1. Introduction

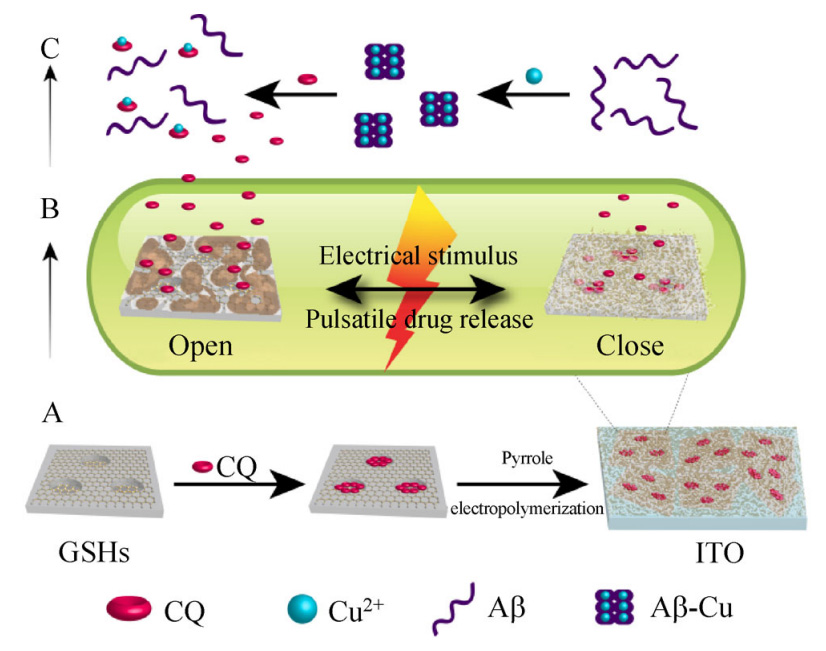

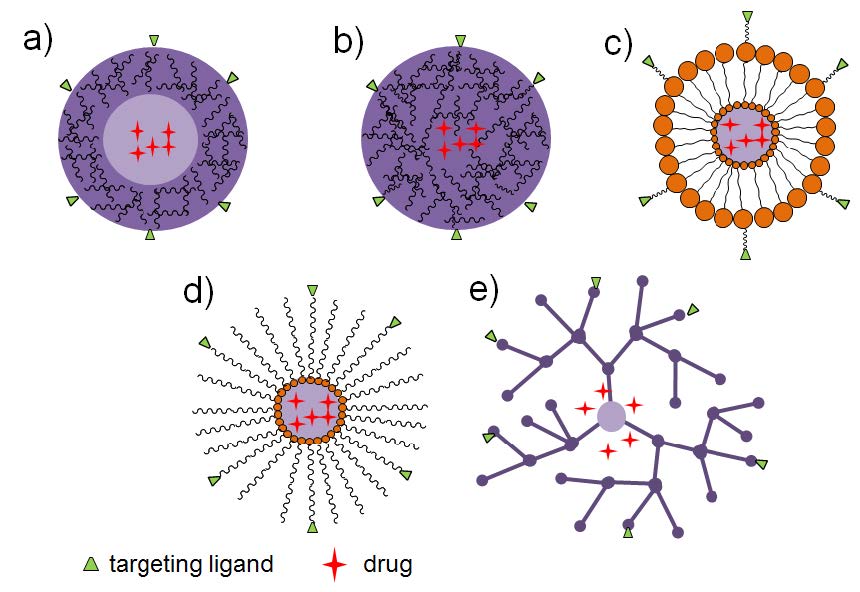

Polypeptide-based nanoparticles have an increasing number of applications in nanomedicine due to their biodegradability and capability to be sensitive to external stimuli. For example, changes of the environmental pH when amphiphilic peptides are employed. Therapeutic drugs can be easily encased into nanoparticles or adsorbed at their surface leading to clear advantages with respect to the use of non-encapsulated conventional drugs. These advantages include: enhanced stability, controlled and triggered release when stimuli responsive polymers are involved, increased biocompatibility, and improved therapeutic effect since a high amount of drug can reach the target site. Different kinds of polypeptide-based nanoparticles can be considered for drug delivery applications (Figure 1): nanospheres, dendrimers, nanocapsules, liposomes and polymeric micelles (polymersomes). Block copolymers can be designed to have a great capability to assemble into vesicles and hydrogels with unique properties. Most of these may also be a consequence of the possibility of blocks to adopt the typical ordered conformations of polypeptides. Furthermore, stimulus-responsive functionalities can easily be given, increasing the potential applications in medical uses [1].

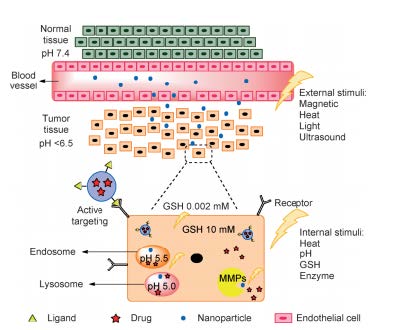

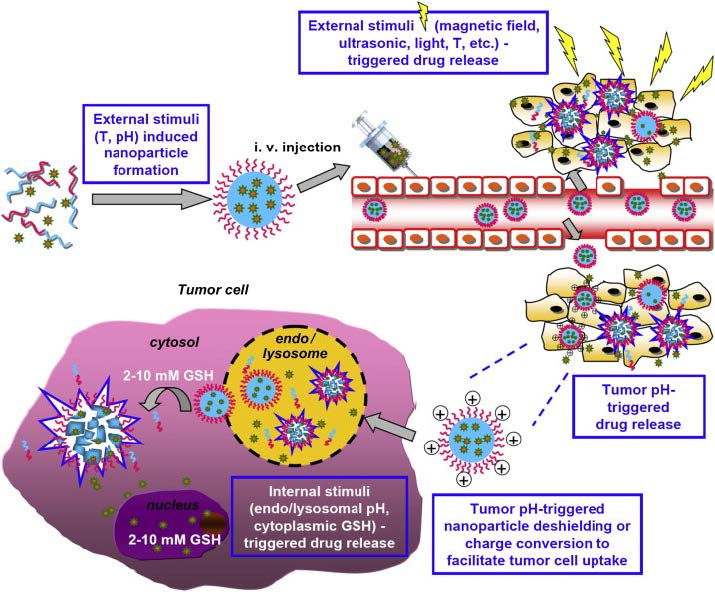

Crucho has recently performed an excellent review concerning the design and formulation of stimuli-responsive polymeric nanoparticles (NNPs). Factors including: pH, temperature, magnetic field, ultrasound, and light can be appropriate stimuli to trigger drug delivery to target cells (Figure 2). In general, polymers should be able to undergo fast changes in characteristics like shape, solubility, swelling, dissociation, and surface [2,3,4,5,6].

Development of nanoscale delivery systems has received increasing attention and great progress has been made on the targeted delivery of anticancer drugs such as doxorubicin and paclitaxel [7]. Application of these new systems is still problematic due to different weaknesses that should still be improved including [8,9]: a) Difficulty to reach the minimal effective concentration at the target site due to limited drug loading capacity, b) Difficulty to get an appropriate release rate (slow in the bloodstream and fast in the targeted cancer cells), c) Low in vivo stability since micelles disintegrate as a consequence of their dilution in the bloodstream (i.e. a concentration less than the critical micelle concentration is attained).

This review is focused on systems based on polypeptides for exclusive applications in the biomedical field. Polypeptides provide different advantages, in addition to those previously indicated, like [10]: a) A rich repertoire of biologically specific interactions, b) Environmentallyresponsive behaviors, c) Capability to self-assemble, d) Control over biodegradation routes and e) Possibility to combine different functionalities.

It is also well established that polypeptides can undergo secondary structural changes as a response to external stimuli (e.g. temperature, solvent, pH, and surfactant). Initial studies were performed with poly(g-benzyl-L-glutamate) (PBGL) and poly(L-lysine) taking advantage of the capability to undertake a helix-coil transition [11,12,13]. Deprotection of side chains of the PBLG may lead to the occurrence of pH dependent conformational transitions. These stimuli responsive polypeptides can be attached to the surface of silica beads giving rise to hybrids that could be considered similar to protein-caged viruses and even used for therapeutic purposes.

Soliman et al. have performed a highly interesting review [14] concerning the capability of polycations to be associated with oppositely charged nucleic acids (DNA, RNA and oligonucleotides) by electrostatic interactions. The condensation process lead the formation of complexes or ‘‘polyplexes’’ that can be easily transported in biological media and across cell membranes to the cytoplasm, giving rise to a great potential for gene and related therapies.

The impact of polypeptide composite particles (PCPs) based around a silica core has recently been reviewed by Rosu et al. [15]. These hybrids have great limitations when being used as platforms for targeted applications.

Copolymers containing at least one polypeptide block are interesting due to their ability to hierarchically assemble into stable ordered structures [16]. Blocks of cationic and anionic polypeptides can be combined with biocompatible polyesters and polyethers to form amphiphilic copolymers which, in turn, could be self-assembled into aggregates like polymeric vesicles (polymersomes), or cylindrical and spherical micelles which are useful for biomedical applications. Polymersomes have fluid-filled cores with walls that consist of entangled chains [17], which separate the core from the outside environment. The weight fraction and molecular weight of the hydrophilic block, and the interaction parameter between the hydrophobic block and water determines the type and form of aggregate that could be produced [14]. Tubular polymersomes, for example, are also interesting since they have delayed internalization kinetics, long circulation times and excellent tumor targeting ability [19,20].

Quadir et al. [21] have recently reviewed the efforts focused to the incorporation of substituent groups of diverse chemical nature in synthetic polypeptides by means of click chemistry. In this way, facile routes to design tunable and responsive polypeptide architectures have been highlighted.

2. PH-Responsive Polymers Based on Polypeptides

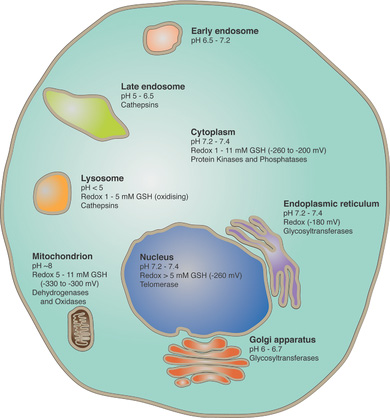

Extracellular pH is relatively constant (i.e. usually between 7.2 and 7.45) but it can drop as low as 6.4 in tumors [22,23] since cancer cells can metabolize glucose utilizing a patway that produces lactate [24]. This difference is an interesting potential way to induce a selective drug release, but obviously materials would need to respond to a very narrow pH range. This is not the case, for the intracellular pH which can vary significantly between the different parts (e.g. from 4 to 8) (Figure 3). Materials can enter into cells via endocytosis leading to a fast acidification to a pH between 4.5 and 5.5. Proton pumps and channels of endosomal membranes allow the acidification to occur which implies the pumping of counter ions to keep the charge balance and the diffusion of water to maintain the osmotic pressure. In any case, acidification can be exploited to activate the release mechanism.

Most of pH sensitive polymer systems are based on polyelectrolites since they can be ionized under the appropriate pH causing the solubilization or an expansion of their typical coiled coil conformation [25]. In this way, ionizable groups can be attached to the polymer backbone (e.g. peptides having glutamic and aspartic acid residues that become sensitive to low pH values and peptides having lysine, histidine and arginine units that are sensitive to basic pHs). Polymers can also bear pH-sensitive bonds whose cleavage causes the release of drugs attached to the polymer backbone [26].

Anionic peptides containing carboxylic groups, such as poly(aspartic acid) (PAA) and poly(glutamic acid) (PGA) are widely employed as pH-sensitive polymers. These polymers are protonated at low pH and their backbones become relatively hydrophobic, while they are deprotonated at neutral or high pH and consequently become hydrophilic [27].

Cationic peptides such as polylysine (PLys), polyhistidine (PHis) and polyarginine (PArg) have positively charged amino groups on each monomer at low pH. This feature confers a hydrophilic character and a unique condensing gene feature for acting as ideal gene carriers [28].

Amphiphilic copolymers can be obtained from anionic or cationic peptides by joining them with hydrophilic polymers such as PEG. As previously indicated, these amphiphilic copolymers can be self-assembled into micelles, nanoparticles, and vesicles depending on the final composition. Nevertheless, solvent also plays a relevant role since compact vesicles are favoured when the dipole moment of the solvent is low. In this case, shrunken, rodlike peptidic helices are packed side-by-side along their long axes to form a compact vesicle.

Amphiphilic copolypeptide systems based on polyleucine and polylysine blocks were able to form vesicular membranes and even hydrogel networks [29,30]. Nevertheless, the presence of highly charged polypeptide segments (e.g., poly(l-lysine)) distorted the membranes due to repulsive polyelectrolite interactions. Therefore, similar diblock copolymers with shorter charged segments (i.e. poly(l-lysine)20-80-b-poly(l-leucine)10-30 and poly(l-glutamic acid)60-b-poly(l-leucine)20) were studied by Holowka et al. [31] in order to get stable charged polypeptide membranes.

Assembling of the zwitterionic diblock copolymer of poly(L-glutamic acid) and poly(L-lysine) (PGA-b-PLys) gave rise to reversible polymersomes [32], which self-assembled under both acidic (pH < 4) and basic (pH > 10) conditions. At low pH PLGA was protonated causing a decrease in solubility and the stabilization of a compact helical (“rod”) structure. The increased hydrophobicity drove the self-assembly of polymersomes. PGA formed the core while PLys block exhibited a b-sheet structure with a good solubility and formed the shell. Under basic conditions, a solubility change was observed as well as a structure reversion which means that PGA and PLys formed the shell and the core, respectively.

PEG-polypeptide copolymers with amine pendant chains have been synthesized by click chemistry to generate materials that can be self-assembled as vesicles and used as effective pH sensitive drug carriers. Synthesis was carried out by combining typical N-carboxyanhidride ring opening polymerization with post-functionalization using azyde-alkyne cycloaddition. Specifically, these nanosized vesicles were stable platforms for delivery and could be successfully localized in solid tumors to release doxorubicin (DOX) through the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect and the lowered pH of the tumor microenvironment [33].

Amphiphilic AB2 type miktoarmpolymershave a greater ability to form vesicles than do typical diblock copolymers [34] and furthermore, appear more appropriate to mimic the complex architectures of natural phospholipid bilayer vesicles. Taking into account these concepts Yin et al. [35] synthesized a histidine-based AB2-miktoarmpolymer(mPEG-b-(polyHis)2) that displayed aphospholipid-mimic structure, low cytotoxicity, and pH-sensitivity. Below pH 7.4 the polymersome shape changed progressively from cylindrical micelles, to spherical micelles, and finally to unimers. The pH decrease lead to an increasing hydrophilic weight fraction that could help to disrupt the endosomal membrane throughproton buffering. Furthermore, this biocompatible histidine-based miktoarmpolymer was revealed as an appropriate pH-sensitive drugdelivery system.

Several drugs can be loaded into the albumin-based carriers since albumin utilizes different binding sites [36]. In addition, albumin shows ideal characteristics like in vivo stability, easy uptake in tumor tissues, nonimmugenicity, and nonantigenicity together with absorbability, biodegradability and biocompatibility [37,38]. Along these lines, DOX was attached to the bovine serum albumin (BSA) via a pH-sensitive linker, cis-aconitic anhydride (CAD), which was able to be hydrolyzed in the acidic lysosomal environment and to provide a pH-responsive release of the anti-cancer agent. Folic acid (FA) was also linked to albumin in order to increase the selective tumor-targeting ability of the conjugate [39]. The selective targeting efficiency of FA is well known since a folate binding protein, (i.e. a glycosylphosphatidylinositol [40]) is over-expressed in human tumors (e.g. ovary, uterus, brain) while has limited expression on normal cells [41].

Semi-IPN porous networks based on hyaluronic acid (HA) and poly(aspartic acid) (PAS) have recently been prepared and characterized [42]. Intermolecular interactions between both polymers were detected by FTIR as well as the poly(aspartic acid) inclusion into the meshes of the network derived from crosslinking of HA withdivinyl sulfone (DVS). The physical links between the functional groups of HA and PAS increased the thermal stability, while the presence of PAS into the HA gel network gave rise to acidic pH sensitivity and also a high swelling capacity.

3. Thermally-Responsive Polymers Based on Polypeptides

A local hyperthermia may lead to an aggregation of peptide molecules and the subsequent accumulation of these carriers in the tumor vasculature. Peptides dissolve once returned to normal temperature giving rise to a high local concentration and extravascular accumulation of the carrier. Mild hyperthermia (37-42 ºC) may favor drug delivery into tumor cells since these are more sensitive to damage induced by an increase of temperature and vascular permeability in such a way that the anti-tumor effect becomes enhanced.

The most widely studied thermally responsive peptides are leucine zippers, elastin-like polypeptides (ELPs), collagen, and silk[43,44].

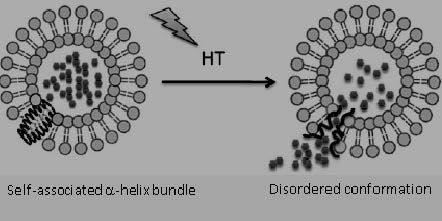

Leucine zippers are involved in the dimerization of several transcription factors [45] and correspond to coil intertwining of helices with a characteristic seven-residue repeat sequence [46]. These zippers are stable at low temperature but can dissociate at a determined temperature that can be controlled by means of the specific peptide sequence. In this way, different thermoresponsive systems for drug delivery have been proposed, including systems that take advantage of the capacity to prepare switchable hydrogels [47]. Leucine zipper peptides have successfully been incorporated into lipid bilayers during liposome preparation, giving rise to hybrids able to deliver high levels of anti-cancer drugs like DOX after localized mild hyperthermia [48] (Figure 4).

Advanced functional hydrogels can be prepared from BAB triblock copolymers constituted by two terminal polypeptide domains characteristic of the coiled-coil motif and a central polyelectrolite domain. A reversible gelation was observed under suitable pH and temperature conditions due to the balance between the oligomerization of the helical ends and the swelling of the central polyelectrolyte domain [49].

Silk-elastin-like protein polymers (SELPs) are constituted by a silk-inspired hexapeptide (i.e. GAGAGS) and pentapeptide sequences based on silk and elastin, respectively. At high temperatures the valine residues of the elastin sequence form intermolecular hydrogen bonds. Therefore, a conformational change from an initial hydrophilic random coil to a hydrophobic b related structure takes place, and an agglomerated state is derived. This thermally reversible process has been integrated into plasmonic gold nanostructures that can lead to optically responsive materials [50]. Amino acid repeats of [(GVGVP)4(GGGVP)(GVGVP)3(GAGAGS)4] have been prepared by DNA recombinant techniques, resulting in a conformational change between 50 and 60 ºC as a result of self-assembly behavior and the structural stabilization provided by the β-structure-forming silk-like blocks [51].

Elastin-like polypeptides can be genetically encoded and consequently, a great control over molecular weight and sequence is feasible. The first one is meaningful since it can control pharmacokinetics while the second may control the biodegradation and can be designed to give biological activity such as the targeting to specific cell receptors [52].

Drug delivery based on polymeric carriers is of great interest in cancer treatment since these systems have an EPR effect in solid tumors and consequently display improved pharmacokinetics with respect to free drugs [53]. In addition, these polymer-based carriers can enter more efficiently into tumor tissues than into normal tissues. Efforts are now focused on endowing a stimuli responsive character that allows targeting the polymeric carrier to the tumor [54].

Raucher et al. have developed a thermally responsive elastin-like polypeptide (ELP) [55,56] that has been employed for thermally targeted delivery of anti-cancer drugs as DOX and other therapeutic peptides. Basically, ELPs have a phase transition at a temperature (Tt) that depends on polymer concentration and polymer hydrophobicity. The polymer is soluble in aqueous media at temperatures below Tt and forms aggregates at higher temperatures than Tt. Aggregates can be accumulated and consequently the local concentration of the cargo becomes increased. A great advantage of the proposed polypeptide is the capacity to modify the chain length and composition of the pentapeptide repeat sequence (Val-Pro-Gly-Xaa-Gly, where Xaa is any amino acid different from proline) since it is genetically engineered [57]. ELPs with a Tt slightly higher than the physiological temperature (e.g. close to 40 ºC) are ideal to avoid problems related to necrosis of tissue surrounding the heated tumor [58], in which vascular permeability is expected to increase as well as the penetration of the ELP polypeptide. Chilkoti et al. reviewed up to four applications of ELPs to drug delivery, with the mechanisms of such systems designed to take advantage of the relationship between Tt and the body temperature [59]. They also pointed out new potential applications such as providing an appropriate design to respond to small (<1) pH differences that exists between normal tissue and solid tumors, and the larger pH differences that can be found between the cytoplasm and the endo-lysosomal compartments within cells.

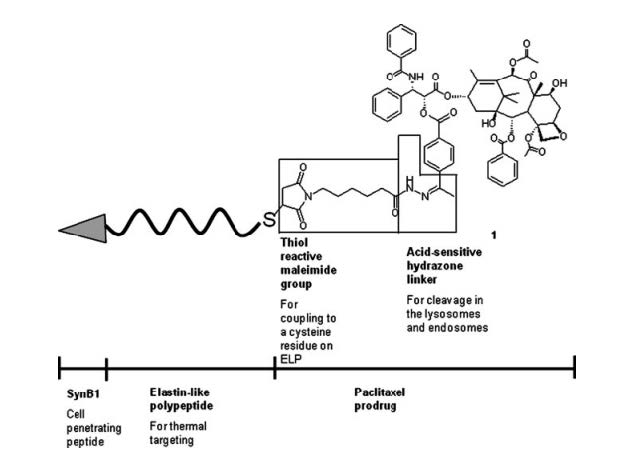

The use of ELPs also appears interesting for water insoluble anti-cancer drugs like paclitaxel. An ELP (Figure 5) having both thermo- and pH-sensitive responses has currently been developed for promoting the intracellular delivery of paclitaxel [60]. This molecule was coupled to the ELP through a hydrazine bond that could subsequently be cleaved at the acidic pH of lysosomes and endosomes. In addition, the N-terminus of ELP was modified to contain a cell penetrating peptide by adsorptive-mediated endocytosis (CPP) [61].

The local concentration of paclitaxel caused by the aggregation of ELP increased cytotoxicity and apoptosis of even resistant breast cancer cell lines.

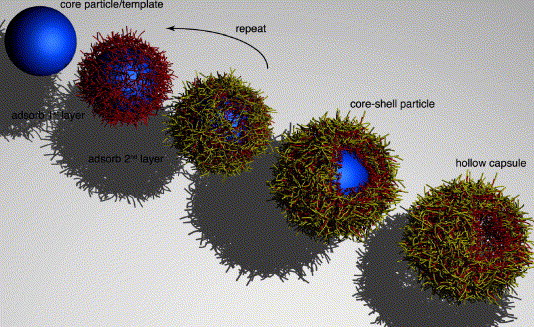

Multilayer architectures with nanometric precision with a wide range of electrical, magnetic, and optical properties can be prepared using layer-by-layer (LbL) electrostatic self-assembly of charged polymers [62,63]. LbL assembly can be achieved by the alternating exposure of a charged substrate to solutions of positively and negatively charged electrolites. The multilayered structure stabilized by electrostatic forces can also be applied to curved surfaces of sacrificial colloidal particles, which can be subsequently removed giving rise to micro- and nanosized capsules (Figure 6). These capsules could be sensitive to external stimuli and therefore appear as promising new drug delivery vehicles. Furthermore, the external surface of capsules can for example be pegylated to increase their colloidal stability [64] or functionalized with ligands for targeting specific cells [65].

Thermoresponsive multilayer films consisting of ionic elastin-like peptides have been prepared via LbL assembly [66]. Peptides containing lysine and glutamic acid units were employed as polycation and polyanion, respectively. The application of monodisperse peptides of similar main chain and equidistanced charged moieties led to stable films at biologically relevant pHs despite the limited number of charged groups. Furthermore, these multilayered films were temperature-responsive around the physiological temperature.

Linear ELPs have limitations derived from their broad-phase transitions and large hysteresis that were caused by the strong hydrogen bonding interactions established between their amide groups. Therefore, other thermoresponsive polypeptides with different chemical structures or architectures have been developed. These systems are mainly based on the interactions that take place in an aqueous polymer solution and define the lower critical solution temperature (LCST). Below this temperature polymers are soluble, and above the LCST they become increasingly hydrophobic and form aggregates. The abrupt change in solubility, which is governed by the free energy of mixing, is a response to the variation of temperature. Basically, oligopeptides or polypeptides with thermoresponsive properties can be achieved through covalent modifications that allow tuning the hydrophilic/hydrophobic ratio [67].

Different nonionic functional polypeptides with tunable thermoresponsive properties have been prepared by grafting oligo(ethylene glycol) (OEG) chains. Poly(glutamate) having OEG side-units were found to be able to adopt ordered secondary structures depending on the length of the OEG units [68]. The LCST in aqueous solution of these copolymers could be easily tuned by varying OEG length and the ratio of the comonomers. Therefore, the thermoresponsive characteristic of OEG units could be retained. Namely OEG units were still able to form hydrogen bonds with water and exhibit reversible dehydration and hydration with variation of temperature.

Poly-L-cysteine having OEG side chains displayed different solubility and secondary structures in water depending on the length of the OEG side chain. These nonionic polypeptides displayed reversible thermoresponsive properties in water when the number of ethylene glycol units was between 3 and 5 [69].

Monodispersed oligoprolines decorated covalently with hydrophobic units showed characteristic thermoresponsive behavior with fast and sharp phase transitions at certain concentrations [67]. The phase transition temperatures were dependent on the shape and location of the hydrophobic units and could be tunedviasupramolecular host-guest interactions.

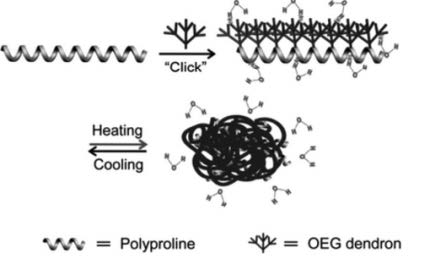

Helical dendronized polyprolines of high molecular weight showed thermally-induced phase transitions that were dependent not only on the dendron generation but also on the arrangement of the dendrons along the polyproline backbone [70]. Polymers were prepared by attaching OEG dendrons onto the main polyproline chains through click reaction (Figure 7).

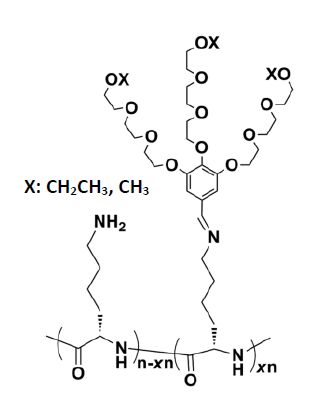

Yan et al. [71] have proposed the use of dynamic covalent chemistry (DCC) to get thermoresponsive polypeptides with dynamic characteristics. In fact, several polypeptides have found applications as receptors, via self-replication and responsive assembly through the use dynamic covalent linkages such as acylhydrazone, imine and disulfide [72,73,74]. New thermoresponsive polypeptides (Figure 8) were prepared through dynamic imine linkage via reactions of amino moieties from poly(L-lysine)s with aldehydes from oligoethylene glycol (OEG)-based dendrons [71]. Differences in thermoresponsiveness were attained due to imine dynamic covalent linkages, making it possible to tune the phase transition temperatures by varying the ratio of OEG dendrons with different hydrophilicity. Interestingly, the attachment of dendrons enhanced the stabilization of the polypeptide helical conformation, which in addition could be reversibly switched through thermally induced aggregation.

Gelatin is a typical hydrogel constituted by proteins which shows a thermally induced phase transition and has potential applications as a drug delivery system [75]. Advantages of gelatin are its biodegradability, biocompatibility and also the capacity to be modified as discussed below. A random coil conformation at sol state is found at temperatures higher than 30 ºC, and upon decreasing the temperature below 25 °C, the gelatin solution solidifies, and a continuous network is formed by partial helix formation [76].

Hydrogels composed of gelatin and the diblock copolymer monomethoxy poly(ethylene glycol)-b-poly(D, L-lactide) (MPEG-PDLLA) diblock were foundto be able to form gels at a narrow temperature range between body temperature and room temperature [77]. The incorporation of a diblock copolymer, featuring a LCST, into the gelatin hydrogel could modify its thermal behavior giving rise to appropriate materials for biomedical uses.

Gelatin is also usually grafted with other polymers that exhibit thermogelation upon heating since it is the usual requirement for polymers to be used for biomedical applications. Gelatin grafted with poly-N-isopropylacrylamide (pNiPAAm) showed a thermoresponsive character and improved cell proliferation when the pNiPAAm:gelatin weight ratio was above 5.8 [78]. A higher gel porosity that provided a favorable cell environment occurred at 37 °C.

The design of polypeptide-based formulations that undergo liquid to hydrogel transitions upon change in temperature is receiving increasing attentionsince these hybrid copolymers can be mixed with cells or injected into tissues as liquids, and subsequently transformed into rigid scaffolds or depots. Hybrid block copolymers constituted by PEG and a polypeptide have been widely considered [79,80,81,82] since the formation of a hydrogel by raising the temperature can be achieved by both, the dehydration of PEG segments and the arrangement of polypeptide short segments into b-sheet structures via intermolecular hydrogen bonds. Polypeptides modified with PEG side chains have also been described as thermoresponsible hydrogels [83].

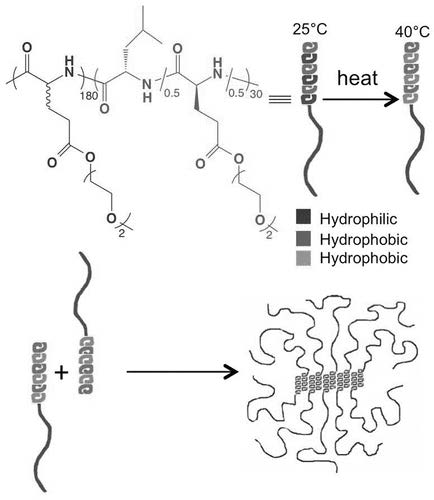

Nonionic diblock copolypeptide hydrogels materials with highly reversible thermal transitions and tunable properties have been prepared by combining hydrophilic poly(γ-[2-(2-methoxyethoxy)ethyl]-rac-glutamate) and hydrophobic poly(L-leucine) segments [84]. These nonionic and thermoresponsive hydrogels (Figure 9) were found to support the viability of suspended mesenchymal stem cells in vitro and were able to dissolveand provide prolonged release of both hydrophilic and hydrophobic molecules.

4. Redox Responsive Polymers Based on Polypeptides

Bioactive polymersomes fully based on amino acid and carbohydrate building blocks represent a new step to mimick natural vesicles. These block copolymers can be easily synthesized; for example by a sequential ring-opening polymerization of benzyl-L-glutamate (PBLG) and propargylglycine N-carboxyanhydrides followed by a glycosylation using azide-functionalized galactose [85]. The use of synthetic polymers was in this case omitted, whereas a fully biocompatible system was derived. New copolymers could be self-assembled by nanoprecipitation giving rise to controlled morphologies that varied from worm-like micelles to polymersomes depending on the composition and the precipitation protocol. The presence of carbohydrates in the surface of the synthesized nanoparticles appears highly interesting to promote cell interaction and recognition, whereas the hydrophobic PBLG tends to adopt a helical conformation that enhances the formation and stabilization of vesicles [31].

A structure similar to that of a glycoprotein was also reported by Schatz et al. [86] by synthesizing copolymers from natural polysaccharides and polypeptides. Specifically, the amphiphilic dextran-block-poly(γ-benzyl-L-glutamate) was found to be able to self-assemble into small vesicles that could be used as a new generation of drug- and gene-delivery systems with a high affinity for the surface glycoproteins of living cells and with high similarity to viral capsids.

Poly(γ-benzyl-L-glutamate)-block-dextran (PBLG-b-dextran) copolymers were effectively crosslinked with 3,3′-dithiodipropionic acid (DPA) giving rise to redox-responsive micelles [87]. The reductive environment characteristic of intracellular conditions was able to dissociate the disulfide crosslinks into free thiols. DOX as a model anticancer drug was loaded into the shell of the crosslinked micelles and an accelerated release in the presence of glutathione (GSH) was observed along with inhibition of cellular proliferation when the intracellular GSH level was increased by an appropriate cell treatment. In fact, the presence of GSH is one of the most significant difference between a normal tissue and tumor cells. An extensive review concerning the synthesis strategies for preparing drug delivery systems based on polymers containing disulfide bonds has been reported by Liu and Liu [88].

The triblock copolymer poly(ethylene glycol)-b-poly(L-cysteine)-b-poly(L-phenylalanine) (PEG-PCys-PPhe) was able to self-assemble to form micelles in aqueous solutions and to self-cross-link (SCL) by the oxidation of thiol groups in the PCys segments [89]. The in vitro drug release in response to GSH was also studied. It was found that the cross-linking reduced the drug loss in the extracellular environment under reductive conditions (e.g. that provided by GSH), the release was accelerated due to the cleavage of disulfide bonds. The glutathione-responsive micelles could be easily taken up by cancer cells like HeLa cells, opening a great potential in intracellular drug delivery and the treatment of tumors.

Recently, greater efforts are focused for the delivery of gene-encoding sequences into different stem cells types. An efficient system appears to be the formation of DNA complexes with cell penetrating peptide ligands that bind receptors expressed on the cell surface. Beloor et al. [90] have proposed a 29 amino acid long peptide, RVG, to bind both human embryonic (hESC) and mesenchymal (hMSC) stem cells through the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. Nanoparticles incorporating plasmid DNA were subsequently prepared by conjugating RVG to a redox-sensitive biodegradable arginine-grafted dendrimer to get an environment-sensitive DNA release and a reduced cytotoxicity due to the high polymer degradability. Redox-sensitivity was a consequence of the presence of several internal disulfide bonds in the grafted polymer that could be reduced in the glutathione-rich environment of the cytoplasm eliciting effective release of complexed nucleic acids.

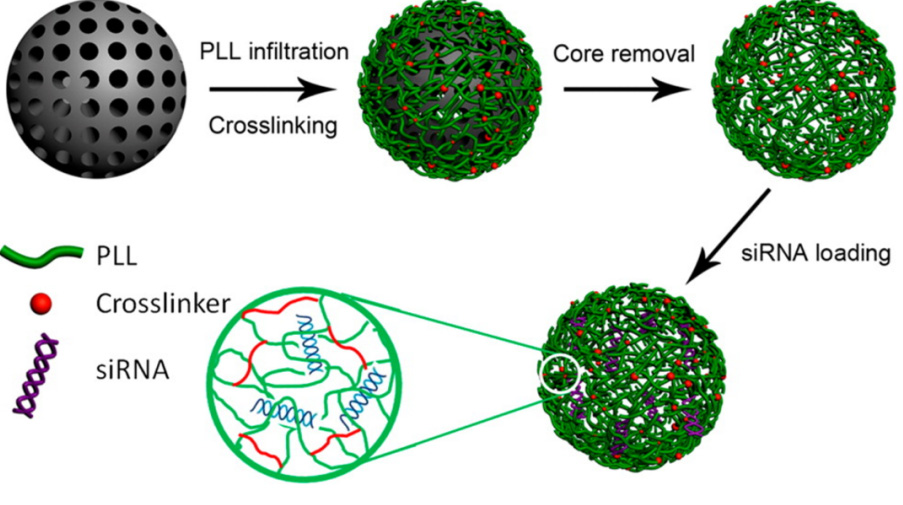

Small interfering RNA (siRNA) can silence disease-causing genes and consequently the use of such agents appears to be a promising alternative for cancer treatment despite their low bioavailability [91,92] (Figure 10). The net negative charge and relatively large size of synthetic small siRNA hindered the capability to cross biological barriers and furthermore their duplexes are quickly degraded by serum and intracellular ribonucleases. To avoid these problems Cavalieri et al. [92] designed redox-responsive nanoporous poly(ethylene glycol)-poly-l-lysine particles, NPEG-PLLs, using mesoporous silica (MS) as sacrificial porous templates [93].

Basically, MS particles were incubated in a PLL solution and then reacted with PEG-NHS-disulfide cross-linker. The MS templates were finally dissolved with a buffered solution to encapsulate siRNA with a high loading capacity. Bioactive siRNA was effectively released through the reduction of disulfide bonds into the cytosol of prostate cancer cells where nanoparticles were previously targeted through the anti-apoptotic factor, survivin.

Reducible copolypeptides (rCPP) composed of two cationic peptide sequences have also been used to form polyplexes with ADN. Specifically, a nuclear localization sequence (NLS) derived from the SV40 virus was randomly combined via disulfide bonds with histidine-rich peptides (HRP) that provided an endosomal buffering capability. The disulfide bonds in the backbone of the rCPP chains were cleaved in a reducing environment provided by dithiothreitol. As a result, short cationic HRP and NLS peptide residues with lower affinity to the DNA were formed, enhancing the subsequent dissociation of polyplexes [94].

5. Magnetic Responsive Polymers Based on Polypeptides

Magnetizable nanoparticles (e.g., magnetite, iron, iron oxides, copper and nickel) can be incorporated into polypeptides as well as in other biodegradable and biocompatible polymers to get magnetic-responsive materials for targeting drug delivery, contrast agents in magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), magnetic hyperthermia and tissue engineering [95,96,97]. Various techniques have been developed for the preparation of the composite magnetic carriers, including the nanoprecipitation, solvent diffusion and emulsion-solvent evaporation [98,99].

Particles less than about 10-20 nm in diameter render a single magnetic domain, which is associated to a uniform magnetization where all the spins are aligned in the same direction, a high coercivity (i.e. a large magnetic intensity is required to completely demagnetize the material) and superparamagnetic properties [100]. Magnetic particles are frequently used for separation of biomolecules because they can be easily extracted from a sample by applying an external magnetic field. To this end particles arefunctionalized with recognition molecules, such as antibodies or single stranded DNA. Numerous strategies have been developed to immobilize peptides on nanoparticles taking advantage of the chemical versatility of the amino acids and the capability to modify the nanoparticle surface chemistry. Peptides can be directly immobilized by physisorption (i.e. by van der Waals, electrostatic and hydrophobic interactions) or chemisorption, or indirectlytaking advantage of a molecular linker layer previously immobilized on the particle surface.

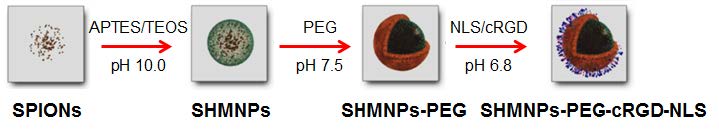

Biocompatible superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles (SPIONs) can be easily prepared with high reproducibility and therefore appear interesting as targeting systems [101]. The surface of these particles should be functionalized with both synthetic polymers like PEG to ensure colloidal stability and targeting peptidic sequences, a feature that may be problematic in terms of yield and particle agglomeration. An alternative based on the incorporation of SPIONs in an amine-functionalized silica matrix has been proposed [102] and a fast response to an external magnetic field verified. Coupling of peptides on these magnetic NPs was achieved through heterobifunctional PEG, which acted as a cross-linker and enhanced colloidal stability, using a microreactor set-up [103] (Figure 11).

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is one of the most powerful techniques to get physiological and anatomic information of tissues. Developments carried out on hyperpolarized species (i.e. those that experienced a physical spin ordering that temporarily enhances nuclear magnetism by several orders of magnitude) are allowing overcoming typical limitations related to the lack of sensitivity. Lerche et al. [104] have reviewed the most importantimprovements leading to noninvasive and selective observation of macromolecules and small molecular probes with enhanced time resolution and sensitivity.

The nuclear spin of xenon can easily be hyperpolarized, being the unique species that can cross a cell membrane passively while keeping more than 90% of its hyperpolarization [105]. The high relaxation time of intracellular xenon and the relatively high exchange time between the inner and outer cell compartments opened new perspectives for cell characterization and even for targeting of cell receptors. In fact, 129Xe NMR spectra of intact cells contain a signal specific to the intracellular compartment that could be different to that associated to the external pool. Interesting applications can also be derived from the different fluidity between normal and tumor cells [105]. Kotera et al. have recently proposed smart bimodal 129Xe NMR-fluorescence probes for tetracysteine tagged proteins in order to facilitate the discrimination of signals coming from the out- and in-cell compartments and obviously to address intracellular events [106].

The design of a new generation of biocompatiblepeptide-based molecular machines with applications in biological systems has recently been proposed by Kwon et al [107]. Application of a static magnetic field allowed the alignment of self-assembled molecular architectures of β-peptide foldamers [108]. The well-ordered molecular packing of the structured foldamers (named as foldectures [109]) showed an amplified anisotropy of the diamagnetic susceptibility and a magnetotactic behaviour at the macroscopic scale in a similar way as magnetosomes in bacteria.These microorganisms are able to align and actively swim along the geomagnetic field due to the nanometer-sized magnetic crystals bound to their cell membrane [110].

6. Ultrasound-responsive polymers based on polypeptides

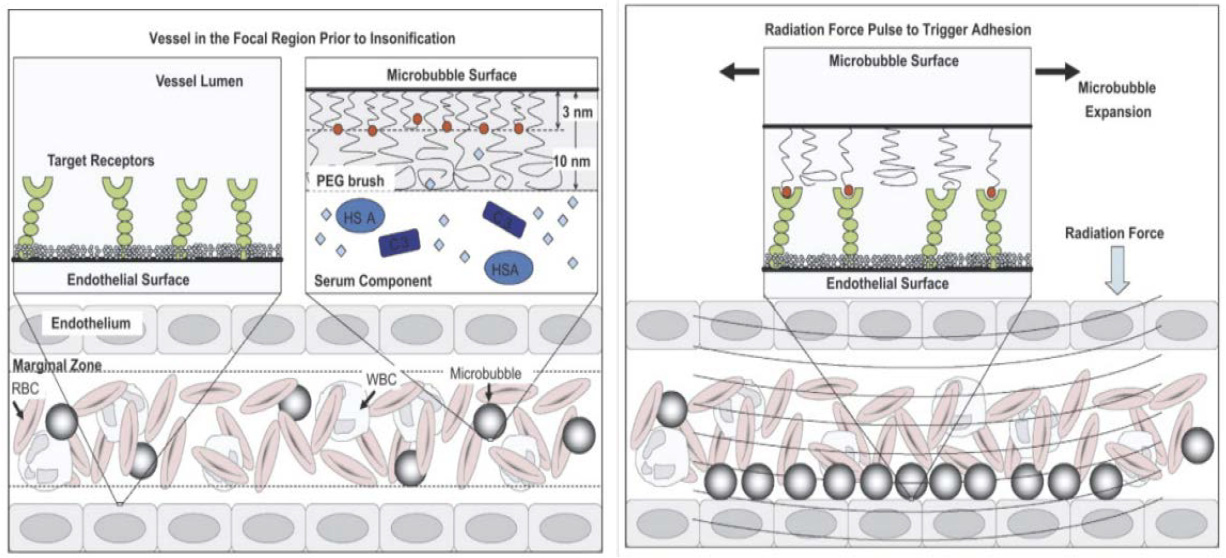

Recent studies have demonstrated the efficiency of ultrasounds as a molecular imaging tool and specifically for molecular targets associated with different processes such as venous thrombosis, angiogenesis and inflammation [111,112,113]. Basically, microbubbles (MBs) comprising a hydrophobic gas and a stabilizing shell are produced. Efficiency of MBs as contrast agents depends on the gas compressibility, dimensions (usually between 1-6 mm), wall thickness, viscosity and density of the bubble shell [114]. Ultrasound parameters such as frequency, intensity, and pulse repetition frequency are also meaningful to favor the inertial cavitation and MBs fragmentation required for penetrating leaky tumors [115].

MBs should have high circulation stability and can be forced to be adhered and broken at the specific site to deposit targeted compounds [116,117]. Borden et al. [118] used a peptide ligand buried by a polymeric overbrush in order to avoid immunogenic response and made feasible the adhesion to specific cells after being released by the application of an ultrasound radiation force (Figure 12).

Air-filled MBs made of poly lactic acid (PLA) that are trapped by a polymer platform having a recognition hexapeptide (i.e. VRPMPLQ) were found highly efficient for detecting malignant regions in the colon epithelium [119]. Polymer shelled MBs can also be loaded with drugs [120,121] such as DOX and fragmented by exposure to ultrasounds. The generated drug-loaded nanoparticles were capable of accumulating within a tumor and providing a sustained release of the drug [115].

7. Enzyme-Responsive Polymers Based on Polypeptides

A useful drug release mechanism can be obtained from peptides able to mimic enzyme substrates and also to link to the appropriate drug. In this way, enzymes that are overexpressed in cancer tissues can be used to activate the release of loaded drugs. Nanocarriers, through receptor-mediated-endocytosis, can enter into cells and internalize to lysosomes where under the action of enzymes (e.g. cathepsin and metalloproteases) can degrade and deliver the loaded drug. The presence of an appropriate peptide sequence between carrier and drug allows for a fast release under the action of the target enzyme.

It is also possible to administer the enzyme after the injection of the polymer-drug conjugate. The enzyme is expected to be accumulate in the tumor tissue due to the EPR effect, in this case a potential limitation is the immunogenicity caused by the incorporation of a foreign enzyme [122].

A functional lipid, which is cleaved by the protease activity of metalloproteinase-2 (MMP-2), was designed for the treatment of hepatocellular carcinomas (HCC) [123]. Specifically, the amino group of dioleoylphosphatidylethanolamine was linked to a PEGylated peptide (Gly-Pro-Leu-Gly-Ile-Ala-Gly-Gln), which was an ideal substrate for MMP-2. The uptake by normal hepatocytes of liposomes containing the designed molecule on their surface was inhibited by steric hindrance. In addition, PEG moieties extended the liposome circulation half-life since their uptake by macrophages was decreased. Interestingly, HCC cells were able to cleave the hybrid molecule, allowing a selective recognition of liposomes by the appropriate receptors of HCC cells.

A Gly-Phe-Leu-Gly peptidewas linked to the carboxylic acid end groups of a dendrimer, which was conjugated to methoxy poly(ethylene glycol) (MPEG) and DOX. The synthesized nanoparticles (size ca. 200 nm) had cathepsin B-sensitivedrugrelease properties due to the sensitivity of the peptide sequence to the cleavage by the enzyme, and consequently this system appears as a promising vehicle for cancer cell targeting due to the over-expression of cathepsin B [124].

Hydrogel microparticles based on PEG functionalized with an enzyme-responsive peptide appear attractive for treatment of pulmonary diseases. These hydrogels can be synthesized with sizes between 0.5 and 5 μm to achieve an efficient deep deposition into the lungs [125], and subsequently can be swelled to reach larger sizes in order to avoid their uptake by macrophages. The efficient encapsulation of three well-differentiated drugs (hydrophobic dexamethasone, hydrophilic methylene blue and a protein based drug) has recently been proven along with a release induced by the presence of MMP-2 [126].

Mesoporous silica nanoparticles (MSNs) are highly employed as controlled delivery systems since they have advantages such as large pore volume and surface area, good biocompatibility, tunable pore sizes, and numerous reactive hydroxyl groups to made feasible a high drug loading efficiency. In any case, it is necessary to prevent a fast drug leakage, by designing, for example, different molecular switches [127,128].

Functionalized mesoporous silica nanoparticles (MSNs) covered with nanovalves such as rotaxanes were used to retain drugs in their pores until gatekeepers were removed by an external stimuli that could be an enzyme. Cyclodextrin (CD)-based molecules can effectively block the pore of MSNs through cleavable intermediate linkages and dissociate to achieve a rapid drug release [129].

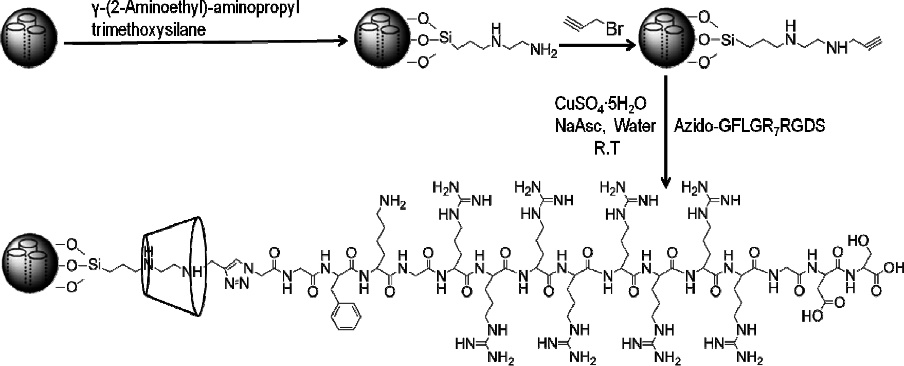

Multifunctional peptides, α-cyclodextrin (α-CD) and an alkosylane tether were employed to get multifunctional rotaxanes on MSNs [130]. The peptide sequence was composed of three functional segments: a cell-penetrating peptide of seven arginines (R7), an enzyme-cleavable peptide of glycine-phenylalanine-lysine-glycine (GFLG) and a tumor-targeting peptide of arginine-glycine-aspartic acid-serine (RGDS) (Figure 13). DOX-loaded MSNs could be specifically loaded on tumor cells through the interaction between RGDS and an integrin receptor overexpressed on these cells; the encapsulated drug could be quickly released through the cleavage of GFLG peptide by cathepsin B, giving rise to an enhanced antitumor activity.

Mesopores of MSNs were end capped with a conjugate of phenylboronic acid (PBA) and serum albumin (HAS), which was immobilized onto MSMs via an intermediate link with phenylalanine-valine-glycine-lysine-isoleucine-glycine (PVGLIG) peptide, which was an appropriate substrate for the MMP-2 enzyme. HSAhas good biocompatibility and plays a sealant function, PBA was selected as a targeting motif since it has a high affinity with sialic acid (SA) that is abnormally produced in tumor cells (e.g. HepG2 cells of a liver tumor). The over-expressed MMP-2 in the tumor microenvironment could break down the intermediate peptide linker, inducing cell apoptosis by the anticancer drug loaded in the MSN (e.g. DOX) [131].

Enzyme-responsive capsules can also be prepared by LbL assembly by taking advantage of the capability of enzymes to degrade the capsule to provide a controlled and sustained release of the encapsulated molecules [132]. Logically, the drug release profile depended on the thickness of the shell (e.g. the number of layers and their individual thickness) and the nature of selected polymers. Natural polymers such as poly(l-lysine) (PLL) and other polypeptides like poly(L-arginine) [133] have been considered. Drugs like the anti-cancer DOX were conjugated to alkyne-functionalized poly(L-glutamic acid) to get degradable capsules by LbL assembly [134].

Effective cancer treatment is nowadays hindered by the multidrug resistance (MDR) to chemotherapeutic agents, which is mainly caused by the overexpression of ATP binding cassette (ABC) transporters (e.g. P-glycoprotein (Pgp)) that facilitates the removal of drugs from the cells causing insensitivity [135]. The use of the microcapsules loaded with either DOX or PTX through alkyne-functionalized poly(L-glutamic acid) and builded by LbL assembly were revealed to be efficient to restore drug sensitivity to the MDR cells, making it possible to bypass Pgp-mediated MDR [136].

8. Light-Responsive Polymers Based on Polypeptides

Photo-responsive chemical groups (e.g. azide, 6 diazo, pyrene and cinnamate) can be attached to a polymer chain in such a way that conformational changes can be triggered by exposure to UV, optical and near-infrared (NIR) electromagnetic radiation [137,138]. The last appears most interesting for tumor targeting since it is less harmful to cells and can penetrate more deeply into tissues [139]. Cinnamic acid is an intermediate metabolite in the biosynthetic pathway of lignin and other biological materials [140] and may experience several photoreactions (e.g. cycloaddition and trans/cis isomerization) that may give rise to photoactive proteins [141].

Many systems are based on amphiphilic block copolymer micelles (BCPs), in which a hydrophobic block has a chromophore pendent group. BCPs can form core-shell micelles or vesicles for encapsulation of hydrophobic and hydrophilic agents, respectively. Under light stimulation, the chromophore groups experience a photoreaction that shifts the hydrophilic/hydrophobic balance toward the dissociation of the micellar aggregates [138]. Basically, photoreaction should increase the polarity of the hydrophobic moiety or induce a conformational change that converted the hydrophobic block into a hydrophilic one. Changes have also been described as reversible through the action of UV (dissociation) and visible light (aggregation) [142]. The great advantage of light-responsive polymers is their great selectivity of the time and the site of release.

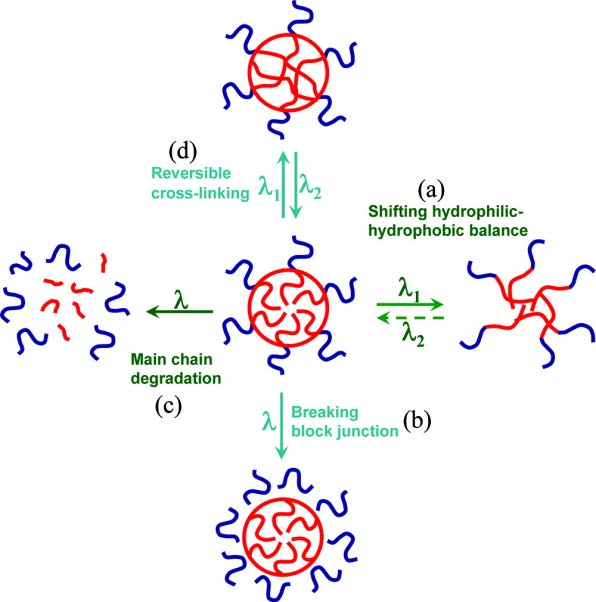

Zhao [143] indicated four possible approaches to get light sensitive BCPs. The most usual (Figure 14a) is based on a photochemical reaction inside the micelle that increases the polarity of the hydrophobic block and leads to the micellar disassembly. The photoreaction can simply cleave the junction between the hydrophobic and the hydrophilic blocs leading again to the disruption of the micelle (Figure 14b). The third approach is based on the presence of several photocleavable units along the hydrophobic block that ensures a photoinduced degradation (Figure 14c). Finally, reversible photo-crosslinking reactions are also being considered as a plausible alternative (Figure 14d).

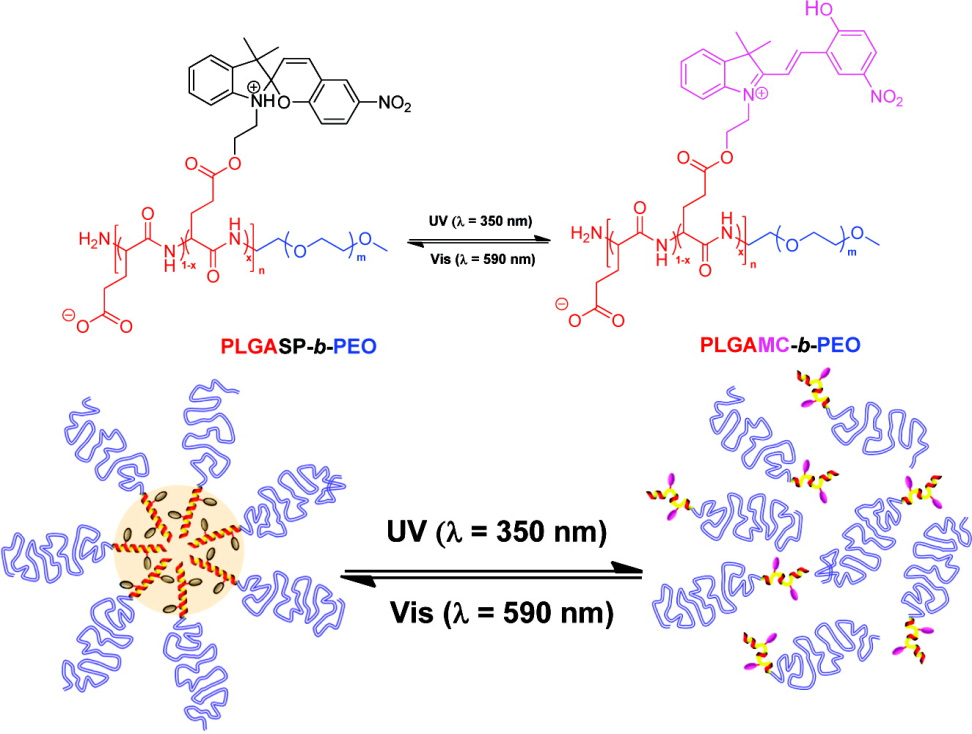

Copolymers constituted by synthetic polypeptides and poly(ethylene oxide) (PEO) are considered an interesting and a versatile platform for the preparation of light-responsive nanocarriers. Thus, poly(L-glutamic acid)-b-PEO shows a reversible micellization/dissolution process in aqueous solutions when spiropyran groups were attached to the glutamic acid units (Figure 15). In fact, UV irradiation at 350 nm caused an isomerization from spyropyran (colorless, nonpolar, hydrophobic and closed form molecule) to merocyanine (coloured, polar, hydrophilic and open form molecule) that could be reverted under exposure to visible light [144].

The biocompatible block copolymer composed of PEO and poly(L-glutamic acid) (PLGA) bearing 6-bromo-7-hydroxycoumarin-4-ylmethyl groups was sensitive to NIR and considered appropriate for light-induced drug delivery (e.g. rifampicin and pacliataxel as antibacterial and anticancer drugs, respectively). Micelles of the copolymer can be disrupted by 794 nm NIR light excitation via two-photonabsorption of the coumarin moiety [145].

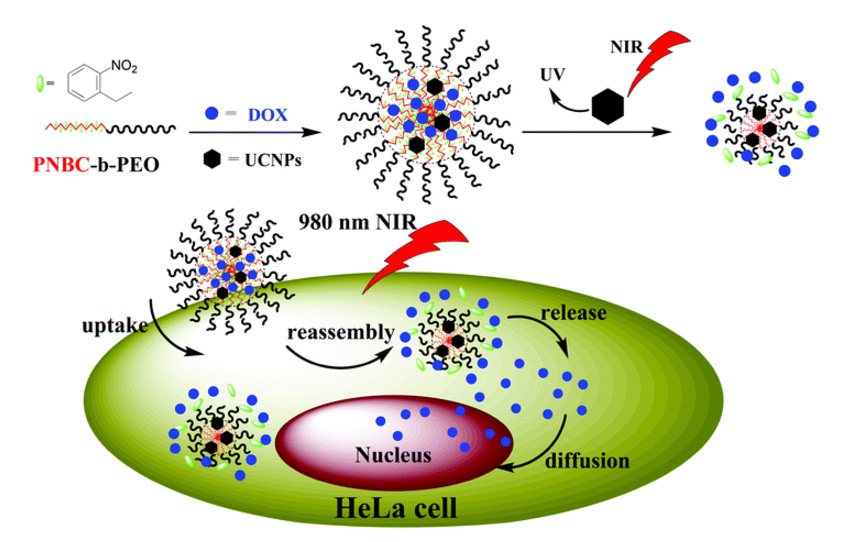

The polypeptide block copolymer poly(S-(o-nitrobenzyl)-L-cysteine)-b-PEO (PNBC-b-PEO) can experience a UV-responsive disassembly-to-reassembly process that leads to a triggered drug release profile [146]. In order to avoid cellular destruction caused by UV light, lanthanide-doped upconversion nanoparticles (UCNPs) were added since they can convert low-energy excitation photons (e.g. NIR) into shorter wavelength emissions (e.g. UV). Thus, novel NIR-responsive polypeptide copolymer upconversion composite nanoparticles of PNBC-b-PEO-UCNPs (Figure 16) have been prepared [147]. This nanocomposite exhibited a fast NIR-sensitivity when irradiated at 980 nm, had an enhanced cytotoxicity and could quickly enter into HeLa cells compared with free drugs as DOX.

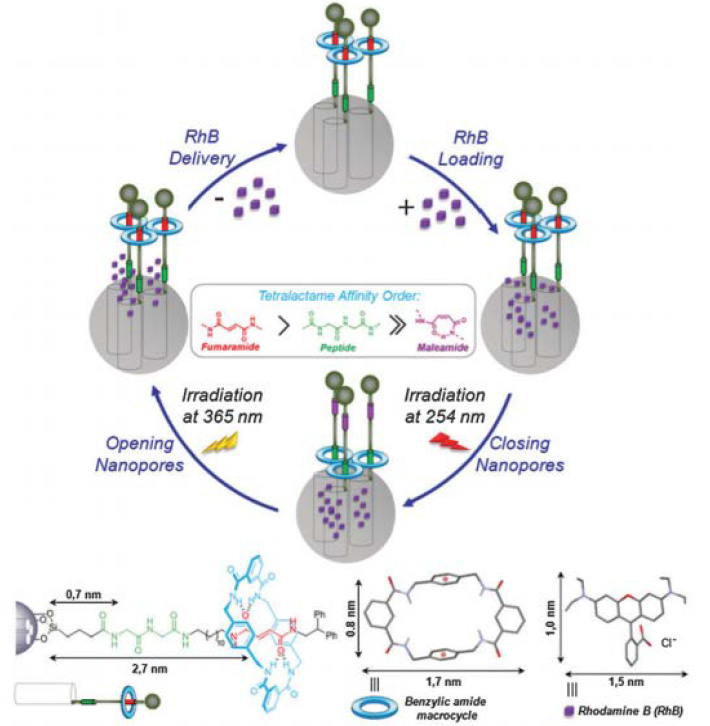

Mesoporous silica nanoparticles with a peptide-based molecular shuttle (rotaxane) as a photocontrollable gatekeeper have been designed as light-operated nanocontainers [148] (Figure 17). Rotaxanes are molecules in which a macrocycle is mechanically locked onto a thread by two bulky stoppers. They have potential to be employed as switchable components for artificial machines [149] that function through mechanical motion at the molecular level to store information [150]. Controlling such motion in the solid state could be used to store information.

The loading and delivery of rhodamine has been successfully undertaken for a system based on the light-induced E/Z isomerization of a fumaramide-based binding site for shuttling a benzylic amide macrocycle along the thread of a bistable [2]rotaxane. The isomerization of the olefin leads to a maleamide derivative with a lower binding affinity with the macrocycle and its translocation towards the peptide-based binding site (e.g. a glycine-L-leucine unit) [151]. This movement is reversible depending on the wavelength of the irradiation and causes the closing and opening of a molecular gate on the surface of the silica support and therefore the loading and release of the cargo (Figure 17).

9. Electric-Responsive Polymers Based on Polypeptides

Biomaterials which are able to respond to electrical and biological cues are attractive for multiple biomedical applications by acting as nerve conduits and neural probes. A simple potential switching may, for example, promote or inhibit the adsorption of proteins or bacterial cells [152]. Electrical and biological stimuli can be combined by immobilizing nerve growth factor (NGF) on the surface of an electrically conducting polymer such as polypyrrole (PPy) [153]. Important efforts are focused on the synthesis of hybrids constituted by conducting polymers (CPs) and peptides for the fabrication of appropriate platforms for adhesion and growth of cells in tissue engineering [154,155]. Incorporation of biological molecules designed to render a response from specific cells can allow controlling the interaction between CP and tissues. In this sense, peptide sequences are relevant since they can have specific cell response ligands for cell attachment and growth.

An interesting approach to the design of hybrid materials is the use of peptides bearing chemical groups similar to those of the CP at which they will be joined. This arrangement appears more efficient than those based on non-covalent formulations. Thus, poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) (PEDOT) as an example of CP has been successfully conjugated with a syntheticamino acidbearing3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene [156]. The resulting hybrid material preserved the electrical conductivity, electroactivity, electrochemical stability, and specific capacitance while the behavior as bioactive substrate was improved with respect to selected CP.

Electroactive polymer-peptide conjugates have also been synthesized by combining the conducting poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) and an RGD-based peptide in which Gly has been replaced by an amino acid bearing a 3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene ring in the side chain [157]. The electrochemical activity and the bioactivity (e.g. cell adhesion) of the conjugates was enhanced with respect to the conducting polymer alone.

Pulsatile drug delivery systems (PDDS) provide spatial and temporal release with increased patient compliance. An electrical signal can be employed for PDDS [158,159], which can be easily generated by small, portable equipment. This signal can be controlled easily, long cycles are possible and a remote control outside the body can be achieved when an appropriate sensor is also used.

Wu et al. [160] reported an interesting PDDS system controlled by electrical stimulation for the treatment of the Alzheimer’s disease (Figure 18).

Graphene-mesoporous silica nanohybrids (GSNs) were employed as the dopant confined in conducting polypyrrole films. These nanoparticles GSNs provided a high drug loading capacity for both hydrophobic and hydrophilic drugs and gave rise to a sustainable release profile. Specifically, clioquinol was selected as a chelating agent to disrupt amyloid aggregates. Additionally, electrochemical stimulation was an efficient therapeutic treatment for stimulating neurite and axon extension for nerve regeneration.

Conducting polymer nanoparticles (CPNs) with the ability for selective collagen binding were prepared by nanoprecipitation using a collagen mimetic peptide (CMP)-polymer hybrid as the stabilizing amphiphile. Size of particles (between 15 and 40 nm) was controlled upon modifying the amphiphile concentration. Coated nanoparticles were efficient to either probe collagen strands or enable sensitive fluorescence imaging of collagen in fixed tissue sections [161].

10. Multiresponsive Polymers Based on Polypeptides

Dual and multi-responsive polymers have also been designed in order to give combined responses to external stimuli either simultaneously or in a sequential way. Therefore, different polymeric systems sensitive to pH/temperature, pH/redox, pH/magnetic field, temperature/redox, temperature/magnetic field have been proposed [162]. In this way, a great control over drug release can be achieved and specifically a better anti-cancer activity could be attained [Figure 19]. Different multi-responsive systems have been recently reviewed by Cheng et al. [162], some of them based on polypeptides.

Thus, triblock copolymers PEG-b-poly(l-aspartic acid/mercaptoethylamine)-b-poly(l-aspartic acid/2-(diisopropylamine) were prepared from silica nanoparticles that incorporate ethylamine and were employed to get crosslinked micelles loaded with DOX and sensitive to both pH and redox potential [163].

Nanoparticles sensitive to both pH and magnetic field were prepared from silica nanoparticles that incorporated Fe3O4 and were grafted with mPEG-poly(l-asparagine). Imidazole groups (pKa∼6.0) were linked to the side chains of the amino acid units to impart pH sensitive properties. In this way, a core-shell-corona trilayer magnetic nanoparticle (MN) was obtained in aqueous solution. The mPEG outer corona layer essential to prolong lifetime of nanoparticles in blood circulation [164].

A functional polymer with a clear demarcation between hydrophilic and hydrophobic segments through reductive disulfide bonds has been prepared to display both pH and redox sensitive properties [165]. Polyethylene glycol and cyclo(Arg-Gly-Asp-D-Phe-Cys) (cRGD) peptide were conjugated to poly(2-(pyridine-2-yldisulfanyl)ethyl acrylate) through thiol-disulfide exchange reaction. The peptide sequence was selected to enhance selective targeting to cancer cells overexpressing integrins. Nanoparticles loaded with DOX were stable in physiological conditions, while a fast DOX release was triggered by acidic pH and redox potential giving rise to a two-phase release kinetics that could mimic the clinic dosing pattern (i.e. an initial high loading dose and then a low maintenance dose).

A last example of the interest to create multi-responsive polymers corresponds to development of polyplexes for gene delivery and treatment of atherosclerotic lesions [166]. In this case, the abnormal cell behavior is reflected by the overproduction of reactive oxygen species (ROS). PEGylated, oligoproline peptide-derived nanocarriers have been obtained to improve pDNA transfection into pathological cells with high ROS concentration due to the inflammatory activation. Specifically, the cysteine-(proline)5-lysine peptide was chosen as an ROS degradable block. The synthesized polyplexes demonstrated also an ideal pH responsiveness for endosomal escape.

11. Conclusion

Smart polymer systems based on polypeptides offer a great potential in the biomedical field and especially for therapeutic cancer treatment since an appropriate targeting to malign cells can be achieved as well as a selective release at tumor sites. Great advances in the design of polymers and nanoparticles could provide adequate targeting ligands and a selective response to external stimuli.

Anionic or cationic peptides can be joined with hydrophilic blocks to render amphiphilic molecules that can be self-assembled into micelles, nanoparticles and vesicles depending on the final composition and the pH of the medium.

Polymers susceptible to temperature also have promising and real applications in the treatment of tumors, being developed specific systems based on peptides to respond to a local and mild hyperthermia (37-42 ºC).

Peptides having disulfide crosslinks are ideal to get redox responsive polymers taking profit of the high concentration of glutathione in cancer cell and its reductive character.

Magnetic agents can also be incorporated into polypeptide based nanoparticles providing composite materials for targeting drug delivery, magnetic hyperthermia and tissue engineering and also as contrast agents in magnetic resonance imaging.

A different drug release mechanism can be achieved by means of peptides designed to mimic the substrates of enzymes that are overexpressed in cancer tissues. Great progresses are also being achieved by attaching photo-responsive chemical groups that allows triggering conformational changes by exposition to UV radiation. Original systems like mesoporous silica nanoparticles having a peptide-based molecular shuttle as a photocontrollable gatekeeper are being proposed as light-operated nanocontainers. Efforts are also focused to create nanoparticles able to convert low energy photons in UV radiation to promote conformational changes.

Hybrid materials constituted by a conducting polymer and a peptide are considered in order to get pulsatile drug delivery systems able to provide spatial and temporal release with an increased patient compliance.

Logically, the development of dual (e.g. pH/temperature, pH/redox, pH/magnetic field, temperature/redox, temperature/magnetic field) and multiresponsive polymers opens a wide range of applications in the biomedical field, which are not yet fully explored and even are unsuspected. In any case, advances in such systems must obviously provide a relevant benefit to humanity.

Acknowledgments

Authors are in debt to supports from MINECO and FEDER (MAT2015-69547-R) and the Generalitat de Catalunya (2014SGR188).

Conflict of Interest

Authors declare that there is not conflict of interest.

DownLoad:

DownLoad: