxygen improved the photocatalytic activity of CeO2.

The XPS profile of O 1s (Figure 7b), evidenced two characteristic peaks attributed to lattice oxygen and chemisorbed oxygen (~ 531 and ~ 533 eV, respectively), as mentioned by Majumder et al. [38], the chemisorbed oxygen is directly proportional to the oxygen vacancies. From the deconvolution the calculated amount of lattice oxygen was 51.77% and chemisorbed oxygen 48.23%.

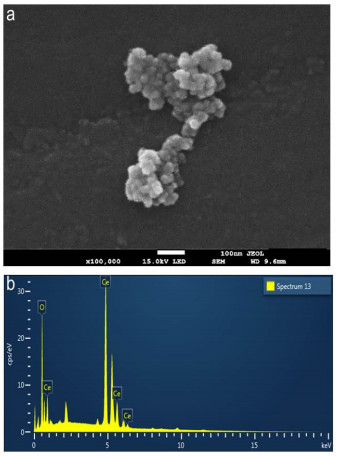

SEM images of synthesized ceria nanoparticles are shown in Figure 8. From this image, it could be observed that the CeO2 NPs exhibit a semi-spherical morphology and considerable agglomeration (Figure 8a, b). This phenomenon has been previously reported. He et al. [49] mentioned in their work that ceria particles tend to form agammaegation.

The EDS spectra confirmed the existence of Ce and O in NPs (Figure 8b). The atomic percentage of each element were 66.42 ± 3.34% and 33.58 ± 3.34% of O and Ce, respectively. This result supports the hypothesis of particles with a stoichiometry near to CeO2. Consequently, the presence of Ce (IV) can be inferred by analyzing together the results from the XPS and EDS.

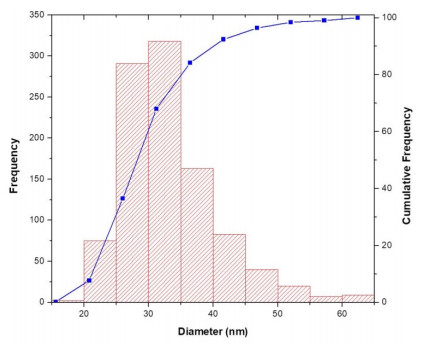

The particle size distribution for CeO2 (Figure 9) showed that the mean nanoparticle size was 33.3 ± 7.3 nm. Besides, the D10, D50 and D90 were 25.2 nm, 31.9 nm and 42.5 nm respectively.

3.2. Photocatalytic activity of CeO2 NPs

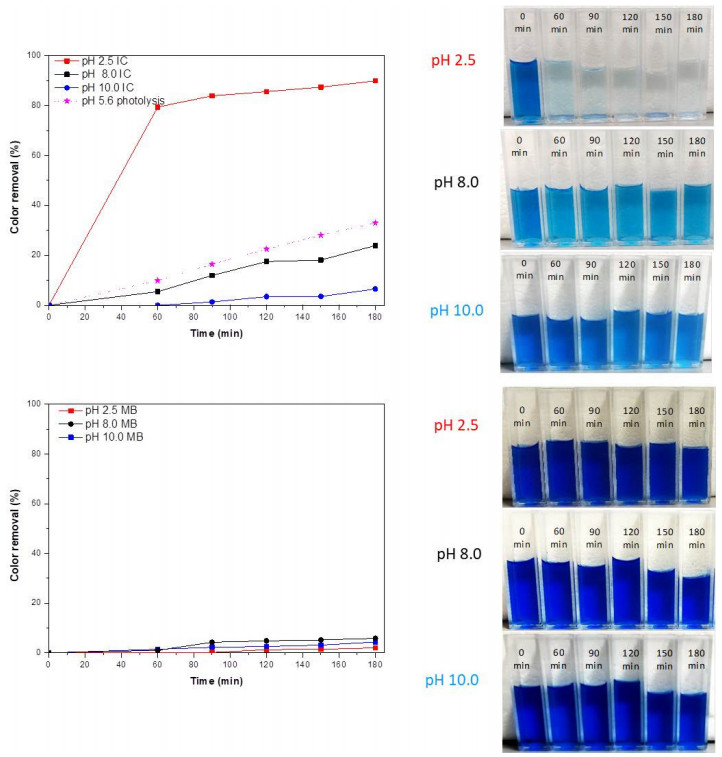

The color removal of IC and MB by CeO2 NPs can be observed in Figure 10. All samples were followed by 180 min and photography of the different solutions are included for the visual inspection. In photolysis conditions, the removal of the IC molecules occurred at a slow rate (33%) within 180 min. Compared with IC solution (pH 2.5), the color removal of the IC (pH 8.0 and 10.0) and MB (pH 2.5, 8.0 and 10.0) solutions were lower.

Some authors have mentioned the heterogeneous photocatalytic oxidation organic pollutants can be explained into five independent steps as follows: (1) transfer of the dye molecules from the liquid phase to the surface of CeO2; (2) adsorption of the dye molecules on the surface of CeO2; (3) the adsorbed dye pollutants react with reactive species in the adsorbed phase, where oxidation and reduction reactions occur once being excited; (4) desorption of the products from CeO2 surface; and (5) removal of the products form the interface region [18,65,66]. Ji et al. [58] also mentioned that the adsorption capacity on photocatalyst of dyes is a key factor for the degradation rate in photocatalytic system. For this reason, to explain the enhanced photocatalytic activity of CeO2 NPs, the adsorption of IC and MB on CeO2 NPs was examined at different pH.

Hao et al. [12] and Vautier et al. [41] have mentioned that photocatalytic oxidation is the main cause for color removal through degradation of chromophore structure. This can be explained by means of two possible mechanisms: a reductive [8] and an oxidative paths [67], that include the cleavage of the chromophore molecule bond. Generally speaking, the photocatalytic degradation of dyes and aromatic pollutants is caused by the degradation of the benzene rings and heteropolyaromatic linkage [39,41,65]. Some authors have shown that the nanoparticles contribute to oxidative cleavage of indigo carmine and consequently, the by-products would include carboxylic acids [10].

The highest color removal was 90%, 24% and 7% (at pH 2.5, 8.0 and 10.0 within 180 min, respectively) for IC, and 2%, 6% and 4% for MB (at pH 2.5, 8.0 and 10.0 within 180 min, respectively). In this case, CeO2 NPs exhibited a poor catalytic performance for IC even after 180 min under UV irradiation at pH 8.0 and 10.0, since the photocatalytic reaction take place in the third step (adsorbed phase). However, these results indicate the ceria NPs could be used as catalyst to photocatalytic degradation of IC dye at pH 2.5, enhancing the color removal about 2.72 times compared to photolysis conditions.

This behavior can be attributed to the electrostatic attraction between dye molecules and charged ceria NPs surface according to the results of Ji et al. [58] and Zheng et al. [35]. In aqueous solution, anionic dyes carry a net negative charge due to the presence of sulphonate groups (SO3-), while cationic dyes carry a net positive charge due to the presence of protonated amine or sulfur containing groups [67,68,69], and thereby, adsorption of anions is favored at pH < pHpzc, while the adsorption of cations is favored at pH > pHpzc. Therefore, a higher color removal capacity could be attained for IC at lower pH of solution (pH = 2.5 < pHpzc = 6.2) because the electrostatic attraction between negative dye molecules and positive charged ceria nanoparticles surface. Hence, a lower color removal capacity was attained for IC at higher pH of solution (pH = 8.0 or 10.0 > pHpzc = 6.2) even compared to photolysis conditions, because the electrostatic repulsion between negative dye molecules and negative charged ceria nanoparticles surface.

Is important to highlight that some authors have mentioned the CeO2 can be easily regenerated by a heat treatment (673 K in air for 2 h) and it can be reused even after four cycles, demonstrating good stability and reusability [35]. Majumder et al. [38] found that the photocatalytic efficiency of the CeO2 remains almost the same after three consecutive cycles which indicates its high stability.

A similar behavior was observed for MB at pH 2.5 (electrostatic repulsion); however, for MB at pH 10.0 greater color removal capacity was expected, but it was inhibited because hydroxyl ions compete with dye molecules in the adsorption process on the ceria nanoparticles surface, as mentioned by Pouretedal and Kadkhodaie [39]. Previous studies have indicated that there is still a controversy about the effect of using CeO2 in the MB dye degradation as shown in Table 1.

This research confirmed that CeO2 NPs exhibits a poor catalytic performance even after 120 min under UV irradiation, in accordance with Miyauchi et al. [36], Tuyen et al. [37], Kumar et al. [17] and Majumder et al. [38]. However, as mentioned by Majumder et al. [38], the degradation of MB could be increased because of higher photocatalytic activity of CeO2 NPs (containing higher percentage of Ce3+ ions and oxygen vacancies that decrease the band gap). Thus, CeO2 NPs may be more easily photoactivated and suitable for removal of cationic dye effluents.

4.

Conclusions

Based on the experimental results of this research, the following conclusions are drawn:

➢ Ceria nanoparticles photocatalyst was synthesized by sol-gel method and they were used for color removal indigo carmine and methylene blue dye solutions at different pH under UV irradiation.

➢ The color removal performance was strongly affected to the electrostatic attraction between dye molecules and the charge at the surface of ceria nanoparticles.

➢ CeO2 NPs exhibit more color removal for IC dye (≈ 90%, 24% and 7% at pH 2.5, 8.0 and 10.0 within 180 min, respectively) compared to MB dye (≈ 2%, 6% and 4% at pH 2.5, 8.0 and 10.0 within 180 min, respectively).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Grupo de Investigación en Materiales Avanzados y Energía MATyER (Advanced materials and energy research group (MATyER)) of Instituto Tecnológico Metropolitano de Medellín (Metropolitan Technological Institute from Medellín) and the Centro Administrativo de Ciencia, Tecnología e Innovación (Department of Science, Technology and Innovation; COLCIENCIAS-Colombia) and its program of Postdoctoral research stay No. 811 for all their support. The authors would also like to acknowledge J.A.C Cornelio for proving support for XPS measurements.

Conflict of interests

All authors declare no conflicts of interest in this paper.

DownLoad:

DownLoad: