1.

Introduction

The ordinary differential equation

is well known as the logistic equation in both ecology and mathematical biology, where r and K are positive constants that stand for the intrinsic growth rate and the carrying capacity, respectively. It follows from Eq (1.1) that the U′(t)/U(t) is a linear growth function of the density U(t). However, Smith[1] concluded that the Eq (1.1) does not have practical significance for a food-limited population under the influence of environmental toxicants. Based on the above fact, Smith established a new growth function in [1]. Besides, Smith also pointed out that a food-limited population requires food for both preservation and growth in its growth. For another thing, when the specie is mature, food is needed for preservation only. Therefore, the modified system is as follows

where r, K and α are positive constants, and rα is the replacement of mass in the population at K.

In [2], Wan et al. considered a single population food-limited system with time delay:

they studied existence of Hopf bifurcations and global existence of the periodic solutions at the positive equilibrium. Eq (1.3) has been discussed in the literature by numerous scholars, they mainly concluded global attractivity of positive constant equilibrium and oscillatory behaviour of solutions of Eq (1.3) [3,4]. Su et al.[5] considered the conditions of steady state bifurcation and existence of Hopf bifurcation of food-limited population system under the dirichlet boundary condition for Eq (1.1). In addition, Gourley et al.[6] investigated the global stability, boundedness and bifurcations phenomenon of Eq (1.2) with nonlocal delay. About more interesting conclusions for food-limited system, we refer to the literature [7,8,9,10,11].

However, in real world, the interaction of prey and predator is one of the basic relations in biology and ecology. The dynamical analysis of the predator-prey system is a hot issue in biomathematics all the time, an important reason is that compared with single population system, multi-population system can exhibit complex dynamical behavior. The well-known predator-prey system has been widely studied by many ecologists and mathematicians. The authors in [12,13] developed food-limited population system to prey-predator system of functional response. Moreover, the reproduction of predator after preying upon prey is not instantaneous, but is mediated by some reaction time delay τ for gestation. Compared with the predator-prey system without delay, the time-delay predator system is more ecological significance. The delay has an effect on population dynamics and induces very rich dynamical phenomenon, see [14,15,16,17,18,19,20]. Here, we will take ratio-dependent functional response into consideration, i.e., the characteristic of consumption of prey is mUVβU+γV. The predation and reproduction of predator are not simultaneous. Taking into account the delay, the reproduction of predator from consuming the prey is nU(t−τ)VβU(t−τ)+γV. Hence, the prey-predator system with ratio-dependent and food-limited as follows

where the variables U(t) and V(t) denote the densities of the prey and predator at time t, respectively. r, K, m, n and e are all positive constants that stand for the intrinsic growth rate of the prey, the carrying capacity of the prey species, predate rate of prey, converation rate from prey, and mortality rate of predator, positive constants β and γ are half saturation constant, τ(>0) is a time delay which occurs in the predator response term and represents a gestation time of the predators.

In fact, biological resources in the predator-prey system are most likely to be harvested for economic benefit, human need to develop biological resources and capture some biological species, such as in fishery, forestry and wildlife management[21]. Hence, the demand of sustainable development for suitable resources is felt in different region of human activities to maintenance the stability of the ecosystem. We know that harvesting in population has a significant impact on the dynamic behavior of species, because of the reduction of food in the space. There are some basic types of harvesting being considering in the literature, see [21,22,23,24,25,26]. Nevertheless, a great number of mathematicians have a strong interest in nonlinear harvesting, because Michaelis-Menten type harvesting is more realistic in biology and ecology[22]. Inspired by the above discussion, system (1.4) with nonlinear prey harvesting transforms into the following system

where q, E, m1, m2 are also positive constants. q is the catchability coefficient, E is the effort applied to harvest prey species, m1 and m2 are suitable constants. Fang gave some sufficient conditions of the existence of positive periodic solutions for a food-limited predator-prey system with harvesting effect in [24,25].

In nature, the populations all require food, space and spouse and so on for survival and reproduction. When the larger the density of population is, the higher require on the environment. The shortage of food and the change in space always limit its survival and development. Naturally, the populations change position or have a diffusion to search better environment. We assume that the populations are in an isolate patch and ignore the impact of migration, including immigration and emigration. Individuals tend to migrate towards regions with lower population densities for each population. To take spatial effects into consideration, reaction diffusion system become more and more important, see [12,13,23,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35]. In this paper, we study the following reaction diffusion system:

where Ω⊂Rn(n≥1) is a bounded region and it has smooth boundary ∂Ω. D1 and D2, respectively, denote the diffusion coefficients of the prey and predator, and they are positive constants. Δ denotes the Laplacian operator in Rn, ϑ is outer normal vector of a boundary ∂Ω.

To simplify the system (1.6), we use the following nondimensionalization:

Then rewrite the system (1.6) as follows:

Denote F(u,v)=u(1−u)d+u−suvau+bv−huρ+u, G(u,v)=cu(t−τ)vau(t−τ)+bv−δv, Λ={a,b,c,d,h,s,ρ,δ}. In this paper, the domain of system is confined to Ω=[0,lπ], we define a real-valued Hilbert space

The corresponding complexification is XC:={x1+ix2:x1,x2∈X}, with the complex-valued L2 inner product

for Ui=(ui,vi)∈XC(i=1,2).

The rest of the paper is arranged as follows. In section 2, the existence and priori bound of solution of the system (1.7) are considered. In section 3, the existence of nonnegative constant steady state solutions is investigated. In section 4, the stability of the nonnegative constant steady state solutions of system (1.7) and the conditions of Hopf bifurcation and Turing instability are discussed by stability analysis and bifurcation theory. In section 5, we give the detailed formulas to determine the direction of Hopf bifurcation and the stability of the bifurcating periodic solutions by the normal form theory and center manifold theorem for PFDEs. In section 6, some numerical simulations are carried out to illustrate the correctness of the theoretical results. Finally, some conclusions and discussions are given.

2.

Existence of solution and priori estimate

In this section, we establish the existence of solution of system (1.7) and a priori estimate of the solution. Firstly, we have

where f(u,v)=−u2+(1−ρ−h)u+ρ−dh. Define m_=1−ρ−h−√(1−ρ−h)2−4(dh−ρ)2, ¯m=1−ρ−h+√(1−ρ−h)2−4(dh−ρ)2.

Theorem 2.1. The following statements are true for system (1.7).

(1) Given any initial condition u0(x)≥0, v0(x)≥0, and u0(x)≢0, v0(x)≢0, then system (1.7) has a unique solution (u(t,x),v(t,x)), such that u(t,x)>0 and v(t,x)>0 for t∈(0,∞) and x∈Ω.

(2) If one of three conditions holds

(2a) (1−ρ−h)2<4(dh−ρ) and dh−ρ>0,

(2b) (1−ρ−h)2≥4(dh−ρ), 1−ρ−h<0 and dh>ρ,

(2c) (1−ρ−h)2≥4(dh−ρ), 1−ρ−h>0, dh>ρ and u0(x)<m_,

then (u(t,x),v(t,x)) tend to (0,0) uniformly as t→∞.

(3) For any solution (u(x,t),v(x,t)) of system (1.7), if one of two conditions holds

(3a) dh<ρ,

(3b) (1−ρ−h)2≥4(dh−ρ), 1−ρ−h>0 and dh>ρ,

then

where C2=c4dsδ|Ω|+c¯ms|Ω|.

(4) If d1=d2 and τ=0, then lim supt→∞max¯Ωv(t,x)≤c4dsδ+c¯ms for any x∈Ω.

Proof. (1) Obviously, F(u,v) and G(u,v) are mixed quasi-monotone in set ¯R2+={(u,v)|u≥0,v≥0}. According to the definition of upper and lower solutions in [16], denoted (u_,v_)=(0,0) and (¯u,¯v)=(˜u,˜v), where (˜u,˜v) is the unique solution of the following system,

where ¯u0=sup¯Ωu0(t,x), ¯v0=sup¯Ωv0(t,x), t∈[−τ,0]. Consider that

and 0≤u0(t,x)≤¯u0, 0≤v0(t,x)≤¯v0. Then (¯u,¯v) and (u_,v_) are the upper-solution and lower-solution of system (1.7). So we have that any solution of system (1.7) is nonnegative and exists on [0,∞), it exhibits that system (1.7) has a global solution (u(t,x),v(t,x)) satisfying

Then u(t,x)>0,v(t,x)>0 by the strong maximum principle for all t>0 and x∈¯Ω.

(2) We are able to get from the first equation of system (1.7) that

If (1−ρ−h)2<4(dh−ρ), we can obtain that (1−u)(ρ+u)−dh−hu<0 for all u>0, it leads to ˜u→0 as t→∞. Suppose (1−ρ−h)2≥4(dh−ρ) and dh>ρ hold, if either 1−ρ−h<0 or 1−ρ−h>0 and u0(x)<m_, then ˜u→0 as t→∞. Therefore u(t,x)→0 uniformly on ¯Ω as t→∞. Similarly, we have that v(t,x)→0 uniformly on ¯Ω as t→∞ from the second equation of system (1.7).

(3) Consider any of conditions (3a)−(3b), then it follows from the first equation of system (1.7) that

according to Eq (2.3) and comparison principle, we can get that

There exists a t1, such that u(t,x)≤¯m+ε for t≥t1 and x∈¯Ω, where ε is a arbitrarily small positive constant.

To the estimate v(t,x). Denote ¯U(t)=∫Ωu(t,x)dx and ¯V(t)=∫Ωv(t,x)dx. By the Neumann boundary condition, we obtain

Then

It follows from u(t,x)≤¯m+ε that ¯U(t)≤(¯m+ε)|Ω| for any t≥t1, we have

where C1=c4d|Ω|+cδ(¯m+ε)|Ω|.

By the comparison principle and Eq (2.4), we obtain

Hence,

(4) When d1=d2 and τ=0, let S(t,x)=cu(t,x)+sv(t,x). By Eq (1.7), we have

From Eq (2.5), we get

for t>0 and x∈Ω.

Consider

The solution Z(t,x) satisfies limt→∞Z(t,x)=c4dδ+c¯m by using [36,Theorem 2.4.6], then the comparison principle displays that

This completes the proof of Theorem 2.1.

3.

The nonnegative constant steady states of system (1.7)

In reality, we are interested in all the nonnegative steady state solution. Next, we give the conditions of existence of nonnegative constant steady state solutions for system (1.7).

Proposition 3.1. (1) The singularity E0=(0,0) always exists.

(2) If (h+ρ−1)2=4(dh−ρ) and h+ρ−1<0 hold, then semi-trivial steady state E10=(1−h−ρ2,0)(the boundary equilibrium) exists.

(3) If ρ>dh holds, then semi-trivial steady state E30=(¯m,0) exists.

(4) If (h+ρ−1)2>4(dh−ρ), h+ρ−1<0 and ρ<dh hold, then semi-trivial steady state E20=(m_,0) and E30=(¯m,0) (the boundary equilibrium) exist.

In ecology, we concentrate on the existence of the positive constant steady state solutions. System (1.7) has a positive constant steady state E∗=(u∗,v∗), where v∗ satisfies v∗=(c−aδ)u∗bδ under c−aδ>0 and u∗ satisfies the following quadratic equation

with A0=(c−aδ)sbc+1, A1=(c−aδ)(d+ρ)sbc+ρ+h−1, A2=(c−aδ)dρsbc+dh−ρ.

For the distribution of roots of Eq (3.1), we are able to get the following results about the existence of a positive constant steady state solution.

Lemma 3.1. Suppose c−aδ>0 holds, then the following statements are true.

(1) If A1<0,A21−4A0A2>0 and A2>0, then Eq (3.1) has two positive roots u±∗=−A1±√A21−4A0A22A0.

(2) If A1<0,A21−4A0A2=0, then Eq (3.1) has a unique positive root u0∗=−A12A0.

(3) If A2<0, then Eq (3.1) has a unique positive root u∗=u+∗.

By Lemma 3.1, the following Proposition is existing.

Proposition 3.2. Suppose c−aδ>0 holds, then the following statements are true.

(1) When A1<0,A21−4A0A2>0 and A2>0, the system (1.7) has two positive steady states E+∗=(u+∗,v+∗) and E−∗=(u−∗,v−∗), where v±∗=(c−aδ)u±∗bδ.

(2) When A1<0,A21−4A0A2=0, E+∗ and E−∗ merge, denoted by E0∗=(u0∗,v0∗).

(3) When A2<0, the system (1.7) has a unique positive steady state E∗=(u∗,v∗).

4.

Stability and bifurcation

In this section, we consider the stability of nonnegative steady state and the conditions of Hopf bifurcation and Turing bifurcation. In [37], we know that Laplacian operator −Δ exists the eigenvalue n2l2(n∈N0:=N∪{0}) under the homogeneous Neumann boundary condition, let φ1n=(βn0)T, φ2n=(0βn)T be eigenfunctions on X, where βn(x)=cos(nlx). The linearization of system (1.7) at a constant steady state ˆE=(ˆu,ˆv) can be represented by

where D=diag(d1,d2), J1=(a11a120a22), J2=(00a210), and

The characteristic equation of system (1.7) is

where I stands for 2×2 identity matrix and Dn=−n2l2diag(d1,d2), n∈N0. Then we obtain

with Mn=(d1+d2)n2l2−a11−a22, Nn=d1d2n4l4−(a11d2+a22d1)n2l2+a11a22, Q=−a12a21.

Firstly, we discuss the stability of the singularity E0=(0,0) and the semi-trivial steady state solutions Ei0(i=1,2,3).

Theorem 4.1. (1) The singularity E0=(0,0) is always locally asymptotically stable if dh>ρ, and unstable if dh<ρ.

(2) Suppose (h+ρ−1)2=4(dh−ρ) and h+ρ−1<0 hold, the semi-trivial steady state E10 is always locally asymptotically stable if c−aδ<0 and (dh+dρ−1)(ρ+√dh−ρ)2+h(d+√dh−ρ)2<0, and unstable if c−aδ>0 or d(ρ+h)>1.

(3) Suppose dh<ρ holds, the semi-trivial steady state E30 is locally asymptotically stable if c−aδ<0 and d−2d¯m−1(d+¯m)2+h(ρ+¯m)2<0, and unstable if c−aδ>0 or ¯m<d−12d, d>1.

(4) Suppose (h+ρ−1)2>4(dh−ρ), h+ρ−1<0 and ρ<dh hold,

(i) the semi-trivial steady state E20 is locally asymptotically stable if c−aδ<0 and d−2dm_−1(d+m_)2+h(ρ+m_)2<0, and unstable if c−aδ>0 or m_<d−12d, d>1;

(ii) the semi-trivial steady state E30 is locally asymptotically stable if c−aδ<0 and d−2d¯m−1(d+¯m)2+h(ρ+¯m)2<0, and unstable if c−aδ>0 or ¯m<d−12d, d>1.

Proof. (1) By Eq (4.1), the corresponding characteristic equation of system (1.7) at E0=(0,0) is

clearly, we have

Therefore, if dh>ρ, λ1 and λ2 have negative real part for all n∈N0, so we get that the equilibrium E0=(0,0) is locally asymptotically stable. On the contrary, if dh<ρ, there exists n=0 that λ1>0, then E0=(0,0) is unstable.

(2) At E10, then J1=(a11−sa0c−aδa), J2=(0000), we are able to get J(n,E10)=(a11−sa0c−aδa), where a11=1−ρ−h2(dρ+dh−1(d+√dh−ρ)2+h(ρ+√dh−ρ)2).

For n≥0, the corresponding characteristic equation of system (1.7) at E10 is

where Mn=(d1+d2)n2l2−a11−c−aδa, Nn=d1d2n4l4−(a11d2+c−aδad1)n2l2+a11c−aδa.

By c−aδ<0 and (dh+dρ−1)(ρ+√dh−ρ)2+h(d+√dh−ρ)2<0, we have Nn>0 and Mn>0 for n≥0, which implies E10 is locally asymptotically stable. In a similar method, by c−aδ>0 or d(ρ+h)>1, it is obvious that J(n,E10) has at least one eigenvalue with a positive real part for n=0, which implies E10 is unstable.

(3) Suppose dh<ρ holds, then semi-trivial steady state E30=(¯m,0) exists by Proposition 3.1. We can have J(n,E30)=(a11−sa0c−aδa), where a11=¯m(d−2d¯m−1(d+¯m)2+h(ρ+¯m)2).By c−aδ<0 and d−2d¯m−1(d+¯m)2+h(ρ+¯m)2<0, we have Nn>0 and Mn>0 for n≥0, which means E30 is locally asymptotically stable. Similarity, by c−aδ>0 or ¯m<d−12d and d>1, it is obvious that J(n,E30) has at least one eigenvalue with a positive real part for n=0, which implies E30 is unstable.

(4) The proof of (4) is similar to (3), so we omit it.

This completes the proof.

Theorem 4.2. If (ρ+h−1)2<4(dh−ρ) holds, then E0=(0,0) is globally asymptotically stable in ¯R2+ for system (1.7) with τ=0.

Proof. Define the following Lyapunov functional

Then

It follows from (ρ+h−1)2<4(dh−ρ) that for all u≥0,

Furthermore, ddtV(u,v)≤0, ddtV(u,v)=0 if and only if (u,v)=(0,0). Then we can have that the trivial steady state E0=(0,0) is globally asymptotically stable for system (1.7) with τ=0.

This completes the proof.

Next, we investigate the stability of positive constant steady state E∗. In the following discussion, we always assume

(H1):c−aδ>0,(c−aδ)dρsbc+dh−ρ<0(i.e.,A2<0).

For the convenience of discussion, we make the following hypothesis:

(H2):a11+a22<0;

(H3):a11a22−a12a21>0;

(H4):a11d2+a22d1<0,

where a11=d−u2∗−2du2∗(d+u∗)2−bsv2∗(au∗+bv∗)2−hρ(ρ+u∗)2, a12=−asu2∗(au∗+bv∗)2, a21=bcv2∗(au∗+bv∗)2, a22=acu2∗(au∗+bv∗)2−δ.

Theorem 4.3. Assume that (H1)∼(H4) hold. Then the unique positive constant steady state E∗=(u∗,v∗) of system (1.7) with τ=0 is locally asymptotically stable, that is, system (1.7) has no stationary pattern under these hypothesis.

Proof. If (H1) holds, the system (1.7) has a unique positive constant steady state E∗. When τ=0, the corresponding characteristic equation of system (1.7) at E∗ is

Obviously,

It follows easily from (H2)∼(H4) that all roots of Eq (4.2) have negative real parts. Hence, by Routh−Hurwitz stability criterion, the unique positive constant steady state E∗ is locally asymptotically stable for τ=0 when hypothesis (H2)∼(H4) hold.

This completes the proof.

According to the work by Turing[38], positive constant steady state E∗ is Turing instability, implying that E∗ is asymptotically stable for non-spatial system (1.7) but is unstable for spatial system (1.7) with τ=0. So we make the following hypothesis:

(H5):a11d2+a22d1>0;

(H6):a11d2+a22d1−2√d1d2(a11a22−a12a21)>0.

Theorem 4.4. If τ=0, then diffusion-driven instability (i.e., Turing instability) occurs for the system (1.7) if (H1)∼(H3) and (H5)∼(H6) hold, that is, system (1.7) has stationary pattern under these hypothesis.

Proof. We know that the positive equilibrium E∗=(u∗,v∗) is stable for the non-spatial system (1.7), and is unstable with respect to the constant steady state solution of the spatial system (1.7) with τ=0. The stability of non-spatial system (1.7) is guaranteed if hypothesis (H2)∼(H3) hold. When τ=0, the corresponding characteristic equation of system (1.7) at E∗ is Eq (4.2). Obviously, for spatial system (1.7), it follows from (H5)∼(H6) that if there is a n∈N0 such that Nn+Q<0 for 0<k1<n<k2, which implies that Eq.(4.2) has a eigenvalue with positive real part, it is shown that the positive constant steady state E∗ is unstable for spatial system (1.7), that is, the diffusion-driven instability occurs.

This completes the proof.

Now, by regarding τ as the bifurcation parameter, we investigate the stability and the Hopf bifurcation near the unique positive constant steady state E∗. Assume that iω(ω>0) is a root of Eq (4.1), ω satisfies the following equation

which implies that

By Eq (4.4), adding the squared terms for both equations yields

where

Let S=ω2, we have

For the following discussion, we make some assumption:

(H7):a11a22+a12a21>0,

(H8):a11a22+a12a21<0.

Theorem 4.5. Assume that (H1)∼(H4) and (H7) hold. Then all roots of Eq (4.1) have negative real parts for all τ≥0. Furthermore, the unique positive constant steady state E∗=(u∗,v∗) of system (1.7) is locally asymptotically stable for all τ≥0.

Proof. From Eq (4.6), we have Pn>0. By (H1)∼(H4) and Theorem 4.3, we have Nn+Q>0. If (H7) holds, then

for all τ≥0, which implies that Eq (4.8) has no positive roots, according to [19,Lemma 2.3], therefore the characteristic Eq (4.1) has no purely imaginary roots. Combined with Theorem 4.3, we are able to obtain that all roots of Eq (4.1) have negative real parts for any τ≥0.

This completes the proof.

Lemma 4.1. ([39])Let f(y) be a positive C1 function for y>0, and let d>0,β≥0 be constants. Further, let T∈[T,∞) and ω∈C2,1(Ω×(T,∞))∩C1,0(Ω×[T,∞)) be a positive function.

(i) If ω satisfies

and the constant α>0, the

(ii) If ω satisfies

and the constant α≤0, the

Theorem 4.6. Suppose that the conditions of Theorem 4.5 are satisfied. Furthermore, assume that d>ρ, ρ−dh−dρsb>0 hold. Then the unique positive constant steady state E∗=(u∗,v∗) of system (1.7) is globally asymptotically stable.

Proof. By the strong maximum principle of parabolic equations, for any nonnegative initial values (u0(x),v0(x))≢(0,0), we have u(t,x)>0,v(t,x)>0 for all t>0 and x∈¯Ω.

From the first equation of system (1.7), we get

By Lemma 4.1, we obtain

for any given ε>0, there exists t1>0 such that for any t>t1, u(t,x)≤¯u1+ε.

Then from the second equation of system (1.7), we have

By Lemma 4.1 again and the any ε, we obtain that

for t>t1+τ, there exists t2>t1 such that for any t>t2, v(t,x)≤¯v1+ε.

On the other hand, from the first equation of system (1.7), we have

where B(u,¯v1+ε)=(1−u)(au+b(¯v1+ε))(ρ+u)−s(¯v1+ε)(d+u)(ρ+u)−h(d+u)(au+b(¯v1+ε)).

Here, let u(y) be solution of B(u,y)=0. If d>ρ,ρ−dh−dρsb>0 hold, we get B(−ρ,¯v1+ε)<0, B(−d,¯v1+ε)<0, B(0,¯v1+ε)>0, B(1,¯v1+ε)<0, then B(u,¯v1+ε)=0 exists unique positive root u(¯v1+ε).

It follows from Lemma 4.1 that

for t>t2 and any ε>0, there exists t3>t2 such that for any t>t3, u(t,x)≥u_1−ε.

Then from the second equation of system (1.7), we have

By Lemma 4.1 again and the any ε, we obtain

for t>t3+τ and any ε>0, there exists t4>t3 such that for any t>t4, v(t,x)≥v_1−ε.

Meanwhile, the first equation of system (1.7) can be written as

Similarly, by d>ρ,ρ−dh−dρsb>0, we know that B(u,v_1−ε)=0 has a unique positive root u(v_1−ε) and

for t>t4 and any ε>0, there exists t5>t4 such that for any t>t5, u(t,x)≤¯u2+ε.

It is easily known that

and u_1,¯u1,v_1,¯v1 satisfy the following inequalities

The Eq (4.9) reveals that (¯u1,¯v1) and (u_1,v_1) are coupled upper and lower solutions of system (1.7) by Definition 2.1 in [16].

Moreover, we derive the following inequality:

It is easy to display that there exists a positive constant Ki(i=1,2) such that the following Lipschitz condition holds

So we can define sequences (¯un,¯vn) and (u_n,v_n) as follows

where n=1,2,⋅⋅⋅, (¯u0,¯v0)=(¯u1,¯v1) and (u_0,v_0)=(u_1,v_1).

It is easy to deduce that the sequences (¯un,¯vn) and (u_n,v_n) satisfy the following a series of inequalities

and that the limits

exist and satisfy the following equations

From the conditions of Theorem 4.6, we get that the system (1.7) has a unique positive constant steady state E∗=(u∗,v∗), therefore it follows from Eq (4.10) that ¯u=u_ and ¯v=v_. It is well known [36,Theorem 2.4.6] that the solution (u(t,x),v(t,x)) of system (1.7) satisfies

uniformly for x∈¯Ω. By Theorem 4.5, if (H1)∼(H4) and (H7) hold, then the unique positive constant steady state E∗=(u∗,v∗) is locally asymptotically stable. Hence, the unique positive constant steady state E∗=(u∗,v∗) is globally asymptotically stable.

Denote

and

Therefore, we have the following Lemma.

Lemma 3. Assume (H1)∼(H4) and (H8) hold, then Eq (4.1) has a pair of purely imaginary roots ±iωn(0≤n≤N∗) at τjn, where

Clearly, we know that τj+1n>τjn, therefore the following Lemma exhibits that we get a complete ordering of the Hopf bifurcation parameters τjn.

Lemma 4. Assume (H1)∼(H4) and (H8) hold, then

for j∈N0.

Proof. From Eq (4.11), we have

Obviously, by Eq (4.6) and Eq (4.7), we know that M2n−2Nn is increasing in n and Q2−N2n is decreasing in n. Hence we have that

And notice that Nn is strictly increasing in n∈[0,N∗], then we deduce that ω2n−NnQ is strictly decreasing in n∈[0,N∗]. Hence, τjn=1ωnarccosω2n−NnQ+2jπωn is strictly decreasing in n∈[0,N∗], that is, Eq (4.12) is correct for any n∈[0,N∗].

This completes the proof.

It follows from Eq (4.12) we obtain

Let λ(τ)=p(τ)±iq(τ) be the pair of root of Eq (4.1) near τ=τjn satisfies p(τjn)=0 and q(τjn)=ωn. Then we have the following transversality condition.

Lemma 4.4. For n∈{0,1,2,⋅⋅⋅,N∗} and j∈N0,

Proof. Differentiating two sides of Eq (4.1) with respect to τ, we get

Therefore,

Thus, by Eq (4.3) and Eq (4.4), we have

This completes the proof.

According to above analysis, and the qualitative theory of partial functional differential equations, we obtain the following results on the stability and Hopf bifurcation.

Theorem 4.7. Assume (H1)∼(H4) and (H8) hold, then the following statements valid

(1) The unique positive constant steady state E∗=(u∗,v∗) of system (1.7) is locally asymptotically stable for τ∈[0,τ00) and always unstable when τ>τ00.

(2) System (1.7) undergoes Hopf bifurcations near the unique positive constant steady state E∗=(u∗,v∗) at τjn for n∈{0,1,2,⋅⋅⋅,N∗},j∈N0. If n=0, the bifurcating periodic solutions are all spatially homogeneous. Otherwise, these bifurcating periodic solutions are spatially inhomogeneous.

5.

Stability and direction of Hopf bifurcation

In this section, we investigate the stability of the bifurcating periodic solution and direction of Hopf bifurcation by applying center manifold theorem and normal form theory of PFDEs[40]. For convenience, for fixed j∈N0, 0≤n≤N∗, we denote τ∗=τjn.

Firstly, we let ˜u(t,x)=u(τt,x)−u∗, ˜v(t,x)=v(τt,x)−v∗ and drop the tilde. Then system (1.7) can be transformed into:

Let μ=τ−τ∗, μ∈R, U=(u(t,⋅)v(t,⋅))T. After the system (5.1) can be rewritten in an abstract form in the phase space C=C([−1,0],X) as

where D=diag(d1,d2), L(τ∗)(ϕ) and F(ϕ,μ) are defined by

with f(ϕ,μ)=(τ∗+μ)(F1(ϕ,μ)F2(ϕ,μ))T and

F1(ϕ,μ)=(ϕ1(0)+u∗)(1−ϕ1(0)−u∗)d+(ϕ1(0)+u∗)−s(ϕ1(0)+u∗)(ϕ2(0)+v∗)a(ϕ1(0)+u∗)+b(ϕ2(0)+v∗)−h(ϕ1(0)+u∗)ρ+(ϕ1(0)+u∗)−a11ϕ1(0)−a12ϕ2(0),

F2(ϕ,μ)=c(ϕ1(−1)+u∗)(ϕ2(0)+v∗)a(ϕ1(−1)+u∗)+b(ϕ2(0)+v∗)−δ(ϕ2(0)+v∗)−a21ϕ1(−1)−a22ϕ2(0),

for (ϕ1ϕ2)T∈C.

Linearizing Eq (5.2) at (0,0), we can obtain the following equation

About the discussion of characteristic roots in section 4, we get that the characteristic equation of Eq (5.3) has a pair of simple purely imaginary eigenvalues Λn={iωnτ∗,−iωnτ∗} and consider the following functional differential equation

According to the Riesz representation theorem, there exists a 2×2 matrix function η(θ,τ,n)(−1≤θ≤0), whose elements are of bounded variation functions such that

for ϕ∈C.

Actually, we choose

Let us define C∗=C([0,1],R2∗), where R2∗ is the two-dimensional vector space of row vectors, A(τ∗) denotes the infinitesimal generator of the strongly continuous semigroup induced by the solution of Eq (5.4) and A∗ with domain dense in C∗ and is the formal adjoint of A∗ under the bilinear form

for ϕ∈C, ψ∈C∗.

Let P and P∗ be the center subspace, that is, the generalized eigenspace of A(τ∗) and A∗ associated with Λn. A(τ∗) has a pair of simple purely imaginary eigenvalues ±iωnτ∗, and A∗ has also a pair of simple purely imaginary eigenvalues ±iωnτ∗.

Let q(θ)=(1M)Teiωnτ∗θ(−1≤θ≤0), q∗(s)=(1N)e−iωnτ∗s(0≤s≤1) be the eigenfunctions of A(τ∗) and A∗ corresponds to iωnτ∗ and −iωnτ∗, respectively. By simple calculation, we have

Denote Φ=(Φ1Φ2) and Ψ∗=(Ψ∗1Ψ∗2)T by

for θ∈(−1,0), and

for s∈(0,1).

We define

and construct a new basis Ψ for P∗ by Ψ=(Ψ1Ψ2)T=(Ψ∗,Φ)−1Ψ∗, then (Ψ,Φ)=I2.

We denote fn=(φ1nφ2n). Let α⋅fn be defined by

According to [40], the center subspace of linear Eq (5.4) is given by PCNC, where PCNC=Φ(Ψ,⟨ϕ,fn⟩)⋅fn,ϕ∈C, and C=PCNC⨁PsC, PsC denotes the complement subspace of PCNC in C.

Eq (5.2) can be rewritten the following an abstract ordinary differential equation

where

By the decomposition of C, the solutions of system (5.2) are

where

and

Following the theory in [40] and [41], the center subspace of the linear system of system (5.3) with μ=0 is given by PCNC where

Then the solutions of system (5.2) are

where W(z,¯z)=h(z+¯z2,i(z−¯z)2,0),z=x1−ix2. According to [40], z satisfies the following equation

where

Let

and Ψ1(0)−iΨ2(0)=(χ1χ2). By Eq (5.6) and Eq (5.9), then we get

and

where

b20=−2d(2du∗+u∗+1)(d+u∗)3+2absv2∗(au∗+bv∗)3+2hρ(ρ+u∗)2, b11=−2absu∗v∗(au∗+bv∗)3, b02=2absu∗(au∗+bv∗)3,

b30=8d2u∗+4du∗−4d3−2d2+6d(d+u∗)4−6a2bsv2∗(au∗+bv∗)4−6hρ(ρ+u∗)4, b21=4a2bsu∗v∗−2ab2sv2∗(au∗+bv∗)4,

b12=4ab2su∗v∗−2a2bsu2∗(au∗+bv∗)4, b03=−6ab2su∗(au∗+bv∗)4, c20=−2abcv2∗(au∗+bv∗)3, c11=2abcu∗v∗(au∗+bv∗)3,

c02=−2abcu2∗(au∗+bv∗)3, c30=6a2bcv2∗(au∗+bv∗)4, c21=2ab2cv2∗−4a2bcu∗v∗(au∗+bv∗)4, c12=2a2bcu2∗−4ab2cu∗v∗(au∗+bv∗)4,

c03=6ab2cu3∗(au∗+bv∗)4.

Therefore

with Γ=1lπ∫lπ0β3n(x)dx, γ1=1lπ∫lπ0(ζ1β2n(x)+ζ2β4n(x))dx,γ2=1lπ∫lπ0(ν1β2n(x)+ν2β4n(x))dx, and

ζ20=14(b20+M(2b11+Mb02)), ζ11=14(b20+(M+¯M)b11+M¯Mb02),

ζ1=W(1)20(0)(b20+¯Mb112)+W(1)11(0)(b20+Mb11)+W(2)20(0)(b11+¯Mb022)

+W(2)11(0)(b11+Mb02),

ζ2=b308+(2M+¯M)b218+(M2+2M¯M)b128+M2¯Mb038,

ν20=14(c20e−2iωnτ∗+M(2c11e−iωnτ∗+Mc02)),

ν11=14(c20+(Meiωnτ∗+¯Me−iωnτ∗)c11+M¯Mc02),

ν1=W(1)20(−1)(c20eiωnτ∗+¯Mc112)+W(1)11(−1)(c20e−iωnτ∗+Mc11)

+W(2)20(0)(c11eiωnτ∗+¯Mc022)+W(2)11(0)(c11e−iωnτ∗+Mc02),

ν2=c30e−iωnτ∗8+(2M+¯Me−2iωnτ∗)c218+(M2eiωnτ∗+2M¯Me−iωnτ∗)c128+M2¯Mc038.

Consider that

then we deduce

Combine with Eq (5.8), Eq (5.10) and Eq (5.11), we have g20=g11=g02=0,n=1,2,3,⋅⋅⋅. If n=0, g20=(ζ20χ1+ν20χ2)τ∗,g11=(ζ11χ1+ν11χ2)τ∗,g02=(¯ζ20χ1+¯ν20χ2)τ∗, and for n∈N0, g21=(γ1χ1+γ2χ2)τ∗.

By Eq (5.5), we obtain

Moreover, W(z,¯z) satisfies

where

Hence, it follows from Eq (5.8), (5.10) and Eq (5.12–5.14) that

Since A(τ∗) has only two eigenvalues ±iωnτ∗, Eq (5.15) has only a unique solution Wij.

Next, we need to calculate Hij(θ),θ∈[−1,0]. We get that for −1≤θ<0,

Hence, by comparing the coefficients, and notice that

we have

By the definition of A(τ∗) and Eq (5.15), we have

That is

Utilizing the definition of A(τ∗) and combining Eq (5.15) and the above discussions, it follows that

Thus, we can compute the following formulas which determine the direction and stability of bifurcating periodic orbits:

In fact, μ2 determines the directions of the Hopf bifurcation, β2 determines the stability of the bifurcating periodic solutions, T2 determines the period of bifurcating periodic solutions. Moreover, by [41], we have the following results.

Theorem 5.1. For any critical value τjn, the following statements valid

(1) If μ2>0 (resp.<0), then the Hopf bifurcation is forward (resp. backward), that is, the bifurcating periodic solutions exist for τ>τjn (resp. τ<τjn).

(2) If β2<0 (resp.>0), then the bifurcating periodic solutions are orbitally asymptotically stable (resp. unstable).

(3) If T2>0 (resp.<0), then the period increases (resp. decreases).

6.

Numerical simulations

In this section, we perform some results of the numerical simulations to illustrate our mathematical findings in the previous sections. All of our numerical simulations employ the Neumann boundary conditions.

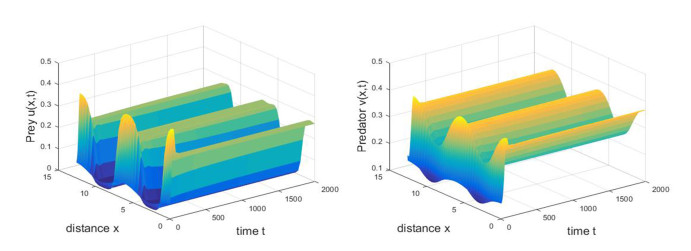

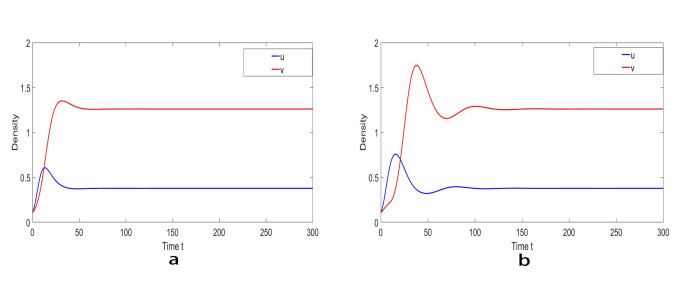

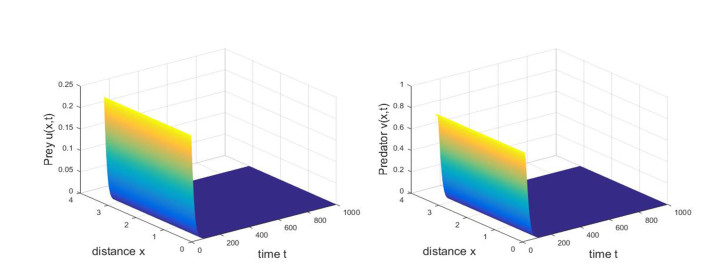

6.1. Global stability

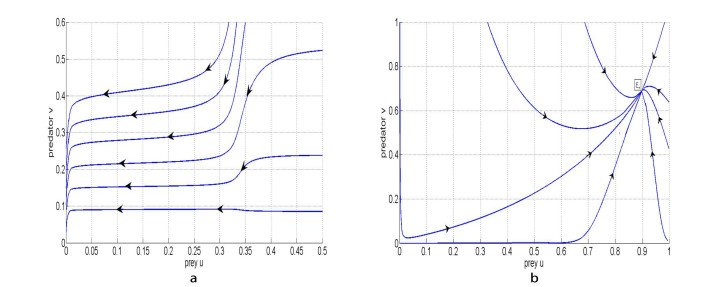

To portray the global stability of trivial steady state E0 and the positive constant steady state E∗, let a=1.35,b=0.01,c=1.353,d=0.5676,δ=1,h=0.28,ρ=0.045,s=0.001, by simple calculation, we are able to obtain (ρ+h−1)2<4(dh−ρ). It follows from Theorem 4.2 that E0 is globally asymptotically stable. It can be seen Figure 1a. Moreover, denote a=0.2,b=1.5,c=1.35,d=0.5676,δ=1,h=0.06,ρ=0.045,s=0.01, then the unique positive constant steady state E∗=(0.8984,0.6894) is globally asymptotically stable by Theorem 4.6. As shown in Figure 1b.

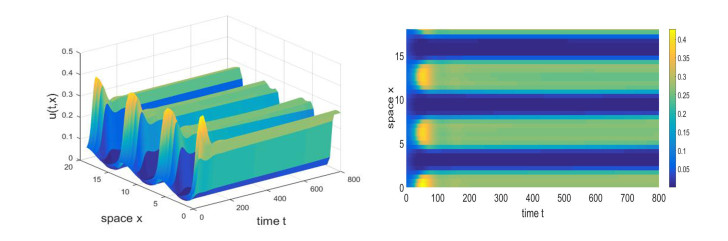

6.2. Turing instability

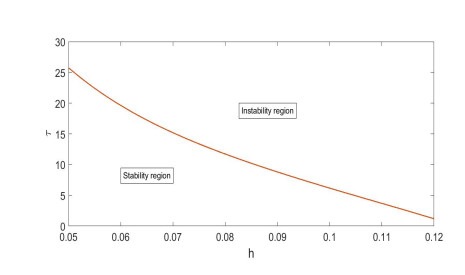

We consider the Turing instability with respect to the unique positive constant steady state E∗ of system (1.7) with τ=0. Let a=1.2,b=0.5,c=0.4,d=1.8,δ=0.15,h=0.161,ρ=0.5,s=0.2,d1=0.005,d2=0.5 and l=4. By simple calculation, we obtain that system (1.7) has a unique positive steady state E∗=(0.0527,0.1547). It follows from Theorem 4.4 that assumption (H1)∼(H3) and (H5)∼(H6) are satisfied, that is, the positive steady state E∗ for the ODE system is stable. However, for the PDE system, the positive steady state E∗ becomes unstable, and system (1.7) has a stable nonconstant steady state solution, which means that a Turing instability occurs. This is shown in Figure 2. It portrays that the population is irregularly distributed in space. We also observe that the system (1.7) has a stationary spatial pattern, that is shown in Figure 3. Moreover, choose d1=0.01, we are able to observe that under the effect of diffusion coefficients of d2, system (1.7) portrays different spatial patterns that can be periodic, stationary, as shown in Figure 4.

6.3. Delay induced Hopf bifurcation in system (1.7)

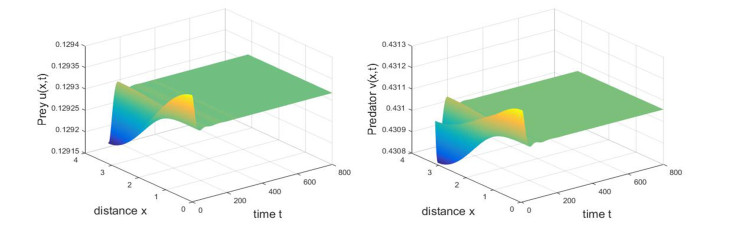

Firstly, we consider that the unique positive constant steady state E∗ of system (1.7) is locally asymptotically stable for all τ≥0. Let a=1,b=0.5,c=0.4,d=2,δ=0.15,h=0.01,ρ=0.5,s=0.2,d1=0.01,d2=0.02. By calculation, the positive constant steady state E∗=(0.3783,1.2611), the conditions (H1)∼(H4) and (H7) are satisfied. It follows from Theorem 4.5 that the unique positive constant steady state E∗ of system (1.7) is locally asymptotically stable for all τ≥0 in Figure 5.

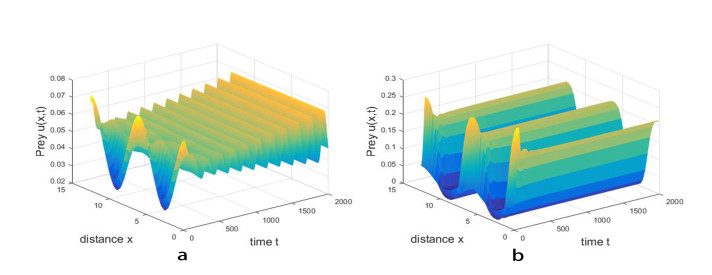

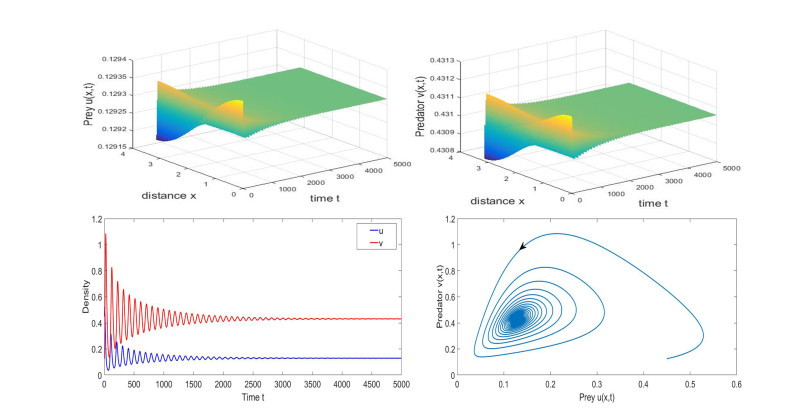

Consider system (1.7) with the parameters a=1,b=0.5,c=0.4,d=2,δ=0.15,h=0.1,ρ=0.5,s=0.2,d1=0.01,d2=0.02 and l=1. Calculation shows that system (1.7) has a unique positive constant steady state E∗=(0.1293,0.4311). Hypothesis (H1)∼(H4) and (H8) satisfy for n=0, by calculation we have ω0=0.0652. It follows from Theorem 4.7 that homogeneous Hopf bifurcations occur at τj0≈6.1868+96.3679j for j∈N0. We use the forward Euler method to find numerical solutions to system (1.7) with τ=0,5.85,6.20, respectively. From Theorem 4.3, the unique positive constant steady state E∗=(0.1293,0.4311) of system (1.7) with τ=0 is locally asymptotically stable, it can be seen from Figure 6.

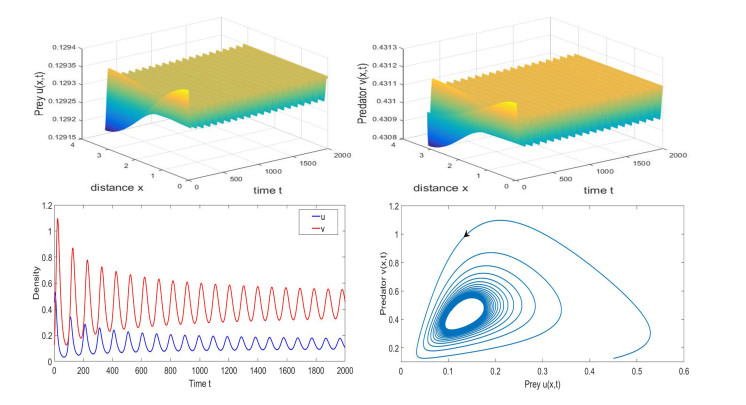

As shown in Figure 7 and 8, we observe sustained oscillations when delay τ crosses the critical value τ00≈6.1868. We have λ′(τ00)≈0.0035−0.0014i by Lemma 4.4. From Theorem 4.7, we know that if τ∈[0,τ00), then the equilibrium E∗=(0.1293,0.4311) is locally asymptotically stable. This is shown in Figure 7. And we conclude that the equilibrium E∗=(0.1293,0.4311) loses its stability and Hopf bifurcation occurs when τ crosses the critical value τ00. By calculation and Eq (5.16), we get C1(0)=−0.5076−1.4071i,μ2≈145.0286>0,β2≈−1.0152<0,T2≈3.9916>0.

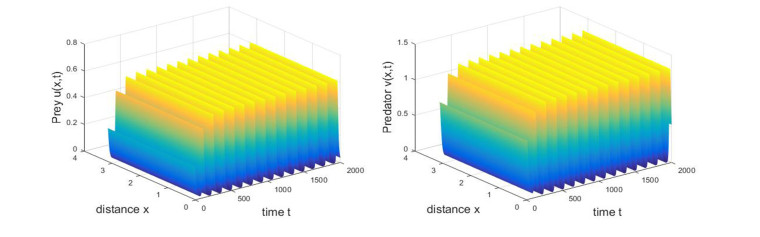

Hence, it follows from Theorem 5.1 that the direction of the bifurcation is forward, and the bifurcating period solutions are locally asymptotically stable. Moreover, the period of bifurcating periodic solutions increases. This is shown in Figure 8. If τ is increasing crosses the critical value τ01≈10.0462, a spatially inhomogeneous periodic solution occurs near the positive equilibrium E∗=(0.1293,0.4311). However, the bifurcating periodic solution bifurcating from the critical value τ01 must be unstable on the whole phase space since the characteristic equation always has roots with positive real parts for τ>τ00≈6.1868. This is shown in Figure 9. Besides, as τ increases further, with the same initial values, the solution of system (1.7) converges to (0,0), which implies that the increasing delay may cause the prey and predator to go extinct. As shown in Figure 10.

6.4. The effect of nonlinear harvesting

Considering the effect of nonlinear harvesting, we denote the parameters be the same as section 6.3 and h vary in [0.05,0.12]. The stability and instability regions of the unique positive constant steady state E∗ for system (1.7) is depicted by mapping the nonlinear harvesting to the critical value of the delay τ in Figure 11. We observe that the nonlinear harvesting effect parameter h increases from 0.05 and 0.12, the Hopf bifurcation is occurred for lower critical values of τ. Meanwhile, we observe that the harvesting effect parameter h has a significant effect on the stability of ecosystem.

7.

Conclusions and discussions

In this paper, we focused on a delayed diffusive predator-prey system with food-limited and nonlinear harvesting effect. Firstly, in order to prove the global stability of the solution, we gave the existence of solution and priori bound. Meanwhile, we also derived the conditions of stability of the nonnegative constant steady state solution. Moreover, the global stability of the trivial and positive constant steady state is investigated. The conditions of Turing instability and Hopf bifurcation are obtained for system (1.7), respecitvely. For the positive constant steady state solution, it is demonstrated that Hopf bifurcation can be occurred when bifurcation parameter τ increases beyond a critical value. We derived the detailed formulas to determine the properties of Hopf bifurcation.

For the system (1.7), it follows from Theorem 4.2 and Theorem 4.6 that the trivial steady state E0 and the positive constant steady state E∗ are globally asymptotically stable under the certain conditions (Figure 1), respectively. From an ecological point of view, due to the food-limited in the natural environment, intraspecific competition in prey population increases, so nonlinear prey harvesting is taken into consideration. Increasing the harvesting effect parameter h properly can decrease the density of prey population so that relieve the pressure of intraspecific competition and the system becomes stable under the certain conditions. However, if h crosses a certain value, the density of prey population begins decreasing and may even become extinct (Figures 10 and 11). The diffusion induces the occurrence of Turing instability for the positive steady state E∗, which means that system (1.7) has a stable nonconstant steady state solution (Figures 2 and 3). Our results also reveal the fact that delay can induce very complex dynamics phenomenon, and a positive constant steady state E∗ is depicted to be locally asymptotically stable when the parameter τ is less than the critical value τ∗ (Figure 7), and a stable periodic solutions will bifurcate from the constant steady state E∗ (Figure 8), when the delay τ increase and it crosses through the critical value τ∗, which means that a stable and spatially homogeneous periodic solutions will occur at the critical value of delay τ∗, when the delay τ continues to increase to a certain value, spatially inhomogeneous periodic solution bifurcates from the positive constant steady state E∗ for system (1.7) (Figure 9). When the delay τ is larger, the solution of system (1.7) tends to (0,0), that is, the population becomes extinct eventually (Figure 10).

From the biological point of view, it is clear that delay, nonlinear harvesting and diffusion effect have a significant impact on the stability for ecosystem.

However, there exists many problems will need to be investigated for system (1.7). Firstly, the selection results of Turing patterns are obtained by weakly nonlinear analysis[29,30]. Secondly, the diffusion of the population is random and homogeneous in this paper, actually, individuals often perform a nonlocal diffusion or heterogeneous diffusion in the real world. Finally, spatial memory and cognition of animals has drawn much attention in the mathematical modeling of animal movement (i.e., memory-based diffusion)[42]. These problems will be investigated in the future.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude to the referees for their valuable comments and suggestions that led to a truly significant improvement of the manuscript. The work is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (11871475) and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central University of Central South University (2019zzts212).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

DownLoad:

DownLoad: